Today's Friday • 7 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

Tidsoptimist (pronounced tid-sop-tuh-mist) is a word for someone who is a “time optimist.”

The Swedes/Norwegians coined that term to mean a person who believes they have more time than they actually do. That time-optimism is why these people are always late.

- Are you one of those people who are perpetually late to everything?

- Do you often say, “Sorry, I’m late,” hoping that others will move on without taking offense?

Frankly, it’s never an issue if it’s rare. People also understand if you were held up by an emergency.

But they get annoyed when you’re a repeat offender. It sends out this message:

“My time matters more than yours.”

You might not see yourself this way. You might not mean to be rude. But your actions shape how others view you.

5 Highly Practical Tips To Stop Being Always Late

You set your clock ahead 10 minutes. It didn’t work.

You tried three extra alarms. You still ran late.

Some people can’t judge time well. Their brains work differently. The ADHD people understand this well; they struggle with what experts call “time blindness.”

Here are five steps that actually work to break your always-late habit:

Step 1. Track Your Routine.

Start tracking your routine.

Tonight, write down every time you were late today. Include how many minutes.

- Left for work → 30 minutes late

- Met person X → 10 minutes late

- Went to bed → 120 minutes late

- Arrived at a party → 60 minutes late

- Came back from lunch → 15 minutes late

Your times don’t need to be exact. Close estimates work fine.

Write down as many late moments as you can remember. Don’t stress if you only catch 2 or 3 events your first day.

Do this for 7 days straight. It takes about 5 minutes each night. You’ll get better with practice.

Don’t try to fix anything yet. Just write it down. Start the next step only after you complete 7 days of tracking.

Step 2. Sort Your Late Times.

Sort your lateness events by time.

At the end of 7 days on the first step, sort your activities in order of lateness, from the worst to best. Use only the minutes you were late. Don’t consider how much trouble each one caused.

If you were 120 minutes late, that goes first. If you were 15 minutes late, that goes last. Even if the 15-minute delay got you fired.

How to do it? Make 6 groups:

- 120+ minutes → submitting a project to your team

- 90 to 120 minutes → getting to a client meeting

- 60 to 90 minutes → returning a call to your friend

- 30 to 60 minutes → going to bed (most people struggle with this)

- 15 to 30 minutes → reaching your kid’s party

- 15 or fewer minutes → showing up at a work event

Seeing your late times in groups helps your brain understand the pattern.

Don’t worry about exact minutes. Close enough works.

Don’t try to fix anything yet. Just sort.

How long does this take? Give it 2 or 3 days.

On to the next step.

Step 3. Pick Out The Tiniest Devil.

Pick your smallest late time.

Choose the activity where you were late by the fewest minutes. We’ll fix that one first.

Two ground rules here:

- Don’t tell anyone your plan. Talking about goals reduces your drive to complete them.

- Set up reminders throughout each day. Use sticky notes everywhere.

How to fix this late habit? Read the next step.

Step 4. Build A New Ritual.

Replace your old habit with new rituals.

Habits run on autopilot. They happen without thinking.

Rituals need your intention and attention. You have to focus and follow the steps.

Charles Duhigg, the author of The Power of Habit, says,

“Rituals, by contrast, are almost always patterns developed by an external source, and adopted for reasons that might have nothing to do with decision-making.”

Rituals are step-by-step instructions you repeat to reach your goal.

Example: Going to bed on time

Start your ritual 90 minutes before bedtime:

- Turn off all screens and devices.

- Wait 10 minutes, then dim half the lights in your house.

- Do your nighttime routine, like brushing your teeth and counting your blessings.

- Thereafter, within the next 5 minutes, turn off all the lights and go to bed in the dark.

Example: Morning exercise daily

- Keep a pair of your running shoes near your bed, not slippers.

- When you get up, put on your shoes first thing. Use the washroom wearing them.

- Once you wear the shoes, don’t take them off until you have walked or jogged for 20 minutes.

Reward yourself each time you complete your ritual. Even a small reward works, but give yourself that reward. Do this daily.

Repeat your ritual for 6 to 8 weeks. It will become your new habit.

Step 5. Make It Utterly Easy.

Make your behavior change easy.

The best way to start a habit change is to KISS: “Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

Start small. Keep expectations low.

If you’re usually 30 minutes late, don’t try to fix all 30 minutes at once. Start with being 5 minutes earlier.

Five minutes feels too big? Try 2 minutes.

Arrive 2 minutes earlier each day. In five days, you’ll be 10 minutes earlier.

That’s it. Two minutes earlier each day.

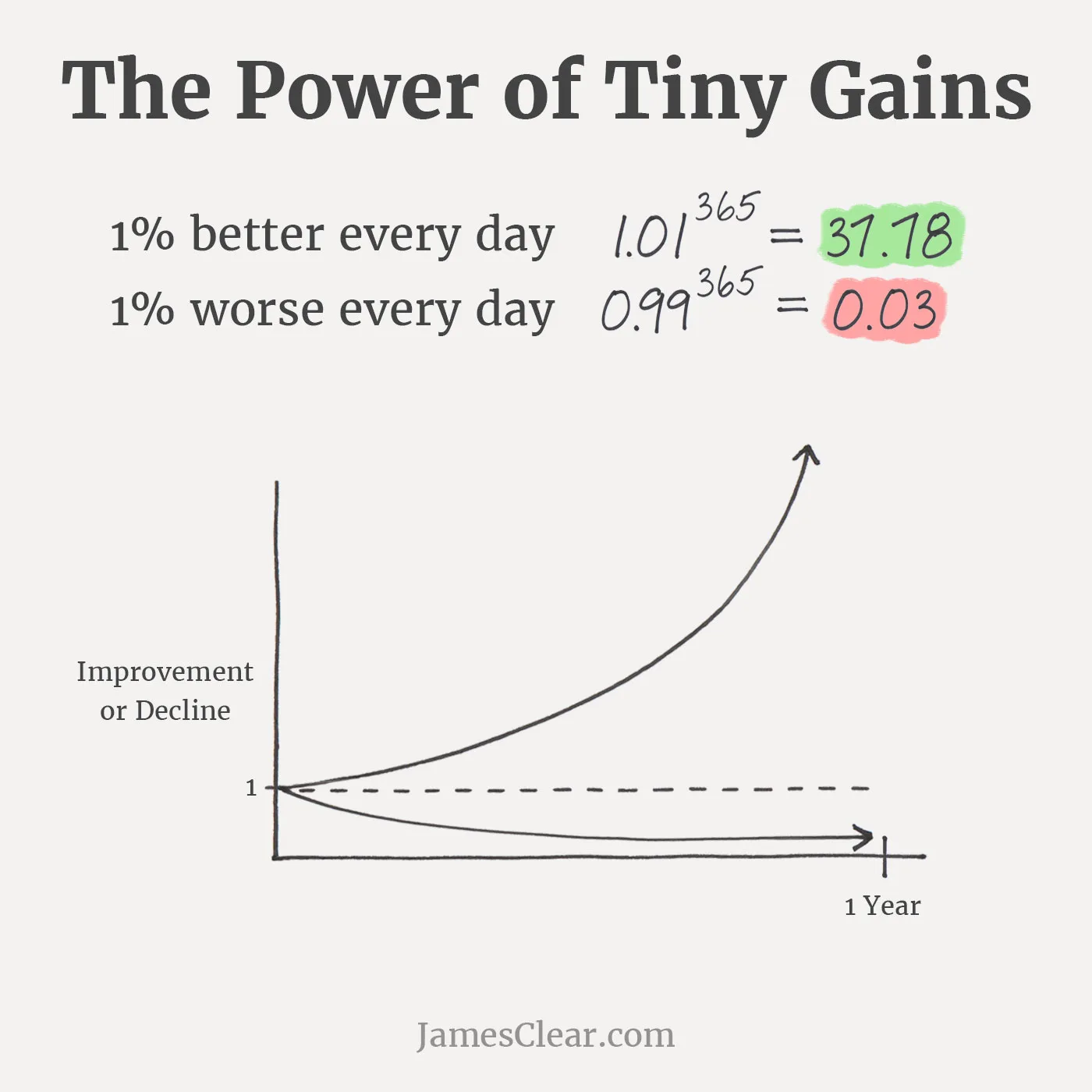

Small changes add up. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, writes:

“If you get one percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you’re done.”

Breaking a habit actually works best when you replace it with a series of small, cohesive rituals.

S.J. Scott explains in Habit Stacking:

You can build a major habit by thinking small enough to get started. Most people don’t need motivation to do one pushup, so it’s easy to get started. And once you get going, you’ll find it’s easy to keep at it.

Changing a habit is never an all-or-nothing process. Don’t straitjacket yourself into a “this time or no other time.” Every little effort counts.

Make The New Habit of Being On Time Stick

The last question: How do you make your new habit of punctuality stick?

The answer: Start a habit chain.

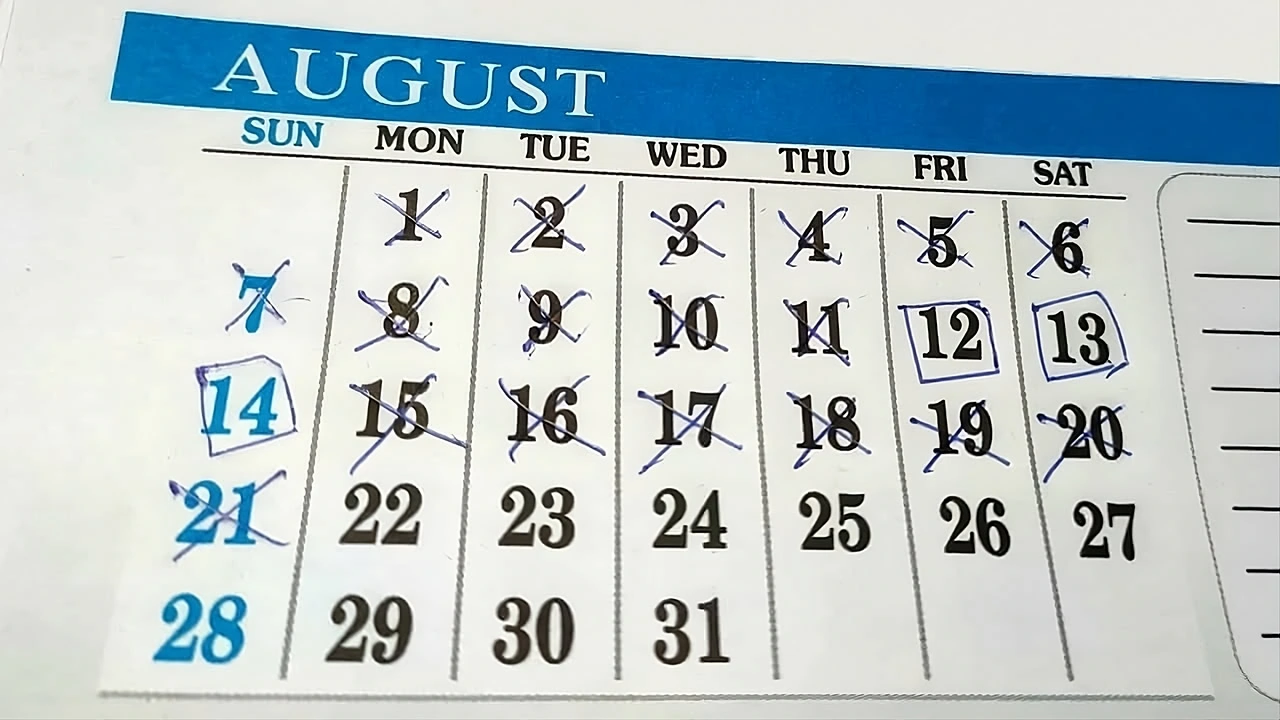

Mark an X on your calendar each day you arrive on time. Don’t break the chain.

Use a habit tracker app. Or use a paper calendar. Both work.

Why Are You Always Late, As Per Psychology?

Most people who are always late have a psychological issue called the planning fallacy.

These people cannot correctly predict how long it will take them to complete a task.

The concept of planning fallacy was first proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. They found such people focus on the most optimistic scenario for the task, instead of using their past experiences to figure out how long similar tasks usually take.

They say, “Oh, it would only take 5 minutes to reach there!” While ignoring that their previous experiences show they were late when they started with 5 minutes on hand.

The word Tidsoptimist, meaning someone who’s a “time optimist,” nails the concept of planning fallacy.

Some other reasons for constantly being late could be low self-control, high anxiety, or perfectionism.

Final Words

Finally, handle yourself with some self-compassion instead of self-criticism.

This is less about a despicable habit that haunts you, and more about a person you want to become as a result of changing that habit.

√ Also Read: 4 Wrongs of Glass-Half-Full People: Optimism Aftershocks

√ Please share it with someone if you found this helpful.

» You deserve happiness! Choosing therapy could be your best decision.

...

• Disclosure: Buying via our links earns us a small commission.