Today's Friday • 13 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

Neuroplasticity is a fascinating Hydra-like trick of the brain.

In Greek mythology, Hydra was a many-headed lake monster that grew two heads when one of its heads was cut.

Our brain cells can do something similar. After trauma from disease or injury, parts of the brain can recast themselves into new roles and handle the new conditions remarkably well. Scientists call this almost magical phenomenon, neuroplasticity.

Let’s start with a basic understanding of neuroplasticity before diving into one of the most fascinating origin stories of brain science research: The Lost Story of Silver Spring Monkeys.

What Is Neuroplasticity?

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to remodel itself by building new nerve connections and taking on new roles. It allows the restructured neurons to compensate for the loss of function caused by brain injury. A neuroplastic brain can adapt to new experiences.

Sometime after brain damage, the nerve fibers (axons) that were broken start sprouting new roots. The intact axons also join in, sprouting new nerve endings. All these new sprigs then seek each other out, create new synapses, and reconnect the broken neurons.

As a result, the new sprouts from the two sources that intertwined lay down a grid of fresh neural pathways to carry out newly assigned missions.

For instance, when one-half of the brain globe (the cerebral hemisphere) gets wrecked, the other side may gradually take control over some of its duties via its extraordinary capacity of neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to form new connections and pathways and change how its circuits are wired.

— Bergland, 2017

A Short History of Neuroplasticity

For several decades, the brain was considered a “non-renewable organ.” That is, the brain cells are of a finite number, and when they die eventually as we age, it’s the end of the line for them. But research proved otherwise.

It was Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the Father of Neuroscience, who first mentioned “neuronal plasticity” in the early 1900s. However, the term “neuroplasticity” was first used in scientific literature by Jerzy Konorski, in 1948. He used it to explain the changes in the nerve structure of our brain cells.

Then came the 1960s, when scientists found the brain could “reorganize” itself after a trauma. Further research discovered that the brain could re-allot large portions of its structure to take up new functions.

And this last discovery in the field of neuroplasticity research is what this story is about.

The Lost Story of Silver Spring Monkeys

How did 17 monkeys help reshape brain science forever?

This is one of the most riveting origin stories of brain science research. Its findings broke and rebuilt our understanding of neuroplasticity.

Sadly, this story of scientific breakthrough was born out of animal cruelty. But it is also a story of redemption, as it gave birth to the biggest society of animal lovers on earth.

Prologue: Sperry And The Brain-Splitting Research

The science of neuroplasticity has its earliest roots in the 1950s, when the American neuropsychologist and neurobiologist Roger W. Sperry started working on split-brains.

For the sake of science, Sperry split apart the two halves of the brains of his lab monkeys and studied their behaviors. His monkeys showed that each half of their brains could still learn new things. But each half did not share its learning with the other half.

Sperry later located some human patients whose brains had been similarly split into two halves to treat their severe epilepsy. He found an identical pattern in these patients. Each of their brain hemispheres had its own world of consciousness and was entirely independent of the other with regard to learning and retention.

Finally, in the winter of 1981, the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, chose Sperry to receive one-half of that year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his two decades of work on split-brains.

Threshold: Taub And The Silver Spring Monkeys

In the summer of the same year, 1981, a 23-year-old boy went to work as an unpaid volunteer at the Institute for Behavioral Research (IBR) in Silver Spring, Maryland. This was a federally funded research facility.

The scientist who ran the IBR lab was Dr. Edward Taub, a psychologist and researcher who loved doing animal experiments. Taub had an impressive record of securing nearly 15 federal grants for eighteen years of his work with monkeys.

The boy apprentice was Alexander Pacheco, son of a doctor. Pacheco, who wanted to be a Catholic priest, found out he had walked into a place that was an animal hell on earth.

Sixteen macaques and one rhesus were kept jammed into small, rusty wire cages roughly 18 inches wide. Many kept their arms hanging out. The air in the lab stank foul with urine, feces, and rotting flesh of these monkeys.

Pacheco soon discovered that in 9 of these seventeen animals, the scientists had cut off the sensory nerves leading from their arms to their brains, a process called deafferentation. This made one or two of their arms go limp and useless.

But Taub, the 50-year-old lead scientist, wanted these monkeys to start using their impaired limbs again. Since the monkeys couldn’t do it, Taub kept devising novel ways to make them move those arms — using mistreatment, hunger, and electric shocks.

In one experiment, the monkeys sat imprisoned inside a dark refrigerator, motionless, until they started receiving electric shocks. The shocks kept coming in bursts and never stopped till they could finally move their crippled arms.

In another, the scientists strapped the monkeys with packing tape at their waists, necks, ankles, and wrists into a chair made of metal pipes. Then, for pain, they latched pliers onto their skin at various places, including their testicles.

When the monkeys couldn’t move their disabled limbs, as further punishment, Taub let them go hungry for days on end.

The repeated trauma and the incessant hunger made these monkeys go so deranged that they gnawed off thirty-nine of their fingers. Dried blood from those fingers caked the cage wires and lab floor.

Pacheco later wrote in an article in Peter Singer’s book In Defense of Animals:

“Several had bitten off their own fingers and had festering stubs, which they extended towards me as I discreetly took a fruit from my pockets. With these pitiful limbs, they searched through the foul mess of their waste pans for something to eat.”

Aghast and appalled, he started secretly photographing these maimed monkeys and logging details of the torturous experiments.

Sometime later, he stole in veterinarians and primatologists as eyewitnesses to tour the lab at night.

Then he went to the police with all his evidence.

On September 11, 1981, in an unprecedented move, the Montgomery County police raided the laboratory and seized the monkeys. They criminally charged Dr. Edward Taub and arrested him for committing animal cruelty and failing to provide adequate veterinary care.

The monkeys were released.

But they had nowhere to go. The county Humane Society, which first agreed to take them in, backtracked on its words.

The respite for the mutilated monkeys came as Lori Lehner, a 23-year-old animal lover who was also a Humane Society member. Lehner took the monkeys in and housed them in the basement of her Rockville home. She pampered them with food, toys, mirrors, and love.

While with Lehner, the monkeys became hooked to daily television shows.

The Blast: Pacheco And The Meteoric Rise of The Saviors

This was the first-ever animal research case against a scientist on American grounds, and later became the first such case to reach the US Supreme Court.

The case launched an animal rights movement that spread like wildfire and drew support from all over the country. Several celebrities and politicians joined the campaign for the release of the monkeys. Finally, the macaques were rescued and spared further research.

Actually, Pacheco was an undercover operative.

Just a year before he walked into the IBR lab, Pacheco had met Washington DC’s first female poundmaster, Ingrid Newkirk, while volunteering at the local dog pound. Together, they had started an animal rights society with about 20 members.

In fact, Pacheco had gone into Taub’s lab as a mole for their act to make public the realities of animal atrocities.

Now, it was through this society that Pacheco and his friends were fighting this high-profile case for the rights of the Silver Spring monkeys. And it was precisely this battle that transformed their fledgling outfit into an internationally known organization.

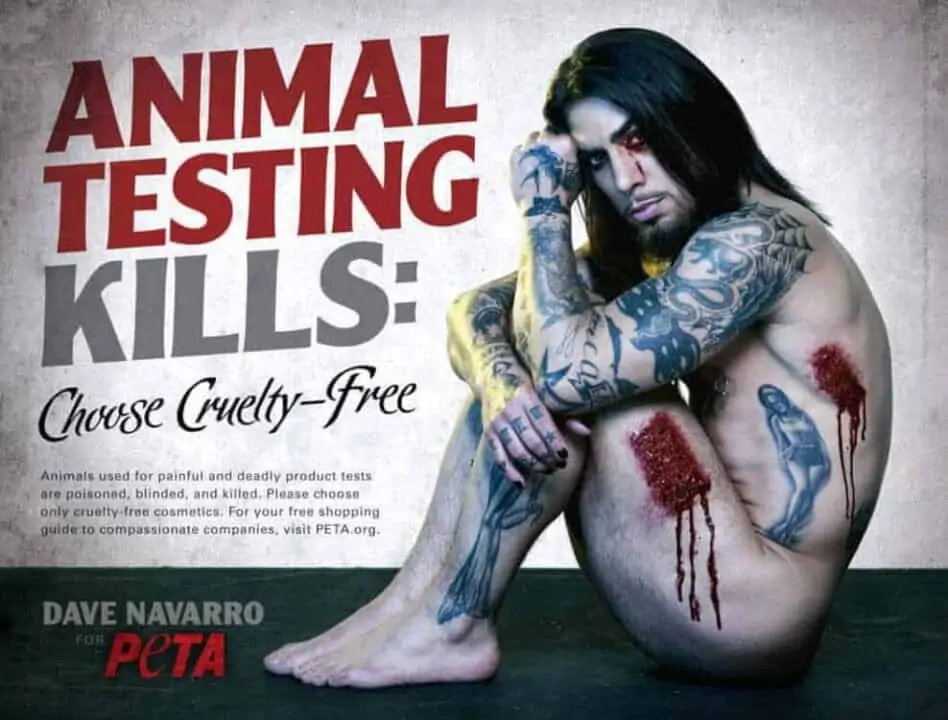

We know them now as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA.

Born in 1980, PETA today is a nonprofit corporation with 300 employees, generating $67 million in annual revenue. It is the world’s largest animal rights organization, with 6.5 million members and supporters from across the world.

Today, anyone can mail an envelope with nothing more than “PETA” written on it from anywhere within the US, and the letter will still reach one of its offices.

Pacheco, who never completed his political science and environmental studies major from George Washington University, served as the chairman of PETA for 20 years before leaving in 2000. Under him, PETA forced many of the world’s largest corporations — General Motors, Exxon, Amway, L’Oréal, Revlon, Mobil Oil, and Benetton — to end various inhumane practices against animals.

As for Taub, he was convicted on six counts of misdemeanors. All six charges, however, were overturned — five during a second trial, by jury, and the sixth on appeal in 1983. He had to pay $3,500 as a fine.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) suspended the remaining $200,000 for Taub’s experiments. But after the courts cleared Taub, the NIH reversed its decision not to fund him.

Did you know that in or around 1982, six senators helped with PETA’s campaign to rescue the horribly abused monkeys by writing to the National Institutes of Health, asking them to release the desperate animals to a sanctuary? One of those senators was Joe Biden of Delaware. About 40+ years ago.

Fragments: Pons And The Last Gift From The Monkeys

The case of the Silver Spring monkeys lasted a decade.

During these 10 years, several of the macaques grew old and lived out their last hours. Finally, in July 1991, the US Supreme Court rejected PETA’s application for the custody of the remaining monkeys.

Days later, to save them from further suffering, the last of the monkeys were humanely put down.

But before that, the neuroscientists from the National Institute for Mental Health approached William Raub, the deputy director of NIH, where the monkeys lived then.

They argued, since the animals were scheduled to be humanely put down, they wanted to examine their brains in one last experiment, for the sake of science. They wanted to see what happened to their brains after the area called the somatosensory cortex stopped receiving any sensation from their limbs.

Raub agreed to the procedure, but on the condition that the scientists finish up within 4 hours, and euthanize the animals before the anesthesia wore off.

So, in 1991, three deafferented monkeys — Augustus, Domition, and Big Boya — were drugged into a deep coma by a group of scientists led by Dr. Tim P. Pons. Then they opened their skulls to place tiny electrodes into the brain areas that normally felt sensations from their paralyzed hands.

The researchers then stimulated points on the face, limbs, and torso of each animal and watched those micro-electrodes pick up signals. When they touched their limbs and trunk, there was no response.

But when they touched their faces, the electrodes recorded bursts of electrical impulses coming from the brain.

This broke the entire field of brain science and stunned neuroscientists everywhere.

The brain region that originally processed sensations from the fingers, hands, and arms of these monkeys had changed its job. After not receiving any signals for some twelve years from those body parts, this brain region was now processing signals from their faces.

This was contrary to everything known to mankind up to that point.

Until then, neuroscientists believed that brain parts that stop receiving signals from a body part would eventually die out. Either the brain did what it was supposed to do, or it shut shop.

But that’s not what had happened in those monkey brains. What had happened was “cortical remapping.”

The non-used brain area in the monkeys had reorganized itself to carry out new functions, to a degree 10 times greater than previously thought.

This was direct evidence of the brain’s massive reorganization capacity — its neuroplasticity (Massive Cortical Reorganization After Sensory Deafferentation).

This ushered in a new era of brain science. Away from the old model, the brain was now an ever-growing and ever-changing organ. The words Pons used to explain the moment:

“It’s absolute dynamite.”

Epilogue: Taub Again, Touched By The Finger of God

Taub originally wanted to find techniques that would help stroke survivors regain the use of their paralyzed limbs.

After the court case, and after receiving dire threats for 5 years, Taub finally received a grant from the University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Working with the grant, Taub developed a new form of physiotherapy for brain-stroke patients with non-functional limbs. Based on neuroplasticity, Taub named it Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy.

The CI therapy or CIMT involves tying up the good arm in a sling or splint and exercising the affected arm intensively for six hours each day for 2 to 3 weeks.

As a result of this, the brain grows new neural pathways so that it can now move the affected wrist and hand.

In simple words, CI therapy changes the brain so the patient can reclaim the use of the affected limb.

Taub carried out several neuroimaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation studies to show that CIMT can produce a massive use-dependent reorganization in the brain cortex.

Taub showed, that with CIMT, the brain increases its area of control over the affected limb.

Over 600 papers have appeared in various publications on the effects of CI therapy. The NIH funded a multi-center clinical trial for stroke rehabilitation by Taub’s therapy. The American Stroke Association endorsed CI therapy for impaired upper limbs of stroke survivors.

In 2015, a team of Cochrane researchers searched the medical literature and identified 42 CIMT studies involving 1453 participants. They concluded:

CIMT appeared to be more effective at improving arm movement than active physiotherapy treatments or no treatment.

In 2003, the Society of Neuroscience named Taub’s CI therapy research as one of the Top 10 Translational Neuroscience Accomplishments of the 20th century.

Final Facts

Animal experimenters have used macaque monkeys to study brains for over 70 years because the functioning parts of their brains resemble much of those of humans.

A 2014 research at Oxford University showed that 11 of the 12 components of the human brain’s vlFC (ventrolateral frontal cortex) had a corresponding area in the macaque brain. A 2017 study found that macaques can evaluate memories just like humans.

Some of those horrifying pictures that Pacheco took are still floating around on the internet. Anyone can find them by Googling ‘Silver Spring Monkeys.’

As of 1981, by one count, 41 Nobel Prizes for Physiology or Medicine had been awarded in this century for research based on animals.

√ Also Read: 6 Signs of Brain Fog That You Can’t Ignore

√ Please share this with someone.

» You deserve happiness! Choosing therapy could be your best decision.

...

• Disclosure: Buying via our links earns us a small commission.