Today's Saturday • 16 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

Vagus, or the “wandering nerve,” is a very long nerve, stretching from the neck to the pelvic area.

It signals the lungs to breathe, the heart to beat, the gut to digest, and the body to “rest” in a stable state of equilibrium, called homeostasis.

Magic happens when you stimulate your vagus nerves. It can turn off your anxiety, lower your blood pressure, slow down your heart rate, and lift your mood.

Doing it is simple, like watching the Supermoon, or using a research-supported technique to engage the vagus nerve in women (the 4th point).

Read on to find science-backed ways to activate your vagus and ease your stress.

How To Stimulate Your Vagus Nerve To Relax & Lift Your Mood

How does it really work? Stimulating the vagus nerves activates the parasympathetic nervous system, which then creates a state of calm and mood-lift.

Here are some ways to do so:

1. Belly Breathing or Diaphragmatic Breathing.

Belly breathing is taking deep breaths in a way that makes the belly rise and fall while the chest remains still. Also known as diaphragmatic breathing or abdominal breathing.

Belly breathing engages the diaphragm (the horizontal partition between our chest and abdomen), which then activates the vagus nerve passing through it.

Here’s how to practice it.

- Lie down on your back on a flat surface, with your knees bent. You may use pillows under your head and your knees for support.

- Place one hand on your upper chest and the other on your belly, just below your rib cage.

- Breathe in slowly through your nose, letting the air in deeply towards the lower belly, so that the hand on your belly rises. Try not to expand your chest, so the hand on your chest stays still.

- Breathe out slowly through pursed lips, squeezing in your abdominal muscles, to release as much air as you can. Your abdomen should cave in, and the hand on your belly should move inward, while the other hand on your chest should stay still.

- Aim to slow your breathing rate down to 5–7 breaths per minute. (Normal respiration rate is 18–20 breaths/minute.)

Just 5–10 minutes of belly breathing can help lift your mood and cut off your anxiety. Doing it regularly keeps you calmer and keeps you from getting triggered.

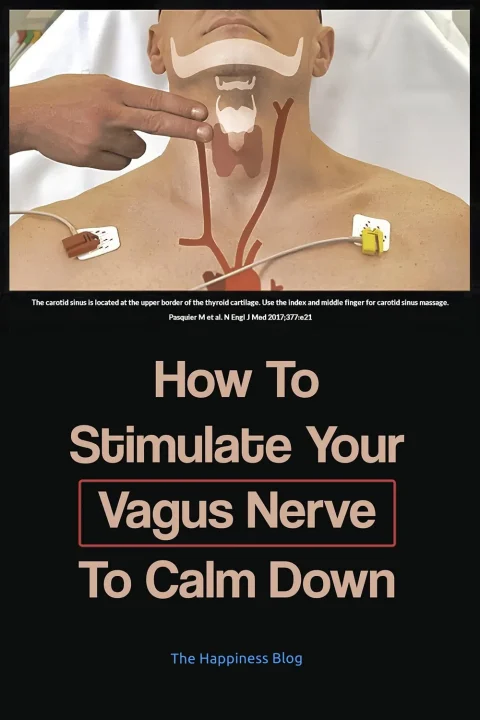

2. Carotid Sinus (Vagus Nerve) Massage.

Carotid Sinus Massage (CSM), or Vagus Nerve Massage, is massaging the carotid sinus to slow down the heart rate and lower our blood pressure.

- The carotid sinuses, or “carotid bulbs,” are small bundles of nerve endings sitting next to the carotid arteries in our neck.

- We have two carotid sinuses, one on each side of the neck, placed roughly below the angle of the jaw, right where each carotid artery forks out into two branches.

- The carotid sinus has chemical and pressure receptors that tell the brain to maintain a controlled supply of blood to the brain, the heart, and the muscles.

Carotid massage is applying finger pressure in longitudinal strokes to the carotid sinus, usually the area of the maximum carotid artery pulsation.

How To Do Carotid Sinus Massage:

- Lie down on your back in a comfortable position.

- Turn your head gently to the side, away from the carotid sinus you want to massage. For example, if you wish to massage the right carotid sinus, turn your head to the left.

- Using your index and middle fingers, lightly feel the side of your neck until you can feel the carotid pulse. This is located just below the angle of your jaw.

- Once you have located the carotid pulse, slide your fingers slightly to the side, towards the midline of your neck. You should be able to feel a slightly thicker, cord-like structure, the carotid sinus.

- Gently massage the carotid sinus area by lightly stroking your fingers up and down the cord-like structure for 5–10 seconds. Avoid pressing too hard.

- During the massage, monitor your consciousness. Stop the massage immediately if you experience any dizziness, nausea, or other concerning symptoms.

4 Safety Warnings:

- Don’t do a carotid massage if you have a history of vascular conditions.

- Don’t hard-massage the carotid sinus, as it can cause lightheadedness and fainting.

- Don’t massage both carotids at the same time. Keep a 10- to 20-second gap between each side.

- Don’t press the carotid sinus for too long, as it can block the nearby carotid artery to turn off the blood supply to your brain.

3. Looking At A Peaceful Scene.

Now, look at this picture — Supermoon of November 13, 2016, shot by Linda Schafer, California.

While looking at the soft, large moon rising from the horizon, the trees in silhouette, and the distant line of mountains against a scarlet sky, you might have unconsciously taken a slow, deep breath.

If you haven’t, and if you are not feeling too self-conscious, take a slow, deep breath. Try it now: one slow, deep breath while gazing at the picture for a few unbroken seconds.

Once you’ve done that, notice how it relaxes you almost instantly. Because inhaling deeply has always done so; we’re born with this ability.

It is a body process that stimulates the vagus nerve via the partition between our chest and abdomen, called the diaphragm.

So, the credit for that deep-breathing-induced relaxation goes to our body’s “wandering nerve,” or the vagus nerve.

[FYI: A Supermoon occurs when Earth, moon, and sun all line up with the moon at its nearest to Earth. It can be around 14% bigger and 30% brighter than a full moon at its farthest from Earth. Astronomers call it the Perigee Moon.]

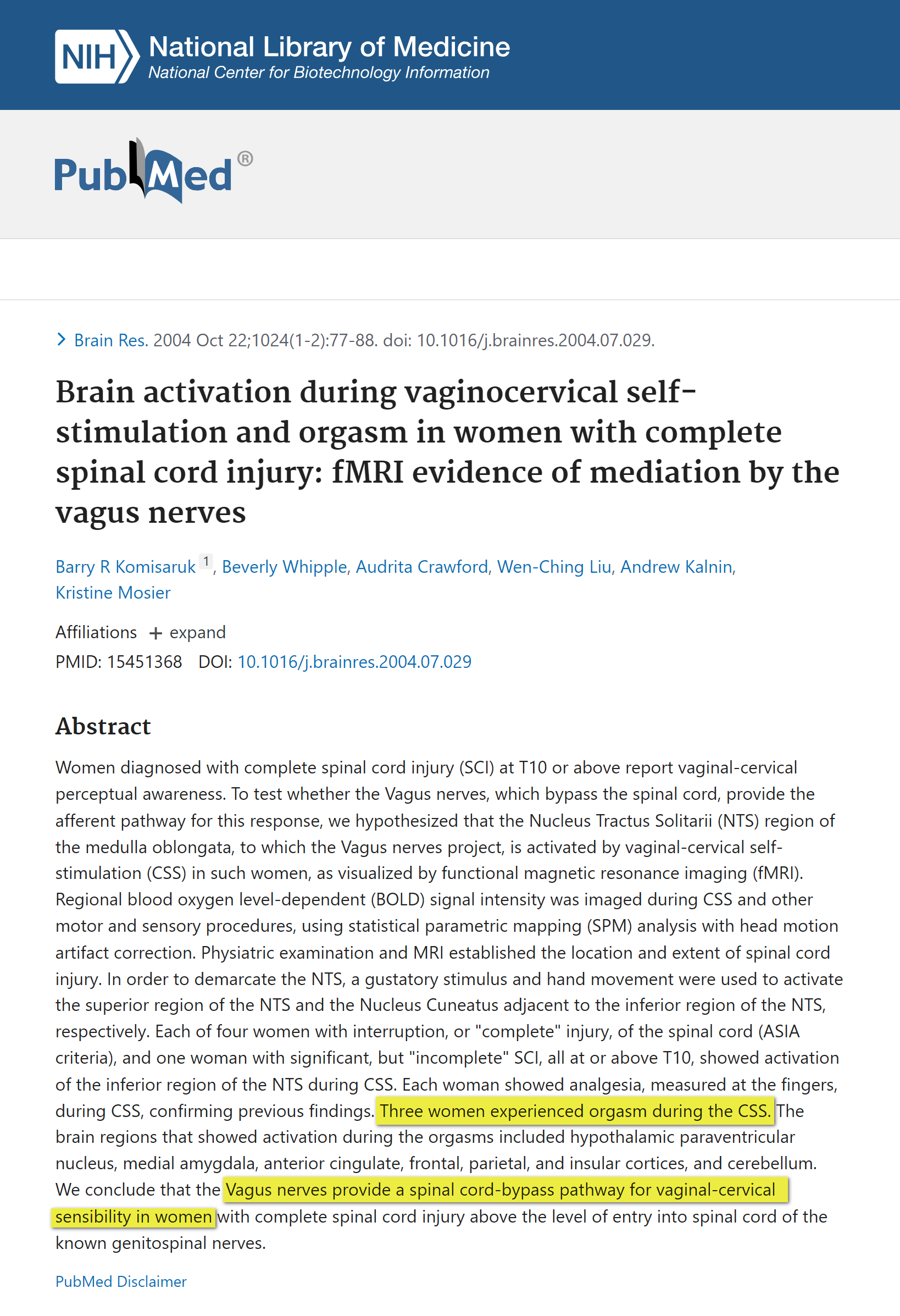

4. Vagus Nerve And Sensory Response in Women.

The vagus nerve plays a key role in women’s sensory response.

This study used fMRI to examine brain activity in four women with complete spinal cord injuries during pelvic sensory activation. The findings were:

- All four women showed activation in the Nucleus Tractus Solitarius (NTS) area of the brainstem.

- Three of the four women reported heightened sensory responses during pelvic sensory activation

- (referred to as CSS in the paper).

- The brain areas that lit up included areas tied to emotions and sensory processing, such as the hypothalamus, amygdala, and parts of the cortex.

Researchers concluded the vagus nerve enables women with complete spinal cord injuries to experience pelvic sensory responses. This is possible because the vagus nerve provides a spinal cord-bypass pathway for sensory connections from the pelvic region to the brain, independent of the known pelvic neural pathways.

5. Practicing Gratitude.

This study found that practicing gratitude can lower heart rate, reduce stress, and make one feel more relaxed in mind and body.

The effects of gratitude were likely due to the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. This was shown by the participants’ steady decrease in heart rate, mediated by the vagus nerve.

- Find a Quiet Space: Choose a comfortable and quiet place where you can relax without distractions.

- Start with Deep Breathing: Spend the first minute focusing on your breath. Take slow, deep breaths in and out. This will help calm your mind and body.

- Focus on Appreciation: After you’ve relaxed, think about someone you appreciate, like your mother. Visualize her and focus on the feelings of love and gratitude you have for her. Think about specific things she has done that you are thankful for.

- Use Guided Messages: If possible, listen to audio or watch a video that guides you through this process. You can find gratitude meditation videos online that help you concentrate on feelings of appreciation.

- Maintain Your Focus: Spend about 4 minutes keeping your thoughts centered on gratitude. Allow yourself to fully experience the positive emotions that come with this focus.

- Reflect on Your Feelings: After the practice, take a moment to notice how you feel. Acknowledge any changes in your mood or physical sensations, such as feeling more relaxed or happy.

- Make it a Habit: Try to practice this gratitude exercise regularly, whether it’s daily or a few times a week, to enhance your overall well-being.

• 8 More Ways To Relax Your Vagus Nerves

- Hearty, mirthful laughter — A few moments of deep, belly laughter can engage the diaphragm and stimulate the vagus nerve, and almost instantly lift your mood. Studies show when people feel more positive emotions, their vagal tone increases, and they have better physical health and better social connections.

- Splashing cold water on the face — Cold exposure is a known way to activate the vagus nerve. You could splash cold water on your face, wash your feet with cold water, take a cold shower, dip in an ice-bathtub, or dip your face in a bowl of ice-water.

- Coughing and gargling — Gargling with water or making humming sounds can stimulate the vagus nerve via the throat muscles. Coughing or throat reflexes can also have the same effect.

- Valsalva maneuver (breathing out with nose held closed) — Take a deep breath. Hold it by closing your windpipe at the throat (using the glottis), as if you are about to cough. Then, still holding your breath, push down your belly, as if straining the abdomen. This raises pressure in your chest, which can trigger your vagus nerve.

- Tightening abdominal muscles — This maneuver, similar to the Valsalva technique, can stimulate the vagus nerve.

- Holding your breath until almost breathless — Temporary breath-holding can trigger the diving reflex. This reflex evolved to conserve oxygen when the body is immersed in cold water, like when diving or swimming. It is mediated via the vagus nerve. It slows down the heart rate, redirects blood flow away from the hands and feet to the heart and brain, and makes the spleen release stored red blood cells.

- Slow exercises like yoga — Yoga can activate the vagus nerve by combining gentle movement with deep breathing.

- Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) — Loving-kindness meditation, or “metta” meditation, involves sending unconditional love and goodwill to yourself and others, whether they “deserve” it or not. Scientists have found that loving-kindness meditation can increase vagal tone and produce greater cardiovascular health.

How Exactly The Vagus Nerve Calms You

A stimulated vagus nerve releases the antianxiety neurotransmitter called Acetylcholine (ACh). ACh relaxes the smooth muscles in our artery walls, dilates the arteries, and slows down our heartbeats.

Christopher Bergland, an ultramarathoner and endurance athlete, writes in his book The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss:

“The vagus nerve is the commander-in-chief when it comes to having grace under pressure.”

What Is Vagal Tone

Your vagal tone reflects how active and healthy your vagus nerves are. It is clinically measured by your heart rate variability (HRV), or the beat-to-beat variations.

A high vagal tone (i.e., high HRV) indicates the vagus nerves are healthy and doing their duties well.

- Better vagal tone = better overall health.

- Those with high vagal tone can deal better with stress.

- A strong vagal tone is found in people who regularly go to the gym, jog, practice yoga, or play a sport.

A low vagal tone (i.e., low HRV) can be unhealthy for us, as it has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease and severe health complications.

- A low vagal tone can cause symptoms like constant fatigue, allergic reactions, migraine, tinnitus, and mood disorders.

- Those with unhealthy lifestyles, such as excessive drinking, smoking, sedentary lifestyles, and being overweight, have low vagal tone.

- A low vagal tone is also seen in digestive disorders and inflammatory bowel diseases.

Facts About The Vagus Nerve

“Vagus” comes from Latin, meaning “wandering,” and so the nerve is also called the “wandering nerve.”

The vagus nerves are important for these things:

- Controlling the parasympathetic or the “rest and digest” nervous system of our body

- Regulating involuntary bodily processes like heartbeat, breathing, and digestion

- Regulating the smooth muscle contraction during bladder function

- Regulating the release of tears, saliva, and stomach acid

- Inducing nausea or fainting if excessively stimulated

- Controlling the body’s inflammatory reflex

- Triggering cough and gag reflexes

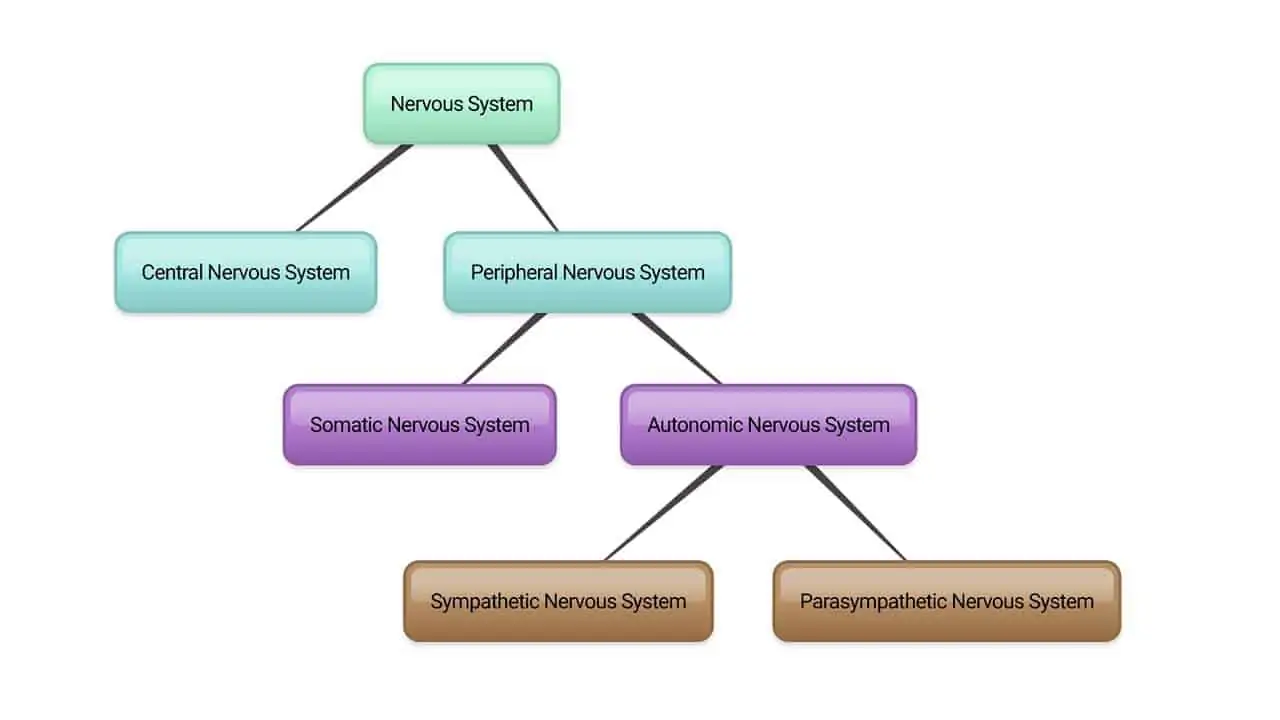

Since we are on the parasympathetic system, let’s get a view from above of our nervous system:

- Our nervous system has two parts: central and peripheral.

- Central nervous system consists of the brain and spinal cord.

- Peripheral is made up of nerves that branch out from the brain and spinal cord.

- The peripheral system is divided into the somatic and the autonomic nervous systems.

- The autonomic nervous system is then divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

The Sympathetic nervous system controls our body’s functions when we are on high alert. It acts to put up a fight-or-flight or stress response.

The Parasympathetic system controls sensory arousal, produces saliva and tears, and regulates bladder function, digestion, and defecation. The vagus nerve is a main part of the parasympathetic nervous system.

- It brings sensory information from the inner organs—the heart, lungs, gut, and liver—to the brain.

- Its motor functions involve moving the muscles that help in speaking, swallowing, and moving the bowels for digesting food.

“The vagus connects the brain to the gut.”

What is Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)?

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) is a medical method to stimulate the vagus. A small device placed under the chest skin sends mild electric impulses to the brain via the vagus.

- Approved by the FDA for the treatment of two chronic conditions: epilepsy and autism.

- VNS also appears to be a promising option for treatment-resistant depression and anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Patrick Ganzer’s study found VNS therapy with rehabilitation helped recover 75% more forelimb strength than rehabilitation alone after a cervical spinal cord injury.

- VNS has also benefited people who suffer from chronic pain and stiffness.

- Neurosurgeon Kevin J. Tracey discovered that stimulating the vagus nerve with electricity can reduce inflammation of rheumatic arthritis.

Loewi’s Dream of Frogs – And Vagus

This is the true story of how a scientist dreamed of frogs, conducted an experiment, and won the Nobel Prize — all thanks to the vagus nerve.

In 1921, German scientist Otto Loewi had a dream in which he solved how information crossed synapses, the tiny gaps between nerve cells. He scribbled notes and went back to sleep, but couldn’t read them the next morning.

Luckily, he had the same dream the next night, and this time he rushed to the lab right away to test it.

He placed two beating frog hearts in two saline jars, the first one with the vagus nerve attached. When he stimulated this heart electrically, it slowed down. Then he poured its saline into the second jar, and found the second heart slowed down too.

Loewi reasoned that a chemical, which he named “Vagusstoff,” released into the saline by the first heart caused the second heart to slow. He later discovered it came from the vagus nerve, not the heart.

Henry Dale, with whom Loewi collaborated in 1902 at University College London, renamed this chemical as Acetylcholine (ACh).

In 1936, Loewi and Dale won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the first neurotransmitter: ACh.

FAQs

Does the vagus nerve cause sweating?

Vasovagal syncope (pronounced SING-kuh-pee) is a sudden fainting spell, with low blood pressure and pallor. Common causes are overstimulating the vagus nerve, sudden change in posture, severe pain, emotional stress, and extreme fatigue.

What are the functions of the vagus nerve?

Some of its other functions are:

1. Memories: Recent research hints vagus nerve stimulation could help strengthen our memories, offering potential cognitive benefits.

2. Inflammation: The role of the vagus in keeping down the inflammation in our body is also a promising direction of research.

3. Resilience: Those with a stronger vagal response, who get more affected by vagus nerve stimulation, might recover better after a stressful event (resilience).

4. Substance Abuse: This study found vagus nerve stimulation can support healthier behaviors and reduce reliance on harmful habits.

Does cold-water face immersion activate the vagus nerve?

Can a cold shower reduce depression?

✶ Cold showers performed once or twice daily (20 degrees C, 2-3 min, preceded by a 5-min gradual adaptation) can have an anti-depressive effect (Shevchuk, 2007).

✶ 32 male volunteers habituated to cold water had a lower stress response when later asked to work out in a low-oxygen environment (Lunt & Barwood, 2010).

✶ 61 people who swam in cold seawater for ten weeks had better moods than 22 of their friends/family who watched them from shore (Massey & Kandala, 2020).

Can cold water immersion be dangerous?

The cold shock response peaks at 50-59°F (10-15°C). Water colder than this offers no extra benefits.

Precautions: Consult your doctor before trying cold plunges. Avoid head-first dives. Have an exit strategy before entering the cold water.

Final Words

Finally, calming the vagus nerve can help us regulate food intake and support weight management. In the paper titled Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders, the authors write:

“The vagus nerve is an essential part of the brain-gut axis and plays an important role in the modulation of inflammation, the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, and the regulation of food intake, satiety, and energy homeostasis. Moreover, the vagus nerve plays an important role in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders, obesity as well as other stress-induced and inflammatory diseases.”

√ Also Read: Why Should You Be More Grateful In Life?

√ Please spread the word if you found this helpful.