Today's Monday • 5 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

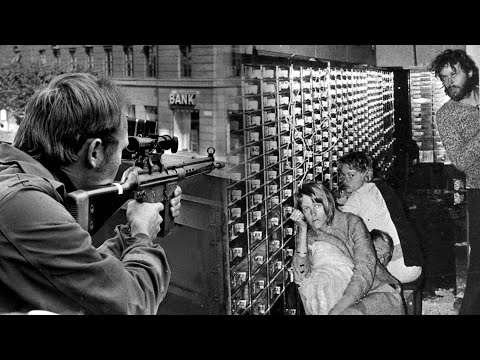

In 1973, four hostages emerged from a bank vault in Stockholm after six days of captivity. They refused to testify against their captors. One woman later got engaged to one of the robbers.

Psychiatrist Nils Bejerot coined “Stockholm Syndrome” to explain this baffling loyalty.

Fifty years later, the term saturates pop psychology and podcasts. Many use it interchangeably with “trauma bonding” to explain why abuse victims stay with their abusers.

Both Stockholm syndrome and trauma bonding have the victims grow emotional bonds with their abusers. But they differ in many crucial ways that affect how we understand and treat them.

Stockholm Syndrome vs. Trauma Bonding: The Core Distinction

Stockholm Syndrome describes a specific response to acute captivity. Someone held hostage develops positive feelings toward their captor as a survival strategy.

- The timeline is compressed: days or weeks, not months or years.

- The victim has zero choice about the relationship’s existence.

Trauma bonding unfolds differently. It develops gradually within ongoing relationships where the victim initially chose to participate.

- The abuser alternates between cruelty and kindness, creating an addictive cycle.

- The victim becomes emotionally dependent through intermittent reinforcement, not just fear.

How Common Are Each

An FBI study of over 1,200 hostage incidents found that 8% of kidnapping victims showed signs of Stockholm Syndrome (Fuselier, 1999).

That drops to 5% when you exclude those who simply expressed anger at law enforcement rather than a genuine attachment to captors. Those numbers reveal how rare the phenomenon actually is.

Trauma bonding prevalence remains harder to measure because it occurs in private relationships without clear endpoints.

Researchers estimate it affects a substantial portion of domestic abuse survivors, but no consensus exists on exact figures.

Why the Confusion Persists

Both involve emotional attachment to someone causing harm. Both make outsiders ask the same frustrated question: “Why don’t they just leave?”

The mechanics differ.

Stockholm Syndrome operates through immediacy and helplessness.

A hostage has no prior relationship with their captor and no illusion of control. The positive feelings emerge as a psychological shield against overwhelming fear.

Trauma bonding builds on a foundation of intermittent reinforcement. The abuser offers genuine moments of affection between episodes of cruelty.

These unpredictable rewards trigger the same neurological patterns as gambling addiction. The victim keeps hoping the “good” version will become permanent.

Kristin Enmark was one of the hostages during the 1973 Stockholm bank robbery. She later challenged the concept itself.

In her 2015 book, “I Became the Stockholm Syndrome,” she wrote she was simply trying to survive by cooperating with her captors. It was how she protected herself from what she claimed was dangerous police incompetence.

Her statement highlights a key problem: we often pathologize rational survival strategies as psychological disorders.

What Research Actually Shows

Stockholm Syndrome never made it into the DSM. Research on it remains sparse and contradictory.

What little exists focuses almost entirely on hostage situations and kidnapping, leaving questions about whether the same mechanisms apply to domestic abuse.

The 1973 Stockholm incident involved specific conditions:

- prolonged isolation,

- complete dependence on captors for basic needs,

- small acts of kindness against a backdrop of fear, and

- no immediate means of escape.

Replicating these exact conditions in other contexts proves difficult.

Trauma bonding research faces different obstacles. The phenomenon occurs behind closed doors.

Victims often don’t recognize it while it’s happening. By the time they seek help, memories may be distorted by ongoing psychological manipulation.

Psychiatrist Patrick Carnes developed the most comprehensive framework for understanding trauma bonding in his 1997 work on betrayal bonds (Carnes, 1997).

Carnes identified seven stages: love overloading, trust and dependency, criticism, gaslighting, resignation, loss of self, and addiction.

Each stage reinforces the next, creating a trap that tightens incrementally.

The Patty Hearst Case

Patty Hearst’s 1974 kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army blurred the lines entirely.

After two months in captivity, she participated in bank robberies with her captors. She took the name “Tania” and recorded messages denouncing her family.

Her case became the most cited example of Stockholm Syndrome.

Yet it also contained elements of trauma bonding: extended duration, ideological indoctrination, physical and intimate abuse, and intermittent reinforcement of behavior through approval and punishment.

The jury convicted her of bank robbery. President Carter later commuted her sentence, and President Clinton pardoned her.

The legal system struggled with the same question psychologists still debate: where does survival instinct end and genuine attachment begin?

Recognition and Recovery

Both patterns share warning signs:

- The victim defends their abuser’s actions.

- They minimize or justify abusive behavior.

- They feel anxious about displeasing the abuser.

- They experience isolation from friends and family.

- They develop an intense emotional dependence that feels impossible to break.

Treatment approaches overlap but require different emphases.

Stockholm Syndrome victims often need acute trauma processing focused on a specific incident. The intervention happens after release from captivity.

Trauma bonding requires unpacking years of conditioning. Victims must recognize patterns they didn’t see while living through them. Recovery involves rebuilding a sense of self that eroded gradually over time.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy helps both groups challenge distorted thinking patterns. Trauma-focused approaches address underlying PTSD symptoms. Building social support networks counters the isolation that both phenomena create.

Final Words

“Don’t paint a picture of a toxic relationship and sell it as romance.”

The key insight: neither represents weakness or dysfunction. Both are survival adaptations to impossible situations. The brain protects itself by finding ways to coexist with inescapable threats.

Knowing the distinction matters for treatment, legal proceedings, and public perception. Conflating the two obscures the specific mechanisms that trap victims and the targeted interventions that free them.

If you recognize these patterns in yourself or someone you care about, seeking professional help from a trauma-informed therapist represents the first step toward breaking free.

Recovery takes time, but attachment formed under duress can be unwound with proper support.

√ Also Read: How To Break Trauma Bond With A Narcissist In Your Life?

√ Please share this with someone.

» You deserve happiness! Choosing therapy could be your best decision.

...

• Disclosure: Buying via our links earns us a small commission.