Today's Sunday • 10 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

The fundamental attribution error (FAE) is when we think someone made a mistake because they’re a bad person, and it’s in their nature, not because of circumstances.

“Why do we quickly pin other people’s mistakes on their character, yet give ourselves a pass for making the same mistake?”

- When an office colleague is late to a meeting, we are quick to conclude they are habitual latecomers even before they get a chance to explain their position.

- When we are late for a meeting, we expect people to understand there must be a valid reason behind it, such as an emergency involving a close friend.

See the difference? We have different yardsticks to measure our flaws against theirs.

Did you know that this research found a consistent link between vulnerable narcissism and hostile attribution bias?

Summary

- Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE) makes us judge ourselves and others by different yardsticks.

- It allows us to treat ourselves with leniency but hold others fully accountable for their actions.

- It can make us form lasting impressions of a person’s character based on limited information.

- It can lead to heated arguments, unnecessary disruptions, and malicious acts.

So, if you know someone who constantly blames you for things beyond your control, they might be a vulnerable narcissist.

1. What is the fundamental attribution error?

The Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE) is the irrational tendency to pin a person’s mistake on their very character, without considering that events beyond their control might have caused it. It is a common cognitive bias that involves making snap judgments about other people’s faults.

FAE is also known as attribution bias, correspondence bias, or over-attribution effect.

This person, who blames others for their faults, usually doesn’t approve of that behavior — whether in themselves or in another person. But they justify themselves, while not allowing others to justify their actions.

A common example of FAE is branding an employee lazy, unreliable, dishonest, and even “disgraceful to the company culture” when they are late a few times due to unavoidable situations.

We are great advisors, but poor doers.

We often realize situations might have shaped someone’s decisions. But we are quick to pass judgment on their nature:

- “You are always careless.”

- “You are always making up excuses.”

- “You are always finding new ways to show up late.”

As they say, there is a mile-long gap between knowing it and doing it.

The surprising part is that we know judging others based on limited information is wrong. We even caution our friends against it.

But surprisingly, we still hold them guilty by nature.

Quirks of FAE

Some other quirks of FAE:

- FAE can lead to seeing the person who made a mistake in a bad light for a long time, even if they never make the same mistake again.

- FAE can make us overappreciate our own capabilities. It makes us attribute our good performance to our better skills and effort, ignoring other people’s contributions.

- FAE can make us believe that our performance is still as good as before, even when we are working under pressure. Since it can be difficult to self-assess our skills at such times, we think we cannot do worse than we did previously.

- FAE can make us justify our veritable mistakes and poor results on external factors when someone else points out our poor performance.

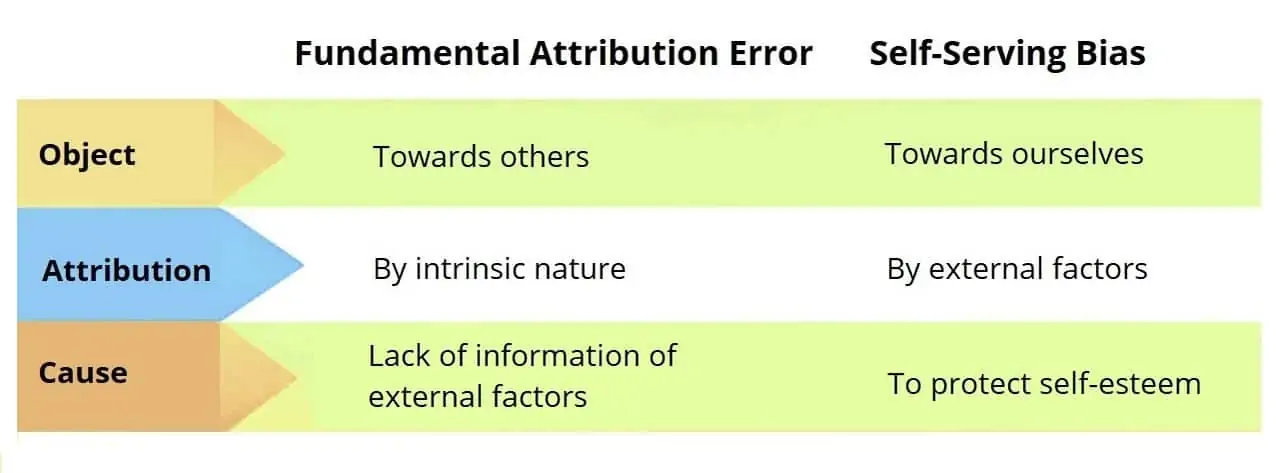

FAE & Self-Serving Bias

The self-serving bias is when people usually attribute desirable outcomes to their personality traits and undesirable outcomes to environmental factors. It’s like:

- “It’s good because I am good at it!”

- “It turned out bad because of that thing/person, not me.”

It makes a person take credit for positive outcomes while blaming others for negative ones.

2. Why do we make fundamental attribution errors?

We make fundamental attribution errors because we are not good at attributing personal actions to external causes. Our brains have evolved to think in terms of self-meaning, which means attributing actions and thoughts to our own actions and thoughts.

Also, we tend to avoid draining our mental energy to analyze a situation. Our mental resources, like willpower, come in limited supply, and so our brains take the quickest route between a problem and a solution while trying to spend the least amount of energy.

This leads us to take mental shortcuts or heuristics, which makes us vulnerable to other cognitive biases. (Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can help us with faster problem-solving and decision-making.)

When asked why we judge others for their situational behavior, we shield ourselves with the credible excuse of unawareness. We say we blamed them because we did not have all the facts in our hands, like “I wasn’t aware of her situation!”

But research takes the lid off this charade. People commit FAE even when they have a fair idea about the whole situation.

When our mind processes another person’s actions, it has to step across three hurdles:

- First, we compartmentalize the conduct (that is, what’s this person doing?).

- Second, we make a dispositional characterization (that is, what does this conduct hint about his personality?).

- Third, we apply a situational correction (that is, what aspects of the situation might have contributed to this conduct?).

While the first two actions happen automatically, the third step requires a deliberate effort on our part.

So we often skip this step, especially in situations where we don’t have the cognitive wherewithal to go through it.

3. How do we make fundamental attribution errors?

A fundamental attribution error occurs when people pay too much attention to the action itself or attribute the action to their internal dispositions. Whereas they fail to consider the possibility it could have been caused by another person.

People have poor knowledge of the other parties’ intentions or goals. It’s also likely that we don’t know the full story of their behavior. We quickly rely on our own personal experience or our gut feelings to guide what we say and how we act, rather than seeing all the variables.

As the famous quote from Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky states:

People project their judgment from others onto themselves.

When we assume a person’s behavior has been intentional, we believe their behaviors come from a place of character and therefore personal responsibility.

In other words, we think others should have to pay for what they did. This makes for revengeful behavior.

4. What are examples of fundamental attribution errors?

There are many ways that people misattribute the causes of events.

Example 1

A person may blame a fire on a faulty wire or bad ventilation. When a fire occurs in a flammable building, the cause usually becomes clear: the broken sprinkler system. And no one knows for sure who is responsible for starting the fire.

That broken sprinkler head did not start the fire, though it let the fire spread.

But people with this bias, including firefighters, are quick to point their fingers at the sprinkler system.

Example 2

In a classic study by Edward Jones and Victor Harris, university pupils read essays that either defended or condemned Fidel Castro, the leader of the Communist Party of Cuba.

Some participants were told the author had themselves chosen whether to write for or against Castro, while others were told the writers received instructions to write from an assigned position.

The results surprised the experimenters.

Even when the participants were told the author had no choice, they still believed the author’s opinions about Castro were compatible with the argument made in the essay.

Other studies have shown that this effect happens independently of participants’ own opinions. Whether they received more information about the author or got instructions to avoid bias, they still made the same mistake of fundamental error.

Example 3

Another example. Let’s say a gang of burglars broke into your house. They steal a safe. The police raid the house, find the safe, and arrest the burglars.

You recorded everything on video. So you report the incident to the police and let them know you called them while it was happening. The police officers ask you for a description of the burglars. You say there were three men wearing scarves covering their faces, but not much else.

Soon after, someone calls the police station and gives them a description of the burglars. They show the police officers the video you took before the raid. Based on this, the police officers now arrest you and charge you with burglary.

Why would the police arrest you for an incident you did not have a part? It sounds absurd, right? It is. The wrong ownership of an act is an example of the over-attribution bias, or the fundamental attribution bias.

5. When are we more likely to make fundamental attribution errors?

We are more likely to blame others for their failures and assign motives to their acts. But when are we more likely to commit FAE, even though we know it is the situation, not the person, that is to blame?

- We make FAE because it saves us mental energy.

- We are more likely to do it when we are mentally exhausted.

- We tend to do it when we are too busy and running short of time.

- Happy mood increased dispositional attributions, while sad mood decreased them.

People readily link the success of others to their circumstances (luck?!) but blame their failures on their personalities. They also give positive tones to their own motives, but negative tones to those of others.

6. How can we avoid making fundamental attribution errors?

FAE is deeply rooted in human psychology, and we cannot overcome it entirely. The best way to avoid it is to see others with empathy, kindness, acceptance, and self-regulation.

Most biases can be handled well if we can force ourselves to analyze the situation more objectively, and give ourselves more time to make our decisions.

Gilbert et al. (1988) conducted a study in which participants saw a (silent) videotape of a woman behaving anxiously.

- For half of them, the videotape’s captions indicated the woman was answering questions on topics that would make her uncomfortable, such as intimate fantasies.

- The other half had captions that displayed it was an interview discussing uninteresting topics, such as world travel.

- The researchers also told some of them (as they watched the tape) that they would have to take a recall test later (to overload their cognitive capacity). This is called Cognitive Busyness.

When the participants were cognitively busy, they were more likely to attribute the woman’s gestures to anxiety and say she was an anxious person in general.

So, we can avoid being swayed by this bias if we are relaxed, and do not have too many worries and concerns weighing down our minds when a person explains their situation.

Further Reading on FAE

- How fundamental is the fundamental attribution error?

- A fundamental attribution error? Rethinking cognitive distortions.

- The Really Fundamental Attribution Error in Social Psychological Research.

- On being happy and mistaken: Mood effects on the fundamental attribution error.

- From the fundamental attribution error to the truly fundamental attribution error and beyond: My research journey

Final Words

Now that we have a fair idea about why we underestimate the influence of the situation on people’s behavior, we could train ourselves to listen to their stories patiently.

But, as Sacks (2011) points out, many psychological experiments that have not been carefully controlled are of little use, “because they can produce a high degree of both bias and error.”

√ Also Read: 13 Cognitive Biases (Or Why You Make Bad Decisions)

√ Please share this with someone.

» You deserve happiness! Choosing therapy could be your best decision.

...

• Disclosure: Buying via our links earns us a small commission.