Reading time: 18 minutes

— Researched and written by Dr. Sandip Roy.- Empathy is our ability to imagine what the other person might be thinking or feeling.

- Empathy is our ability to feel the emotions of another person as our own.

- David Brooks calls it a “social emotion.”

- And it is also an attitude.

Empathy has three sides — the ability to recognize and feel another’s emotions, understand their thoughts and views, and use those insights to respond helpfully.

Table of Contents

Empathy Definition

Empathy is the ability to imagine and understand what someone else might be thinking or feeling. It is also an ability to experience another person’s emotion (painful or pleasant) as they feel it.

- Bruce D. Perry: “The essence of empathy is the ability to stand in another’s shoes, to feel what it’s like there. Your primary feelings are more related to the other person’s situation than your own.”

- Carl Rogers: “Empathy is the listener’s effort to hear the other person deeply, accurately, and non-judgmentally.”

- Carl Rogers: “To have empathy is to sense the hurt or the pleasure of another as he senses it.”

- Maya Angelou: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

The Evolution of Empathy

- 19th Century: Empathy originated from the Greek “empatheia” meaning a sense of deep passion.

- 1873: Robert Vischer, a German philosopher, was the first to use the word “Einfühlung” to explain the emotional “feeling in” with a work of art. Later, another German philosopher, Theodor Lipps, in his Aesthetik, expanded it to mean “feeling one’s way into the experience of another.”

- 1909: The English psychologist Edward Titchener coined the word “empathy” as we know it today, in 1909, as a translated version of the German word einfühlung.

Biologically, empathy is a survival tool. The roots of empathy lie in our genes that we inherited from our ancestors.

Empathy helped human ancestors to understand and share each other’s feelings, help each other through difficult times, and work together to make a social group thrive.

Empathy probably evolved in the context of the parental care that characterizes all mammals. Signaling their state through smiling and crying, human infants urge their caregiver to take action… females who responded to their offspring’s needs out-reproduced those who were cold and distant. This may explain gender differences in human empathy.

— Frans De Waal, GGSC

Empathy has been found in animals like primates and rats.

What Empathy is Not

- Empathy is not about being weak, it’s about being strong.

- Empathy is not a response that begins with “at least I had it.”

- Empathy is not about being perfect, it’s about being human.

- Empathy is not about being perfect, it’s about being present.

- Empathy is not about being a rescuer, it’s about being a witness.

- Empathy is not about being a doormat, it’s about setting boundaries.

- Empathy is not about fixing someone else, it’s about being with them.

- Empathy is not about fixing the world, it’s about making it a little more bearable.

- Empathy is not about taking on someone else’s pain, it’s about holding space for it.

- Empathy is not about making someone else feel better, it’s about connecting with them.

The True Meaning of Empathy

Scientifically, much of our modern understanding of empathy is based on the works of Carl Rogers, the American psychologist.

In 1975, Carl Rogers wrote Empathic — An Unappreciated Way of Being to propose that human empathy is a process, not a state. That is, empathy does not come in a fixed amount, and all of us can change it for the better or worse.

So, Rogers first told us we can learn to have more empathy.

Imagine a bridge where people walk up and share their opinions, beliefs, fears, and anxieties.

Empathy builds that emotional bridge where people come to share experiences, needs, and desires. Then it motivates us to respond to each other’s suffering with kindness and compassion.

Strange fact: Some people have this strange condition called pathological altruism. They go out of their way to improve another person’s life, even at a risk or cost to themselves. It is common in codependent situations—when one person sacrifices all their comforts to help their partner.

Social mimicry: Some animals show emotional contagion or social mimicry to another animal in pain. But it is not true empathy. True empathy involves self-awareness, while mimicry does not. Human babies can also show this social mimicry; they can smile at you without understanding why you’re smiling.

Finally, having empathy does not mean you agree with the person. You can empathize without having to give them your approval or consensus.

So, it’s empathetic to say, “I can understand you, but I don’t agree with you.”

The 3 Types of Empathy

Paul Ekman, an American psychologist and a pioneer in the field of emotions and micro-expressions, classifies empathy into three types:

1. Cognitive empathy or perspective-taking

The recognizing and understanding of another’s thoughts and feelings. Cognitive empathy is feeling by thinking.

It is the form of empathy that psychopaths have lots of—they understand what causes you the most pain and torture you with exactly that—with zero sympathy towards you.

So, a psychopath can feel empathy, but not sympathy (we have a video by Brené Brown explaining the difference later in this post).

People who score higher on cognitive empathy have more grey matter in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex area of the brain.

2. Emotional empathy or affective empathy

The vicarious sharing of feelings after an emotional interaction. In this, you understand as well as feel how the shoe pinches the other person.

The people in the medical care profession usually have this type of empathy; they fully understand and feel your pain.

This type of empathic response is called empathic distress or personal distress. People who score higher on affective empathy have more grey matter in an area of the brain called the anterior insula.

3. Compassionate empathy or empathic concern

The action part of the previous two types, or an impulse to act after understanding and feeling another’s experience. In this, after you can understand and feel the other person’s woe, you take action to resolve it for them.

Compassion is a tender response to another’s suffering. Compassion comes with a wish to act. In contrast to empathy, compassion does not mean sharing the suffering of the other.

Cognitive empathy is a well-known forerunner of compassionate empathy. Compassion cannot exist without empathy.

Some of you might be interested in this: According to some experts, empathy is different from the Theory of Mind (ToM). The ToM is our intellectual ability to assume and presume other peoples’ beliefs, intentions, and thoughts.

Empathy, on the other hand, is the capacity to understand and share the emotional experiences of others (Gallese, 2003). While the ToM can be seen as “cognitive” perspective-taking, empathy is known as “emotional” perspective-taking.

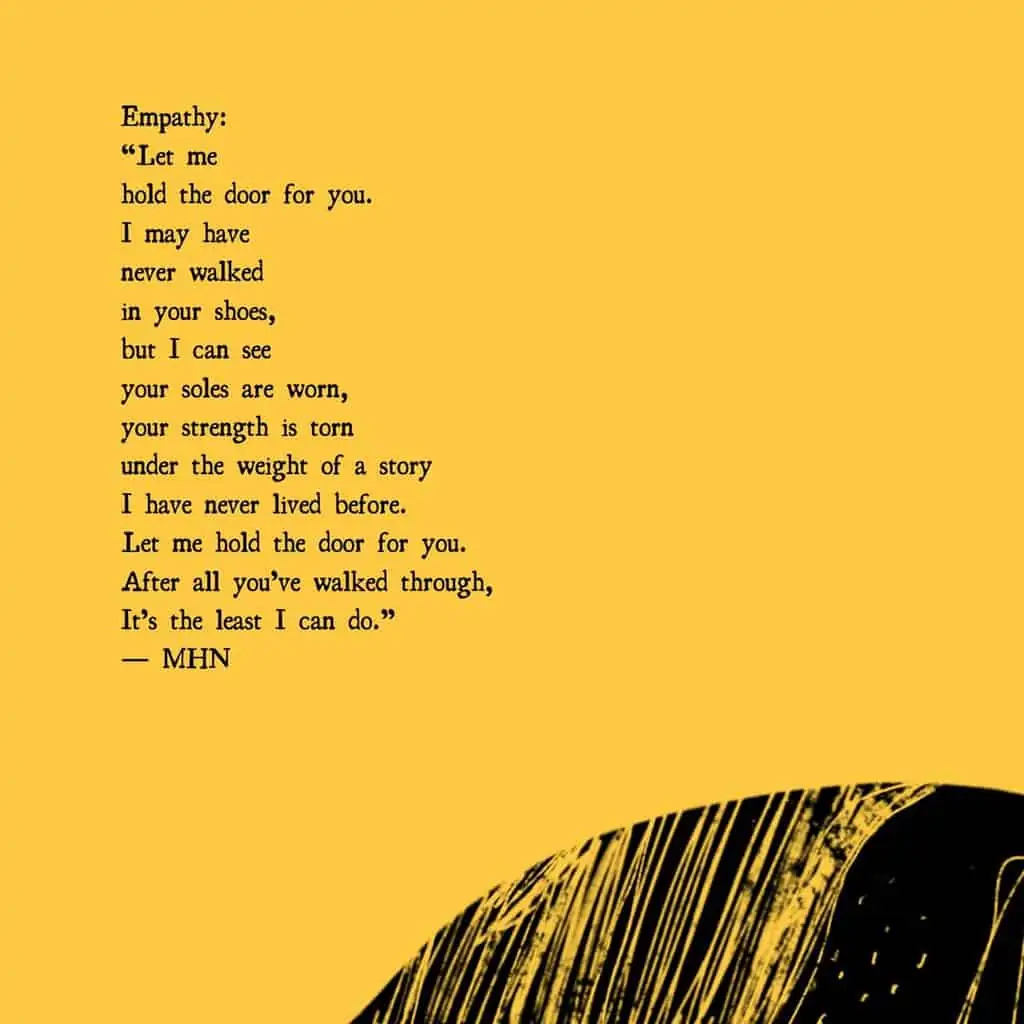

Meanwhile, the poets explain empathy in relationships as only they can:

Where Does Empathy Live In Our Brains?

Studies show that “I feel your pain” is much more than a figure of speech. We actually do feel the pain of others.

Empathy is a hardwired capacity in our brains. Brain research shows there is a “neural relay mechanism” that allows empathic people to subconsciously mimic the postures, mannerisms, and facial expressions of others, as compared to those with less empathy.

Neuroscientists have seen this mirroring capacity even at the level of single muscle fibers. So, if a needle pokes a person’s hand muscle, the same brain areas are activated in the person who is watching it from a distance. Even simply watching or copying an emotional expression stimulates a similar network in the brain of the observer.

We feel another person’s pain, but only in a lessened form. This lessening of the sensation makes it possible for us to empathize but also not get crushed by another’s distress.

From brain scan studies, scientists have zeroed in on a region called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) which becomes active when one experiences pain, and could also become active when one watches others in pain.

Interestingly, the same studies also showed when observing another person’s pain, this region is more active in people with high levels of empathy (and less active in psychopaths).

The Danish research team led by Giacomo Rizzolatti discovered a group of nerve cells in the ACC that become active when a rat sees another rat in pain. These are called “mirror neurons”. Rizzolatti says these cells form the biological basis of empathy and compassion.

Empathy In Building Societies

Empathy is … a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others.

Look at the picture below.

It’s easy to guess these two ladies are listening and talking to each other with empathy. Empathic communication means listening to a person while reflecting, clarifying, and amplifying their experience, without forcing one’s own words into the conversation.

Empathy is understanding another person’s feelings without passing judgment on them. It is a “social emotion” without which we might even become a threat to society. We must have empathy to have good, authentic relationships.

To be empathic is about listening to understand the reality and meaning behind the spoken words. It is listening without judging, trying to change the other person, or thinking up what should our answers be. It is listening with unconditional respect.

Can a relationship last without empathy? Can a society thrive without empathy? No. Empathy was the key tool that got us this far in the Natural Selection game. Without empathy, we wouldn’t have helped each other survive through crises.

Empathy In Early Human Societies

Time for a great story: A student once asked the famous anthropologist Margaret Mead, “What is the earliest sign of civilization?”

The student expected her to say the wheel, a grinding stone, or a weapon. But Mead replied, “A healed femur.”

Mead said the first evidence of civilization was a 15,000 years old healed femur (thighbone) found in an archaeological site. She explained, in the animal kingdom, if you break your leg, you die. You cannot run from danger, get to the river for a drink, or hunt for food. You are meat for the prowling predators. You get eaten. No animal survives a broken leg long enough for the bone to heal.

A broken femur that has healed is the evidence that someone has taken time to stay with the one who fell, has bound up the wound, has carried the person to safety, and has tended the person through recovery. A healed femur indicates that someone has helped a fellow human, rather than abandoning them to save their own life.

Helping someone else through difficulty is where civilization started. And that help could come only after empathy.

Humans Who Lack Empathy

Yes, it is possible for individuals to lack empathy. Its presence may vary along a spectrum, and some people may exhibit a diminished capacity for empathy, while some may even experience a complete absence of it.

Genetic factors, upbringing, social factors, and life experiences can play a role in hindering the development of empathy.

For instance, those who have experienced trauma or have had limited exposure to empathetic behavior during their childhood may struggle to cultivate empathy later in life.

Certain personality and developmental disorders such as narcissistic personality disorder, sociopathy or antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, alexithymia, and autism spectrum disorder are often associated with a lack of empathetic capabilities.

However, empathy levels can still vary among individuals even if they have the same disorder.

We must realize that lacking empathy does not necessarily mean the individual will remain that way indefinitely.

Empathy is a learnable skill. Individuals with lower empathy may improve it through self-awareness, and education.

How To Have More Empathy In Relationships

Having empathy is a key relationship skill. And like any other skill, we can get better at it through practice. Rick Hanson, a psychologist, suggests empathy can be practiced better by expressing these four basic skills:

- Paying attention – listening with full attention, without interrupting, to what they are saying, keeping the focus on their experience.

- Inquiring – asking open-ended questions relating to what they are talking about (e.g., How do you feel about him/her? or What do you think they’ll do?).

- Digging down – trying to find more about their story, the deeper emotions behind their expressed feelings, imagining how the person might be suffering from inside, wondering how their experiences have shaped them thus.

- Double-checking – repeating to them what they are saying to keep it clear what they are saying (e.g., “Let me say back what I hear you saying. Are you saying that …?”)

The Dark Side of Empathy

Empathy has a dark side too. By the dictates of evolution, nature wired us to empathize most with those who are alike. We don’t seem to care much for others who are socially and culturally different from us. Emotional empathy, or emotional sharing, most easily occurs among members of the same “tribe.”

We have maximum empathy for those who look like or act like us. We feel the most for those who have suffered like us or with whom we share a common goal. This results in biases in various communities and can take the extreme form of racism. Learn more about the five hurtful ways of empathy.

Empathy vs. Sympathy

In this lovingly animated short video by RSA, Brené Brown reminds us we can create a genuine empathic connection only when we are brave enough to get in touch with our frailties.

“Sympathy is feeling sorry for someone, while empathy is feeling with someone.”

Here are 7 takeaways from the video:

- Empathy is the most radical act of love.

- Empathy is perhaps the best way to ease someone’s pain and suffering.

- Empathy is like a sacred space where someone feels connected and supported.

- Empathy is the ability to take the perspective of another person and recognize their perspective as their truth.

- Empathy involves staying out of judgment, recognizing emotions in others, and communicating that empathy.

- Empathy is a vulnerable choice because it requires connecting with something in oneself that knows that feeling.

- Sometimes the best empathic response is to simply say, “I don’t even know what to say right now, but I’m just so glad you told me.”

FAQs

What are some practical tips for building cognitive empathy?

Here are some ways you can build your cognitive empathy:

1. Practice Active Listening: Engage fully in conversations by giving your undivided attention, maintaining eye contact, and avoiding distractions.

2. Suspend Judgment: Approach conversations with an open mind, setting aside your biases and preconceptions.

3. Ask Clarifying Questions: Seek to understand the other person’s perspective by asking open-ended questions that encourage more discussion.

4. Reflect Back Emotions: Acknowledge and validate the emotions expressed by the other person, showing that you understand their feelings.

5. Observe Nonverbal Cues: Pay attention to unspoken cues like facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice to gain insights into their deeper emotions.

6. Consider Different Perspectives: Try to see the situation from the other person’s point of view, even if you disagree with their perspective.

7. Emphasize with Similarities: Identify shared experiences or emotions you have had that resonate with the other person’s situation.

8. Read Fiction and Watch Emotional Films: Read and watch stories that explore human emotions and relationships to immerse yourself in different perspectives that may never happen in your life.

9. Practice Perspective-Taking Exercises: Practice exercises that ask you to imagine yourself in the shoes of another person.

10. Cultivate Self-Awareness: A strong understanding of your own emotional landscape can help you respond better to the emotions of others.

Why do some people not develop compassionate empathy?

Some individuals may not develop compassionate empathy due to the perceived costs associated with it, including the mental effort, time commitment, and emotional weight it entails.

How does emotional avoidance impact the development of empathy?

Emotional avoidance can hinder empathy development by disallowing the avoidant person’s exposure to various human emotions and expressions.

People may tend to actively avoid sources of distress relating to the difficulties of others when they are in emotional exhaustion or burnout. The reason for their avoidance is to protect themselves from further emotional strain. Their need to safeguard their own well-being limits their ability to empathize with others.

How does prolonged stress affect tolerance and cognitive empathy?

Prolonged stress can reduce one’s cognitive empathy and therefore, the ability to tolerate the behaviors, emotions, and opinions of others. Long-term stress often makes people less patient and more irritable to the actions of those around them. As a result, they often overreact to even minor irritations.

Moreover, the ongoing stress can make it harder for them to provide the necessary support and comfort that empathic people typically offer in social situations.

What is the relationship between emotional intelligence and empathy?

Emotional intelligence (EI) and empathy are closely intertwined, playing a crucial role in interpersonal relationships, personal well-being, and professional success.

High EI individuals tend to be highly empathetic, and empathy is a crucial skill for developing and maintaining strong relationships.

Conversely, absent or low emotional intelligence can lead to a lack of empathy, making it challenging to understand and connect with the emotions of others.

EI covers a range of skills — self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, relationship management, emotional regulation, and empathic responses. So, empathy is one skill in EI.

Also, EI is more about understanding and managing one’s own emotions, as well as the emotions of others, while empathy is more about understanding the emotions of others.

What are the causes of low empathy?

Low empathy, temporary or consistent, can arise from both biological and environmental factors.

One cause of low empathy is genetic predispositions. Research suggests that certain personality and developmental disorders, such as narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), Machiavellianism, sociopathy or antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), alexithymia, and autism, may be influenced by genetic factors and are associated with varying levels of empathy.

Individuals with BPD might have low emotional empathy but show cognitive empathy to some extent. Those with Machiavellianism and NPD, as recent studies suggest, might possess empathy but lack the motivation to express or act upon it.

Autistic individuals often face challenges with cognitive empathy but have emotional empathy. However, expressing empathy might be difficult due to the co-occurrence of alexithymia, rather than being directly related to their autism.

Moreover, since empathy is partially a learned behavior, those who did not experience much empathy during their upbringing, having spent a significant amount of time isolated, and lacked opportunities to practice empathy, may struggle to empathize with others later in life.

What are the signs of low empathy?

Some signs that someone may lack empathy can be:

1. Critical and judgmental behavior: A person lacking empathy tends to excessively criticize others for expressing their emotions or experiencing certain situations. They may even blame the person and refuse to understand their perspective.

2. Inability to understand others’ circumstances: People with low empathy often struggle to connect with or relate to the experiences of others. They may believe that certain events would never happen to them, or presume that they would handle such situations much better.

3. Dismissing others’ emotions as being too sensitive: Due to their difficulty in comprehending others’ perspectives and emotions, individuals lacking empathy may view emotional reactions as invalid or unnecessary. They might act dismissive or fail to acknowledge the significance of someone else’s feelings.

4. Responding inappropriately: Those with low empathy may respond to someone’s emotional expression with jokes or insincere expressions of indifference. They may also have trouble actively listening to others, displaying a lack of genuine understanding and support.

5. Lack of awareness of how their actions affect others: People lacking empathy often fail to recognize or acknowledge the impact of their behaviors on others. Even if they do understand, they may not feel any remorse or take responsibility for the consequences of their actions.

6. Difficulty maintaining meaningful relationships: Low empathy frequently leads to ongoing difficulties and conflicts within relationships. When individuals struggle to understand others’ emotions or fail to act in a supportive manner, it becomes challenging for them to form deep, meaningful connections with others. As a result, they may have few or no genuine interpersonal relationships.

Books On Empathy

- Emotions Revealed — Paul Ekman

- The Empathy Effect — Helen Riess

- Against Empathy — Paul Bloom

- The Art of Empathy — Karla McLaren

- Empathy: A History — Susan Lanzoni

- Intellectual Empathy — Maureen Linker

Final Words

Empathy is in shared happiness as much as in shared suffering.

When people have difficult conversations, they often try to make things better by saying things that turn out to be counterproductive.

Sometimes the best empathy is just being there for them in their hour of challenge, sensing their emotions in silence.

√ Please share it with someone if you found this helpful.

√ Also Read: Stephen Hawking Told Us, Why Is Empathy Important In Society

• Our Story!