Today's Monday • 13 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

It’s hard to imagine that Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the world’s most powerful ruler, found time to be happy during his reign.

Marcus Aurelius came to the throne in 161 CE and went into war just five years later. The major part of his reign was spent in the Marcomannic Wars. To make things worse, the Antonine Plague broke out in 165 CE and ravaged the Roman Empire for fifteen years.

Yet, despite these external threats and inner battles, Marcus still found a way to live with purpose and even happiness, writing Meditations from the harsh grounds of wartime life.

- At the end of Book I, he mentions “the River Gran, among the Quadi,” referring to the Hron River, a Danube tributary in present-day Slovakia.

- Later, at the end of Book II, he mentions Carnuntum, a key Roman army base near the Danube, close to modern Vienna.

History remembers Marcus Aurelius Antoninus as the last of the Five Good Emperors of Rome. Many call him “The Philosopher King.”

Like many modern readers of Stoicism, I see Marcus as a true Stoic whose insights on a fulfilling life still resonate today.

Marcus Aurelius On Happiness And A Happy Life

Marcus was clear on two points about happiness in life:

- The requisites of a good life and a happy life are the same.

- We don’t need money, fame, or possessions to be satisfied.

For Marcus, happiness came from living according to reason and virtue. He believed that a good person, doing their duty with integrity, naturally lives a happy life.

There’s no separation between being good and feeling fulfilled. One follows the other.

Marcus rejected the idea that happiness depends on external things. He felt that money, status, or luxury offered no lasting sense of happiness.

What matters is the strength of our character, the way we act and think, and our practice of patience, courage, and wisdom, especially in hardship. He believed our inner choices shape our peace of mind.

Marcus Aurelius’ Quotes On Happiness

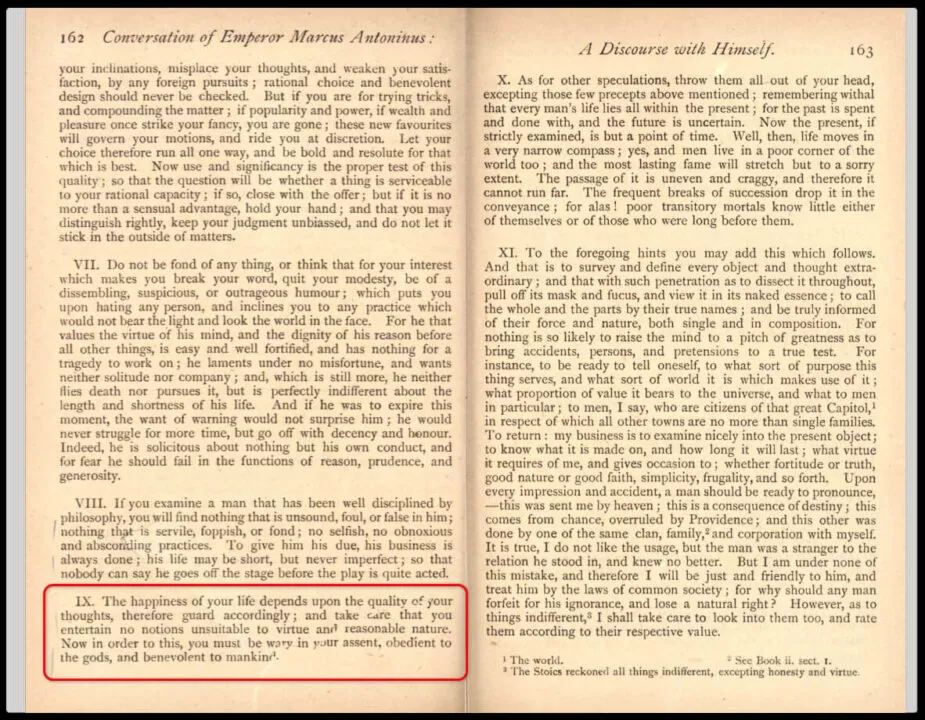

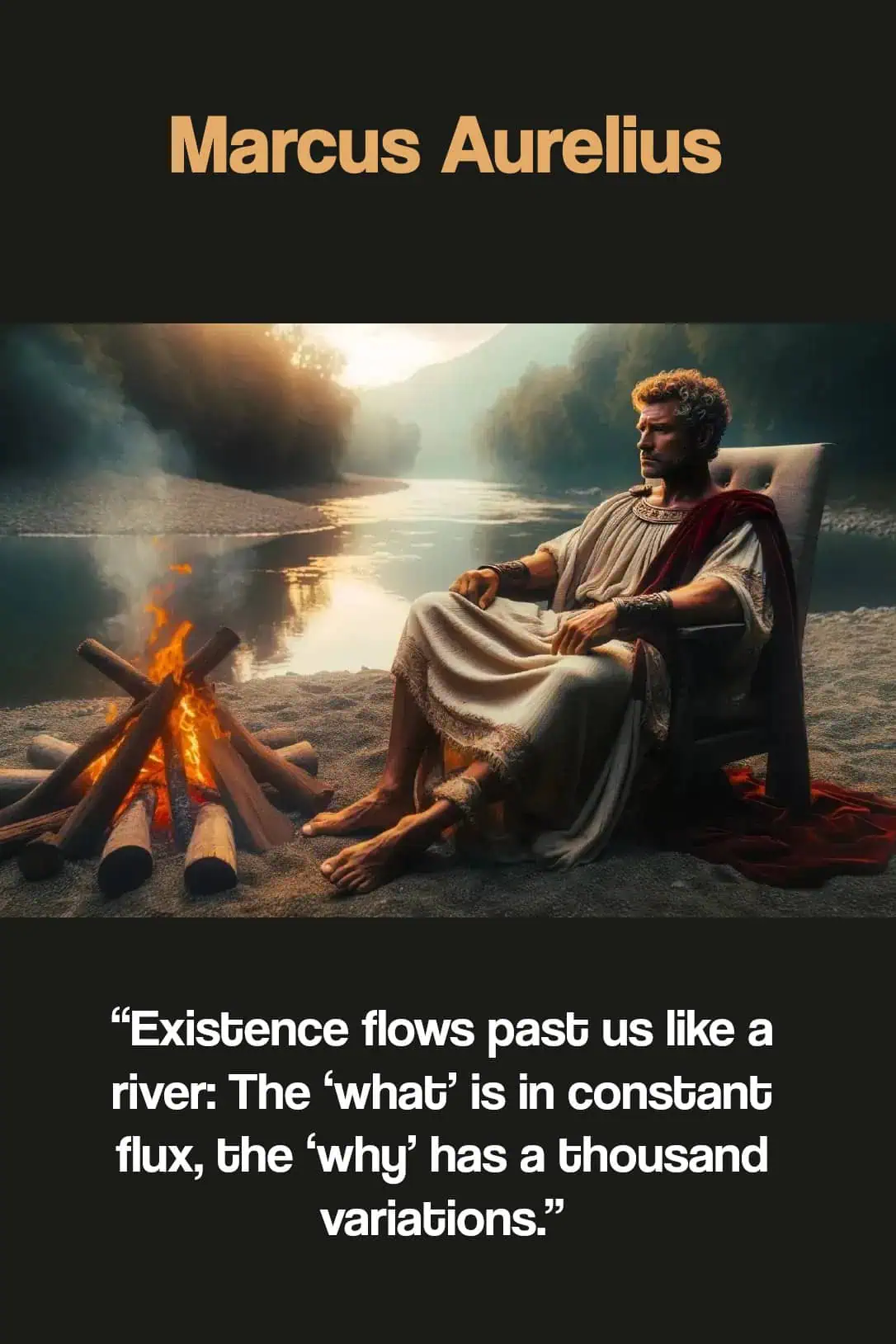

The best-known Marcus Aurelius quote on happiness is this:

“The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts, therefore guard accordingly; and take care that you entertain no notions unsuitable to virtue and reasonable nature.”

— Conversation of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, 3.9, (Apology of Tertullian, page 162)

Gregory Hays translates that quote as: “Your ability to control your thoughts—treat it with respect. It’s all that protects your mind from false perceptions—false to your nature, and that of all rational beings. It’s what makes thoughtfulness possible, and affection for other people, and submission to the divine.” — Meditations, 3.9

Marcus says that your happiness depends on what you allow into your mind.

- You will keep your inner peace if you guard your thoughts carefully and see events as they are.

- You will be stressed and unhappy if you attach prejudices or hasty impressions to life events.

Marcus trained his mind on the first pillar of Stoicism, the Dichotomy of Control. It was his first defense against spending time or energy on things outside his control. It also let him discard any thought that lowered his character or pulled him away from his true nature.

You can do the same: Toss away your biases, prejudices, and faulty opinions. Protect your peace.

• “What injures the hive injures the bee.” — Meditations, 6.54 (Gregory Hays translation)

• “What brings no benefit to the hive brings none to the bee.” (Robin Hard translation)

Marcus shows how our happiness connects with the well-being of our community. If society suffers, so do we. A healthy, functioning society supports the happiness of its people, just as a thriving hive supports each bee.

• “Yes, keep on degrading yourself, soul. But soon your chance at dignity will be gone. Everyone gets one life. Yours is almost used up, and instead of treating yourself with respect, you have entrusted your own happiness to the souls of others.” — Meditations, 2.6 (Gregory Hays translation)

• “For the life of every one of us lasts but a moment, and yours is almost done, and yet you have no respect for yourself, and allow your happiness to depend on what passes in the souls of other people.” (Robin Hard translation)

Marcus asks us to stop letting others decide our worth. His “degrading yourself” warns us against living by others’ opinions.

“Your chance at dignity will be gone” is a warning that life is short, and we have only a few chances to shine.

So, stop wasting time chasing other people’s approval or letting others shape our happiness, before life is spent.

• “I was once a fortunate man but at some point fortune abandoned me. But true good fortune is what you make for yourself. Good fortune: good character, good intentions, and good actions.” — Meditations, 5.37 (Hays translation)

• “But the person who is blessed by good fortune is the one who has assigned a good lot to himself, and a good lot consists of this: good dispositions of the soul, good impulses, good actions.” (Robin Hard translation)

Marcus says, luck from circumstances is unpredictable and short-lived. True fortune isn’t luck, but what we create through our choices. Circumstances change, but good character, intentions, and actions are within our control.

He also tells us the formula for lasting happiness: good morals, noble intentions, and upright actions.

• “So other people hurt me? That’s their problem. Their character and actions are not mine. What is done to me is ordained by nature, what I do by my own.” — Meditations, 5.25 (Gregory Hays trans.)

• “Another does me wrong? Let him look to that; he has his own disposition, and his actions are his own. For my part, I presently have what universal nature wills that I should have, and I am doing what my own nature wills that I should do.” (Robin Hard trans.)

Marcus is clear: if someone wrongs you, it’s on them. Their behavior belongs to them.

You lose nothing by not carrying their burden. Obsessing over what they said or did only drains you. Keep your attention on your own actions. Stay true to your values, and let their poor choices be their concern, not yours.

• “Well-being is good luck, or good character. (But what are you doing here, Perceptions? Get back to where you came from, and good riddance. I don’t need you. Yes, I know, it was only force of habit that brought you. No, I’m not angry with you. Just go away.)” — Meditations, 7.17 (Gregory Hays trans.)

• “Happiness (eudaimonia) is a good guardian-spirit (daimon), or ruling centre within. What is this that you are doing, my imagination? Go away in the name of the gods, just as you came; for I have no need of you. But you have come according to your age-old habit. I am not angry with you: only, go away!” (Robin Hard trans.)

Marcus tells his perceptions that he acknowledges their presence but dismisses their influence.

His automatic, unhelpful thoughts may have come from old habits. So he refuses to follow them. Instead, he focuses on maintaining his inner peace.

• “Happiness in life depends on very few conditions; and just because you have resigned any hope of excelling in dialectic and natural philosophy, do not on that account despair of becoming a free man, and one who is modest, concerned for his fellows, and obedient to God; for it is possible to become a wholly god-like man and yet be recognized by nobody.” — Meditations, 7.67 (Robin Hard trans.)

• “Nature did not blend things so inextricably that you can’t draw your own boundaries—place your own well-being in your own hands. It’s quite possible to be a good man without anyone realizing it. Remember that. And this too: you don’t need much to live happily. And just because you’ve abandoned your hopes of becoming a great thinker or scientist, don’t give up on attaining freedom, achieving humility, serving others, obeying God.” (Gregory Hays trans.)

Marcus says happiness doesn’t depend on recognition or titles. Happiness, in fact, requires very little.

Even if you let go of big ambitions, you can still live a free and honorable life. Practice humility, serve others, and hold yourself to high personal standards. That is real success.

• “When you need encouragement, think of the qualities the people around you have: this one’s energy, that one’s modesty, another’s generosity, and so on. Nothing is as encouraging as when virtues are visibly embodied in the people around us, when we’re practically showered with them. It’s good to keep this in mind.” — Meditations, 6.48 (Gregory Hays trans.)

• “When you want to gladden your heart, think of the good qualities of those around you; the energy of one, for instance, the modesty of another, the generosity of a third, and some other quality in another. For there is nothing more heartening than the images of the virtues shining forth in the characters of those around us, and assembled together, so far as possible, in close array. So be sure to keep them ever at hand.” (Robin Hard trans.)

Look for people who are practicing positive qualities to uplift yourself. Motivation can be found in seeing and appreciating the energy, modesty, and generosity of others.

• “The cucumber is bitter? Then throw it out. There are brambles in the path? Then go around them. That’s all you need to know. Nothing more. Don’t demand to know “why such things exist.” Anyone who understands the world will laugh at you, just as a carpenter would if you seemed shocked at finding sawdust in his workshop, or a shoemaker at scraps of leather left over from work.” — Meditations, 8.50 (Gregory Hays trans.)

Marcus Aurelius gives a sharp lesson here: accept what is bitter or painful, and act. This is the principle of Amor fati.

A bitter cucumber? Throw it out. Brambles in the way? Step around them. That’s enough.

Don’t waste time asking why they exist. They exist because Nature exists.

Like scraps in a workshop, difficulties in life are byproducts of Nature’s processes. Complaining about them misses the point.

What matters is how you respond. Use and work with what you have, and move forward without complaints.

• “People try to get away from it all—to the country, to the beach, to the mountains. You always wish that you could too. Which is idiotic: you can get away from it anytime you like. By going within. Nowhere you can go is more peaceful—more free of interruptions—than your own soul. Especially if you have other things to rely on. An instant’s recollection, and there it is: complete tranquility. And by tranquility, I mean a kind of harmony. So keep getting away from it all—like that. Renew yourself. But keep it brief and basic.” — Meditations, 4.3 (Gregory Hays trans.)

• “People seek retreats for themselves in the countryside, by the seashore, in the hills; and you too have made it your habit to long for that above all else. But this is altogether unphilosophical, when it is possible for you to retreat into yourself whenever you please….” (Robin Hard Trans.)

You don’t need to escape to distant places to find peace.

People often dream of retreats to the countryside, beach, or mountains, hoping for relief from daily stress. Marcus sees this as unnecessary. True calm isn’t tied to location. It’s within you.

Your mind can create its own space of quiet and order. You can reach that inner calm space, away from noise and disorder, with even a brief moment of reflection.

Marcus says this kind of inner retreat doesn’t need elaborate travel or special conditions. Do it often and keep it simple. Just a brief, focused pause from the daily grind to self-reflect and renew yourself.

In one of his moments of inner retreat, Marcus mused: “Existence flows past us like a river: The ‘what’ is in constant flux, the ‘why’ has a thousand variations.”

What is happiness for the Stoics?

Stoicism teaches that a happy life begins with moral excellence.

The founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, defined happiness as a smooth flow of life. His successors, Cleanthes and Chrysippus, took forward this definition.

Marcus Aurelius put it simply: “The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts.”

For the Stoics, a happy mind rests on reason and virtue. An ideal life means living in harmony with Nature, staying indifferent to external circumstances, and building friendships with others.

They also explain what often disturbs our happiness:

- Judging people and things

- Clinging to what other people think

- Worrying about how people might judge us

Stoics believe that if we remove the judgment from any fact, it loses its power to upset us.

Say you spill coffee on your favorite shirt. Rather than feel frustrated, you remind yourself it’s just a stain on fabric. This separates the fact from any emotional weight.

As Marcus Aurelius wrote, “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

- Do you feel happy when someone praises you, or unhappy when you get criticized?

- Does your new gadget make you happy, or feel bad when your friend says you made a bad purchase?

Tying your happiness to praise or possessions is unreliable. These depend on opinions and events outside your control.

Instead, aim for a simple and virtuous life. Seek inner peace by focusing on what you can control—your thoughts and actions.

Today, we see happiness as a positive emotion or a good mood that lasts a short time. But the ancient Stoics used the Greek term eudaimonia to describe happiness.

Eudaimonia does not exactly translate as happiness, but rather as a long-lasting positive emotion. It is how a person feels about their entire life up to that point.

An eudaimonic life is both rewarding and satisfying.

Final Words

Throughout Meditations, Marcus Aurelius reiterates, almost obsessively, the idea that everyone ultimately shares the same destiny in this short life: death.

“Human lives are brief and trivial. Yesterday a blob of semen; tomorrow embalming fluid, ash. To pass through this brief life as nature demands. To give it up without complaint. Like an olive that ripens and falls.”

To be happy, Marcus Aurelius says that we must let go of our judgments about other people and external events, and accept them for what they are. A simple formula he holds is:

“Accept without arrogance, relinquish without a struggle.” — Meditations, 8.33. Robin Hard trans.

Stoics, like Epicureans, believed that the quality of life, rather than the length of life, was more important. They felt that pursuing virtue (and hence happiness) was preferable to living a long life.

Finally, here’s what Marcus might have said to you if he saw you trying to please a narcissist:

“Do you want praise from a man who curses himself three times an hour? Do you want to please a man who is unable to please himself? Or can a man be said to please himself if he regrets nearly everything that he does?” — Meditations, 8.53

√ Also Read: “Death Smiles At Us”: 5 Stoic Lessons To Live By

√ Please spread the word if you found this helpful.