— Researched and written by Dr. Sandip Roy.

The first question about Stoicism and happiness is often this: Are Stoics even happy?

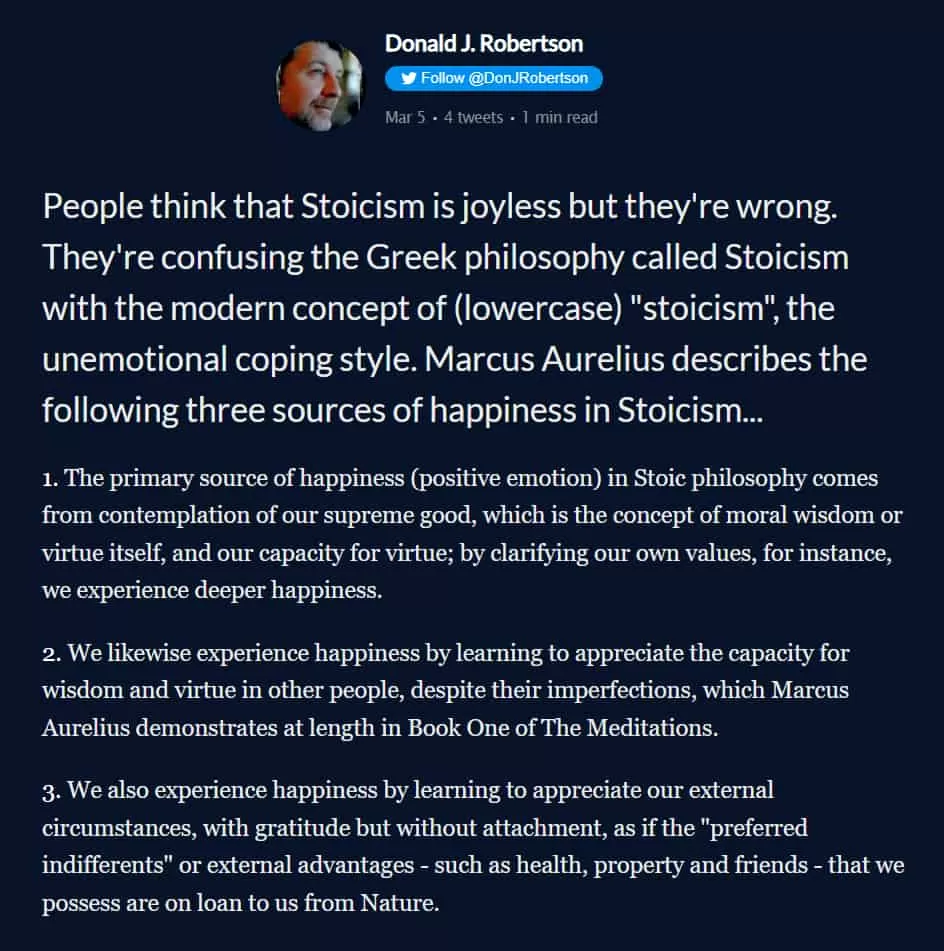

That question comes from the dictionary meaning of stoic (with the small ‘s’) — an expressionless, long-suffering, and resigned person or attitude.

However, the Stoics (with the capital ‘S’) are not people free from passions or devoid of emotions, as many around the world terribly misunderstand them to be.

Stoicism is a practical philosophy that wears its heart on its sleeve: helping people live their best lives.

Are Stoics Happy?

Can Stoics be happy?

Yes, the Stoics can not only be happy but also feel the full range of emotions. Stoicism does not impose a lack of humor and passion, so a Stoic can be happy, sad, angry, or intense, and not hide behind expressionless faces. Stoic happiness is the quintessence of living a good and meaningful life, rather than one of pleasure.

Stoic happiness is being open to experiencing all human emotions, as they are guided by laws of nature, yet choosing not to become overwhelmed by any of them.

Stoic life is about mastering their passions and reaching a state of apatheia, rather than denying or discarding their natural emotions and desires.

In the words of Epictetus, the Stoic sage may be “sick and yet happy, in peril and yet happy, dying and yet happy, in exile and happy, in disgrace and happy.”

In all probability, a Stoic lives a happier life than the rest of us.

Stoicism And Happiness: 4 Principles

The four anchoring factors of happiness in Stoicism are:

- Living in harmony with nature,

- Practicing virtue whatever the cost,

- Being rational to the best of their ability,

- Exercising control and calm indifference towards outside events.

Among those, the one principle that is of utmost importance to a Stoic is practicing virtue.

For Stoics, happiness is a by-product of practicing virtue.

They firmly believe that being a good, virtuous person is both essential and enough to have a happy life.

“A good character is the only guarantee of everlasting, carefree happiness. Even if some obstacle to this comes on the scene, its appearance is only to be compared to that of clouds which drift in front of the sun without ever defeating its light.”

— Seneca (Letter to Lucilius XXVII)

A Stoic Guide To Happiness: 7 Stoic Strategies To Be Happier

Stoic philosophy is more about doing than talking. As Seneca writes in Moral Letter to Lucilius, 20.2,

“Philosophy teaches us to act, not to speak; it exacts of every man that he should live according to his own standards, that his life should not be out of harmony with his words, and that, further, his inner life should be of one hue and not out of harmony with his activities.”

Anyone can achieve a happy state of being if they take a leaf or two out of a Stoic’s playbook of exercises.

I have tried to do that here: gather a set of practical instructions (strategies, if you may) for a happier life from the Stoic philosophers. To form a habit of happiness and equanimity, choose from these the ones you want to adopt.

Here are 7 step-by-step strategies from Stoicism to a happier life:

1. Release the urge to control others; try to control your own thoughts and actions.

Much of our unhappiness results from:

- thinking that we have control over our lives and

- trying to exercise that control over all we engage with, while

- not realizing that we do not and cannot control most parts of our life.

To be happy, the Stoics say, we should focus on what we can control: our thoughts, judgments, and actions.

With these in rein, we can go on to create good values for others and a good life for ourselves.

Epictetus, the Stoic sage who was a slave for most of his early life, argued:

- we don’t have any control over what happens to us,

- we don’t have control over what people around us say or do, and

- we don’t have control of our own bodies, which get sick and old, and eventually, die without any thought about how much we love them.

However, when things happen, we rush to make immediate judgments about them. And when we judge a thing as terrible or bad, then we tend to get upset, build a grudge, and become sad, or angry.

Similarly, if we guess or pre-judge that something bad is likely to happen to us, we get fearful, stressed, and anxious.

So, what creates unhappiness in us is the dark-colored judgments that we attach to events. While the events themselves are, in fact, colorless.

We suffer more in imagination than in reality.

— Seneca

On this, Epictetus said: “It’s not things that upset us, but how we think about things.”

A slightly different translation of the words of Epictetus, which he wrote in the everyday language of Koine Greek, would be this: “Man is disturbed not by things, but by the views he takes of them.”

At the base level, these negative emotions have sprung from the judgments we made about them. So, the things in themselves are empty of positive or negative values. It is what we make of them that creates positive or negative valence in us.

What would seem a catastrophe at the time may turn out to be insignificant later on.

With time, we might even find these incidents happened for our good.

The judgments we make attach values to them, and then those value judgments create our emotional responses.

These value judgments, therefore, are the only things we have control over. Things that happen are not inherently good or bad, but it is within our power to decide how we see them.

And when we see them in a negative light, we get anxious and stressed.

“Today I escaped from anxiety. Or no, I discarded it, because it was within me, in my own perceptions — not outside.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

We have no control over our circumstances, but we do have control over how we react to them.

We have no influence over how external events will unfold, but we do have complete control over our own opinions and judgments about everything. It is one of the six Paradoxes of Stoicism.

So, this is how you invite Stoic happiness into your life:

- Realize that the only thing you have control over is what you think and what judgments you make about others and situations.

- Train yourself to go after only what you control, and give up trying to control things outside yourself, and do this as often as you can.

As you go about your day today, bear in mind that you cannot control anything that is not of your own making; they are events controlled by external factors.

But, all the same, you can control what you think about them.

This marks the difference between unhappiness and happiness.

Letting go of our vain attempts to control the outside world would release a lot of our unhappiness.

Our serenity and stability result from our choices and judgment, not our environment.

— Stoic Wisdom

2. Focus on the process of your action, not on its expected or real results.

Your five-year projection is mostly made up of gas. Your cushy retirement goal is a couch in the clouds that you can’t sit on right now.

A goal is actually a pie in the sky.

Once you set a goal, a slew of external factors may conspire to derail it.

We can start with hope, optimism, and a positive mindset about achieving our goals, but we can never be completely certain of what awaits us in the end.

While we are better off giving up our desires to influence events, we must not lose sight of the task at hand.

The Stoics suggest we work on our project with passion and devotion to the process. We may expect a certain outcome, but we must never become emotionally invested in the result.

When we apply our thoughts and actions to the process of our tasks, we can have the greatest degree of control. When we concentrate on the process well, we can master all the parts of the entire task.

The immediate goal of focusing on the process is within our full control. Once we convincingly see that we can control our actions and nothing more, we gain a decisive vantage over the volatility of our emotions.

So, rather than focusing on the outcome, focus on the process.

While this does not guarantee that we will always reach our targets as we wanted, it does increase the likelihood of finding our way there more often.

Even when we get caught in circumstances beyond our control, the Stoics remind us, we still have the freedom to choose how to see it and how to respond. And our only response should be an action based on rationality and virtue.

Seneca says, in his On The Shortness of Life,

“The greatest obstacle to living is expectancy, which hangs upon tomorrow and loses today. You are arranging what lies in Fortune’s control, and abandoning what lies in yours. What are you looking at? To what goal are you straining? The whole future lies in uncertainty: live immediately.”

Stoics advise us to focus on carrying out action the best that we can, whatever we are into, purely for the satisfaction of doing it well, with no thought for future rewards.

And while focusing on a specific action, a Stoic person eliminates all unnecessary tasks that steal their attention.

That method of intense focus while removing all distractions results in what we know today as Deep Work, made famous by Cal Newport.

If you seek tranquility, do less. Or (more accurately) do what’s essential. Do less, (do) better. Because most of what we do or say is not essential. If you can eliminate it, you’ll have more tranquility. But to eliminate the necessary actions, we need to eliminate unnecessary assumptions as well.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

And that ambition of completely, exclusively, and sharply focusing on the work we choose to do, from start to finish, will remarkably change your happiness for the better.

For focused action, a Stoic never reacts immediately after feeling a negative emotion. They wait so that they do get devoured by the emotion.

As Donald Robertson in his book Stoicism And The Art of Happiness says:

“A brave man isn’t someone who doesn’t experience any trace of fear whatsoever, but someone who acts courageously despite feeling anxiety.”

The Stoic discipline of action is threefold: guarding ourselves against acting impulsively, being mindful of our actions, and remaining detached from the results of our actions.

3. Accept the result, whether it matches your goal or turns out a failure.

There could only be misery if one tried to control things beyond human control.

While the Stoics argued that events in the natural world were beyond one’s control, like floods, diseases, and death, they advised one can only do good at accepting them.

There is a nuance in the Stoic acceptance.

It doesn’t imply that we turn fatalistic and become passive in our future efforts. It means we feel the emotions the negative results bring, then brace ourselves to endure and overcome them.

Moreover, as we said above, Stoics expect a certain outcome from their work but do not become emotionally invested in their final result.

For a Stoic person, everything that happens had to happen. Their love for destiny is called Amor fati.

The Stoics believe the cosmos programs all the events that occur. Because of this, pre-existing causes make events happen and prevent all other alternatives from happening.

Our joy lies in willingly conforming to this preordained plan of the universe.

A Stoic person would advise, “Accept everything which happens, even if it seems disagreeable, since it leads to this, the health of the universe.”

For Epictetus, all external events are fate’s play and are thus beyond our control. It’s only reasonable that we accept whatever happens calmly and dispassionately. As he put it:

“Don’t seek to have events happen as you wish, but wish them to happen as they do happen, and all will be well with you.”

— Epictetus

On this, Seneca said:

“We are more often frightened than hurt; and we suffer more in imagination than in reality.”

— Seneca

Marcus Aurelius wrote,

“Accept things to which fate binds you, and love the people with whom fate brings you together, but do so with all your heart.”

— Marcus Aurelius

A related Stoic strategy is to remind ourselves that whatever happens does not have to suit our desires. The universe works on its own, and it does not need to function to benefit us.

Given this, how can we expect the universe to deliver whatever we might want?

We may think the universe is working against us, but in fact, it has too much work to do than smoothen out the logjams in the way of our success and happiness.

The cosmos keeps moving as it wants, without caring much about us, as we are too minuscule in its grand design of things.

So, wouldn’t it be far better to accept what comes our way? We cannot change what the cosmos has predetermined to happen, but we can choose to accept the result calmly, whatever it is.

What are we, if not just specks of moments in the whole stretch from antiquity to infinity?

Once again, we call up Marcus Aurelius:

Time is a sort of river of passing events, and strong is its current; no sooner is a thing brought to sight than it is swept by and another takes its place, and this too will be swept away.

— Marcus Aurelius

The Stoics practiced memento mori, a reminder of death and the shortness of life.

4. Do not react overtly to criticism, nor let it tie you down to a status quo.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus expended his boyhood and adolescence in Rome as a slave.

He spent days in and days out doing just what he was told to do, and getting punished severely for the smallest of mistakes.

Such a life can shut down the rational, thinking part of the brain. Anyone else in his place might have let their minds slip into a non-functional state.

But not Epictetus. He fought the status quo every day and kept his mind vibrant with deep thoughts of philosophy.

Once, his master Epaphroditus began twisting his leg for amusement. Epictetus told him, “If you go on, you will break my leg.”

But Epaphroditus kept twisting. Finally, when his leg broke, Epictetus uttered through his pain, with unruffled serenity, “Did I not tell you that you would break my leg?”

That was the hallmark of a Stoic: staying unperturbed in mind by the things they cannot control.

Epictetus asks, penetratingly, “If a person gave your body to any stranger he met on his way, you would certainly be angry. And do you feel no shame in handing over your own mind to be confused and mystified by anyone who happens to verbally attack you?”

And this is what he meant: We would react with anger and desperation if anyone were to capture us and make us serve as slaves. Then how come we let our minds serve as slaves to other people’s whims and orders several times a day?

When people around us do or say things to us that make us react, it means they have invaded and enslaved our minds. We argue with them, trying to prove they are wrong. We spend days and hours finding ways to put them down.

They have shackled our mind to a pole, and now our mind scampers restlessly around the same confined area of thoughts, over and over, without freedom.

We forget we have a choice to set our mind free so that it finds peace and solace.

A Stoic person always holds that for a thing to be good, it must be of benefit to us. And the only thing that always benefits us is a calm and rational mind.

No matter what annoyance anyone brings to our doorstep, we have a choice to save our minds from being chained to it.

• However, history is thankful to Epaphroditus because, even though a cruel master, he allowed Epictetus to attend the lectures of Musonius Rufus, a distinguished teacher of Stoicism. And, in time, he let Epictetus go free.

If evil be spoken of you and it be true, correct yourself, if it be a lie, laugh at it.

— Epictetus

5. Feel truly grateful for all the good that you own and were given.

We tire and burn ourselves out when we constantly yearn for things we don’t have.

The desire for earthly possessions is an endless run on an invisible treadmill. It satisfies us for as long as it takes to get used to a new toy.

Once there, we start our sprint for the next goalpost.

Then there is this terrible trait of a narcissist — they find it extremely hard to feel grateful for any favor done or any gift given to them.

Their attitude is as if they were entitled to the good things they received. Stuck in their selfishness, they feel offended when people don’t do things for them.

Those are not rational ways to reach happiness.

A far more meaningful way is to feel grateful for the things we already have right now. It’s much wiser to be full of praise for the many blessings we have in our life.

Seneca’s short and crisp sentence on this was, “Nothing is more honorable than a grateful heart.”

“He is a wise man who does not grieve for the things which he has not, but rejoices for those which he has.”

— Epictetus

Seneca warned us:

“No person has the power to have everything they want, but it is within their power not to want what they don’t have, and to cheerfully put to good use what they do have.”

— Seneca

Even research says running on the hedonic treadmill is an ineffective strategy to make ourselves happier.

The following is an effective Stoic exercise to have a heartfelt sense of deep gratitude for every good thing in our life.

• The simple exercise is to imagine our lives without some of the things that we take for granted — a house, a spouse, food on the table, a table to work upon, eyes to see, hands to work, legs to walk.

Our daily grind makes us forget the value of simple pleasures in life, such as being alive to see another day, family, pets, and friends, and the ability to love and laugh. We lose focus of them by getting fixated on what we do not own yet.

Asking ourselves, “What would my life be without these?” would make us more conscious of those things we take for granted.

Then it gets easy to feel thankful for and appreciative of all that we have in our life. Avoiding setting our targets on the things we lack, and instead, being happy with our blessings, is a sign of wisdom to a Stoic person.

Marcus Aurelius, the Philosopher King, told us that we should occasionally imagine how our lives would be if we did not have the people and the comforts we have now. How much would we crave to have them in our life?

That mental exercise will make things easier to start the habit of not treating them lightly anymore.

Marcus advises himself,

“Do not indulge in dreams of having what you have not, but reckon up the chief of the blessings you do possess, and then thankfully remember how you would crave for them if they were not yours.”

— Marcus Aurelius, The Philosopher King

Again, Marcus Aurelius writes,

“Take full account of what excellencies you possess, and in gratitude remember how you would hanker after them, if you had them not.”

— Marcus Aurelius

The science of positive psychology also supports this: Counting our blessings and appreciating what we have increases our happiness levels.

6. Avoid becoming overwhelmed by emotions that cause you to lose control.

Did you know that the Stoics recognized early on that the longer you let your anger brew, the stronger and more ferocious it becomes?

The Stoics believe we are in complete control over only two things in this life: our thoughts and our actions. The rest is out of our hands.

So, what is the point of wasting time and effort complaining about things that other people do, and the events that happen in the world outside? We do not have any influence over them.

For one, emotions such as anger and envy are not always without any purpose.

Anger may help us assert authority and thwart violence, and envy may propel us to work harder. In fact, in times of injustice and procrastination, they motivate us to take positive action.

However, looking closely, we would find there are far too many times when these emotions serve to only increase our stress.

The next time you feel enraged at any frustrating situation or anyone’s dorky action, you could ask yourself, “Is this anger rational or nonsensical? Would it serve a useful or futile purpose?”

And you might get answers from yourself that may help dilute away your anger.

We are not the governors of other people’s emotions.

The crux is that we cannot command other people into feeling a certain way for us.

We cannot control what thoughts they think, even after we have given them clear directions.

And we can never accurately predict what action they will take as a result of the emotions triggered by those thoughts.

So, after we have determined what is beyond our control, we must actively strive to give up even our pretense of control over them.

Epictetus, in Discourses, says of this:

“Keep this thought at the ready at daybreak, and through the day and night — there is only one path to happiness, and that is in giving up all outside of your sphere of choice, regarding nothing else as your possession, surrendering all else to God and Fortune.”

While letting go of your emotional attachments, also remember that you only have the power to control your attitude and actions, and nothing more.

Accepting and exercising this, instead of frittering away our time worrying about things outside ourselves, will make us more productive and satisfied.

On this, Marcus Aurelius says,

“The cucumber is bitter? Then throw it out. There are brambles in the path? Then go around them. That’s all you need to know. Nothing more. Don’t demand to know “why such things exist.” Anyone who understands the world will laugh at you, just as a carpenter would if you seemed shocked at finding sawdust in his workshop, or a shoemaker at scraps of leather left over from work.”

— Marcus Aurelius (Meditations, 8.50)

And so, as the Stoic person will advise you to:

- stop heeding much of what others say and do,

- focus only on your thoughts, actions, and task processes,

- list every day what you really control and what you don’t,

- remind yourself to focus on the former and ignore the latter.

Withdraw from those things that you do not control, and focus only on what is in your control, that is, what is inside you, and you will find yourself free, happy, and undisturbed.

Contemplate these words by Epictetus as you go about your day,

“There is only one way to happiness, and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond our control.”

7. Be fully aware and mindful of the present moment.

A Stoic person carries this knowledge everywhere they go: all happiness lies in the present. On this, Seneca advises,

“Every day as it comes should be welcomed and reduced forthwith into our own possession as if it were the finest day imaginable.”

— Seneca

Because thoughts about the future are loaded with worries and anxieties. And tresses and regrets get towed along by our thoughts about the past.

To be happy and free, a Stoic person chooses to spend most of their time in the present moment.

Standing in and acting from the present, we understand a worrying mind never changes the future for anyone. We also realize no one ever gets the promise of a perfect future.

When in the present moment, we do not worry about whether the plans and dreams of tomorrow will come to fruition or not.

The whole future lies in uncertainty: live immediately.

— Seneca

When in the present, we do not try to rewrite our history.

With our feet firmly planted in the present moment, we do not run in endless loops over things from the past that we could have done differently. We do not get trapped in a mire of regret, resentment, and bitterness.

Once we are away from disturbing thoughts about the future and the past, we find calmness and peace. It is then that we can focus fully on the work at hand.

We often refer to the conscious practice of mooring ourselves in the present as mindfulness.

And when we immerse ourselves into our work, we attain a state when we forget the surroundings and time, and even our hunger and thirst. This is a state that the Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called Flow (The Psychology of Optimal Experience).

Flow is the state of “optimal experience”—one that makes us reach a level of high satisfaction.

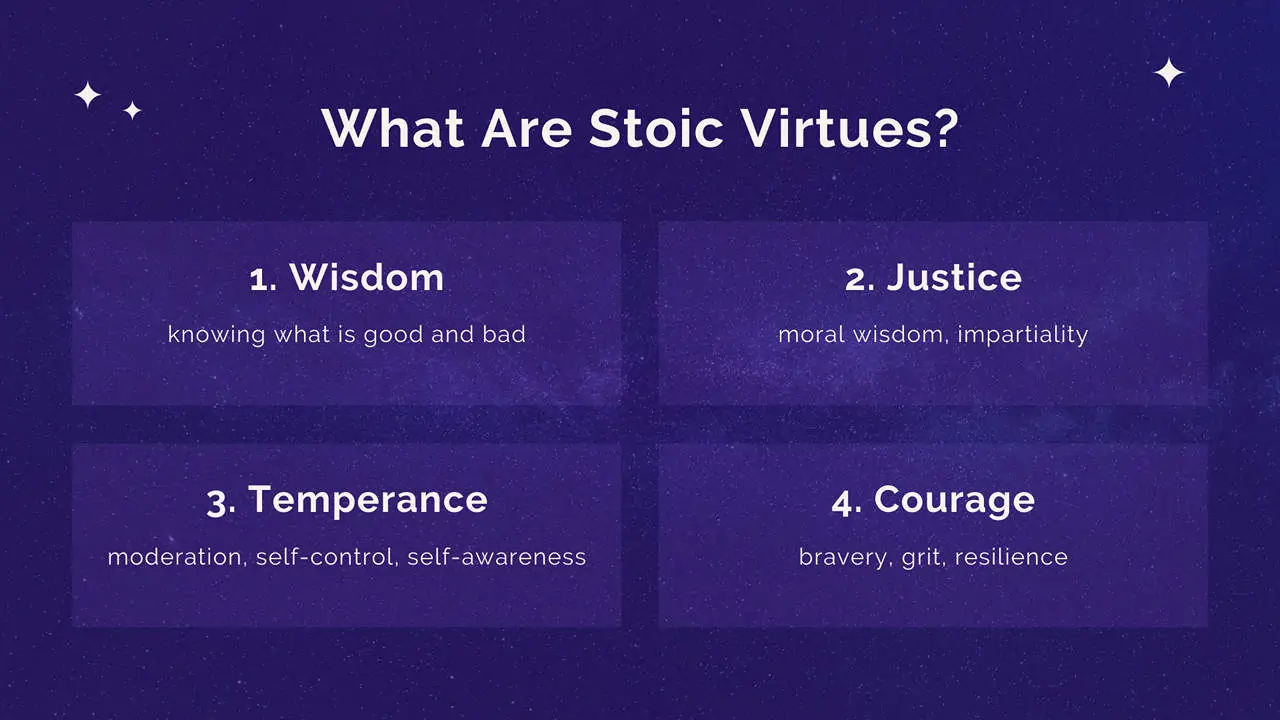

The four cardinal virtues of Stoicism—Wisdom, Justice, Temperance, and Courage—can help you live your best possible life.

We are living in a time of great upheaval. In this post-pandemic world, we are anxious about the future like never.

As we project ourselves into the future, we do not see things clearly or surely. We fear that our goals and dreams may lie shattered.

In times like these, a Stoic person would be more headstrong about living in the reality of the here and now.

They would be happy to wake up to a new morning, find enough to eat and share with their close ones, and end the day with a night of peaceful sleep.

They would have asked,

What do you achieve by fixating on a future that is always unknown and unpredictable? Instead, why not accept each day as a wondrous gift and live it with a sense of gratitude and “awe”?

Does Stoic happiness hold against psychology?

According to Positive Psychology, what many call the Science of Happiness, happiness, or well-being is both positive feelings, pleasure, and joy (hedonic well-being or subjective well-being, SWB) as well as meaning, purpose, and life satisfaction (psychological well-being or eudaimonic well-being, EWB).

However, Kashdan, Biswas-Diener, and King suggest hedonic and eudaimonic well-being overlap conceptually and may have mechanisms that operate together. The authors write:

“When Aristotle proposed the distinction between eudaimonia and hedonism, he rejected the pursuit of pleasure, per se, suggesting that human beings ought to listen to a higher calling of a life of virtue. Yet, Aristotle also noted that eudaimonia was the most pleasant of human experiences. Years of research on the psychology of well-being have demonstrated that often human beings are happiest when they are engaged in meaningful pursuits and virtuous activities.”

— Kashdan, Biswas-Diener, King (Reconsidering happiness)

One of the groundbreaking findings from the field is that the pursuit of happiness makes us unhappy. People who value happiness highly are likely to have worse overall well-being, more depressive symptoms, and a lower ratio of positive to negative emotions.

It is something that agrees with the spirit of Stoicism, which asserts instead of running after happiness, if we choose to live virtuously, a good life will follow.

Before exploring how you too can achieve the Stoic state of happiness, here is a surprising fact: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the leading evidence-based form of psychotherapy in use today for treating anxiety and depression, is indebted to Stoicism.

Both Stoicism and CBT insist emotions arise mainly from our beliefs and thoughts. Both recommend that we can get the better of our emotional upheavals by changing our beliefs.

Chrysippus contended that a philosopher’s role should be that of a “physician of the soul,” which we can safely interpret now as a psychotherapist.

Stoicism’s Keystone of Happiness: Virtue

How do the Stoics stay happy?

The Stoics stay happy by the strength of their belief that the key source of happiness is virtue or arete. To the Stoics, moral virtues lay down the foundation of a happy life. They assert one should constantly strive to practice virtue and do the right thing for a happier life, even if one were to fail occasionally.

For a Stoic, happiness is a by-product of virtuousness.

The Stoics also teach that nothing is inherently good or bad, but it is our judgment that makes it so. We often tend to make snap judgments about people and circumstances that rob us of our peace. Epictetus said of this,

“Man is affected not by events but by the view he takes of them. We should always be asking ourselves: Is this something that is, or is not, in my control? The essence of philosophy is that we should live so that our happiness depends as little as possible on external causes.”

— Epictetus (The Enchiridion)

A peaceful mind, the Stoic hold, comes from an ability to stay open-minded and non-judgmental about ourselves and others around us.

Of course, it takes vast amounts of practice and self-discipline to hold back one’s judgment and prejudice against a tug of emotions. But you can learn it through the practice of Stoic exercises.

“A good character is the only guarantee of everlasting, carefree happiness. Even if some obstacle to this comes on the scene, its appearance is only to be compared to that of clouds which drift in front of the sun without ever defeating its light.”

— Seneca (Letter to Lucilius XXVII)

Books On Stoicism And Happiness

- A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy by William B. Irvine

- A Field Guide to a Happy Life: 53 Brief Lessons for Living by Massimo Pigliucci

- Stoicism and The Art of Happiness: Practical Wisdom for Everyday Life by Donald Robertson

- Does Happiness Write Blank Pages? On Stoicism and Artistic Creativity by Piotr Stankiewicz

- On the Happy Life (Illustrated): De Vita Beata by Seneca—Translation by Aubrey Stewart

- The Good Life Handbook: Epictetus’ Enchiridion (Stoicism in Plain English) by Chuck Chakrapani

- Happy: Why More or Less Everything Is Absolutely Fine by Derren Brown

Final Words

The Stoic way of happiness is to live virtuously, mindfully, and naturally, with control over our thoughts and actions.

Life is barely long enough to do all the great things you want to do. You may realize this if you have a 50-item bucket list that still has a bunch of items that remain undone year after year.

We are never certain how much time we are left with on this planet, so where’s the time to waste?

Start now. As Epictetus would have told you, “From now on, then, resolve to live as a grown-up who is making progress.”

From time to time, in a day, the Stoics reminded themselves of death. This made them sharply aware of the shortness of life and led them to not waste their time on trivial things.

So, start living your greatest moments today onward and make your future self the best possible version of yourself. Seneca warned us: “Whatever time has passed is owned by death.”

√ Please share it with someone if you found this helpful.

√ Also Read: Stoic Blueprint for A Life You Would Want To Live Again

• Our Story!