Today's Monday • 23 mins read

— By Dr. Sandip Roy.

Any philosopher worth their salt has these two basic questions to understand and answer:

- What is the highest good in life?

- What should a person ideally aim for in their life?

The Stoic philosophers answer both with a single word: virtue. To be an excellent human being means practicing virtue in thoughts and actions.

Many of us wonder if we’re living a life we’ll be proud of. Would we choose to live the same way again if given the chance?

Stoicism, founded in Athens in 301 BCE, offers practical wisdom for that exact question.

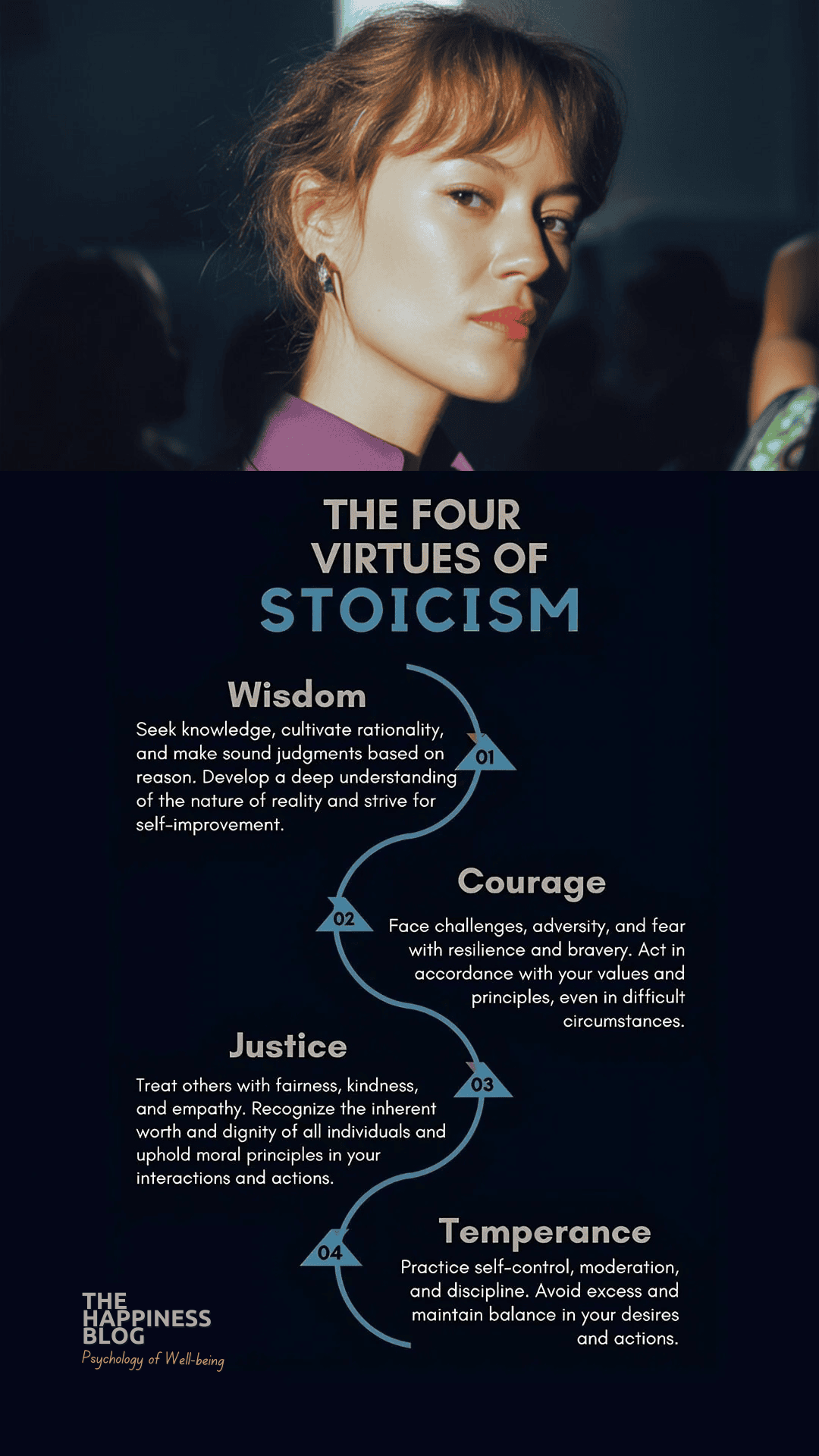

This ancient yet modern philosophy centers on four cardinal virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. Embracing them in our daily lives, we can build a life without regrets.

4 Stoic Virtues: Wisdom, Justice, Temperance, Courage.

Stoicism teaches four main virtues that guide a good life:

- Wisdom (Phronêsis) – This is the skill of knowing what is good, what is bad, and what is neither. Wisdom lets us see things clearly and make choices based on facts, not fears, biases, or wishes. It guides us to take purposeful actions that prevent future harm.

- Justice (Dikaiosynê) – Fair treatment of others and ourselves. It means being kind, honest, and respectful of others. Justice in Stoicism is about being beneficial to society and acting in a morally right way, remembering that we are part of something larger than ourselves.

- Temperance (Sôphrosynê) – Self-control in all things. Also called moderation, temperance helps us find the middle path between too much and too little. It builds self-awareness and self-discipline, and prevents harmful excess and maintains social decorum.

- Courage (Andreia) – Facing difficulty with strength. Courage isn’t fearlessness but acting despite fear. It means bravely standing by our values even when it’s hard. It’s the moral and mental strength to handle difficulties and show resilience without sacrificing our values.

Together, these four virtues create what Stoics call Aretê or Virtue — excellence of character.

The early and middle Stoic eras were marked by wars, diseases, brutal rulers, and food shortages. These virtues helped them live fulfilling lives, undefeated by life’s trials.

Today, we face different challenges, like information overload, social media pressure, climate change, and rapid technological shifts. Interestingly, these same virtues can help us cope with issues of our modern world with strength and clarity.

Cicero, one of the most renowned orators of ancient Rome, explains the four cardinal virtues thus:

Virtue is a habit of the mind, consistent with nature, and moderation, and reason. … It has then four divisions — prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Prudence is the knowledge of things which are good, or bad, or neither good nor bad. … Justice is a habit of the mind which attributes its proper dignity to everything, preserving a due regard to the general welfare. … Fortitude [i.e., courage] is a deliberate encountering of danger and enduring of labour. … [And] temperance is the form and well-regulated dominion of reason over lust and other improper affections of the mind.

— Cicero, De Inventione (II.53-54)

Let’s go into the details of each Stoic virtue:

1. Wisdom or Phronêsis: The Compass of A Happy Life

Being wise means being able to make fair choices.

Phronêsis is wisdom or prudence – the practical ability to analyze and navigate the complexities of life, separating the good from the bad and the neutral (indifferent to human life).

In the 3rd century book Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius says that wisdom is the “knowledge of what should and should not be done, or knowledge of what is good or bad or neither.”

Wisdom is an internal compass that directs your decisions and actions towards eudaimonia, or human flourishing. This inner guide helps you filter out the substandard from the high-standard, and make choices that would eventually prove excellent.

“A venerable tradition in philosophy, associated primarily with Aristotle and Plato, maintains that having knowledge is virtuous, while ignorance is a vice. Accordingly, no trait can be a virtue if having that trait requires being ignorant of certain facts.”

— David Shatz, Professor of Philosophy, Ethics, and Religious Thought, Yeshiva University

This is how wisdom helps us achieve personal peace, joy, and happy life away from suffering:

- Most of our challenges often stem from misguided beliefs rather than our circumstances. Wisdom empowers us to reassess those beliefs, accept the past, and forge a renewed self.

- It enables us to distinguish between dubious choices and virtuous ones, between justice and injustice, and to differentiate genuine pride from hubris, thus allowing us to stop overthinking.

- Wisdom also helps us stay calm during arguments and disagreements.

Seneca said, “Without wisdom the mind is sick, and the body itself, however physically powerful, can only have the kind of strength that is found in a person in a demented or delirious state.”

Massimo Pigliucci, a modern proponent of Stoicism, the Professor of Philosophy at the City College, New York, and author of The Stoic Guide to a Happy Life: 53 Brief Lessons for Living says:

“The reason why virtue/wisdom is the only good thing because, by definition, it cannot be used to do bad. A wise person is the one that takes the right course of action, not just instrumentally, but morally. A wise villain, by contrast, is an oxymoron.”

Wisdom in Stoicism means being careful and thoughtful, making good decisions, thinking quickly, being practical, having a clear idea of what you want to do, and being resourceful.

Can you, or I, live without getting criticism or negative comments? No. Even when we’re doing everything right, there will be faultfinders.

This is how we can use the power of wisdom to handle criticism and negative people:

- If we see there’s truth in the criticism, we acknowledge it and adapt accordingly.

- If there’s no truth, we ignore their words and confidently stay on our course.

- Wisdom helps us focus on the message without judging the messenger.

Wisdom stands as a complete virtue in its own right. Some feel that wisdom overlaps with Virtue or Aretê, but Stoic masters keep the four cardinal virtues separate.

And you should commit to memory what the Stoic Emperor Marcus Aurelius told himself daily about the challenge of justice:

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: the people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil.”

2. Justice or Dikaiosynê: Doing The Right Thing At All Times

Being just means treating others fairly and with respect.

Justice or morality means upholding the rights of others and ensuring that everyone gets treated equally. It means doing what is right and fair, and doing it at all times, more so in times of weakness and adversity.

A Stoic believed that justice was their duty to society, and that they should be good-hearted, fair, and honest.

Our sense of justice watches from behind how we act and how we decide when it comes to others in our community. This sense should be steady, equitable, and unselfish.

“If it’s not right, do not do it. If it is not true, do not say it.”

— Marcus Aurelius

Justice includes piety, good-heartedness, public spiritedness, honesty, equity, and fair dealing.

From a Stoic’s standpoint, a just person guides their decisions based on what is fair and gives others their proper dues, even when under threat or in turbulent times. They waste no time choosing what would serve society best.

For the unjust people, the idea of justice shifts from case to case, as they try to balance each situation with how much it is good to them against how much it is unfair that others will tolerate.

“That which is not good for the bee-hive cannot be good for the bees.”

— Marcus Aurelius

People without a sense of moral justice live in mental chaos and moral morass. When faced with a moral dilemma, they must brainstorm to pick an option every time.

The just people, on the other hand, are not mentally drained and lost on willpower. They don’t overanalyze their options, so they can effortlessly make the right call every time.

Justice is like having a sense of fair play inside your heart. It is following the rules of fairness and equity, making sure everyone gets a fair shot.

Justice means giving everyone what they deserve, whether in a game or in life. It’s choosing to do the fair thing because it feels right.

It is the virtue that involves distribution: distributing to each person according to what they deserve.

Musonius Rufus, a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD, best known for being the teacher of Epictetus, said of this:

“To honor equality, to want to do good, and for a person, being human, to not want to harm human beings—this is the most honorable lesson and it makes just people out of those who learn it.”

Marcus Aurelius held Justice as the highest importance of the four Stoic virtues as he reigned over the vast Roman Empire for two decades. He is universally acknowledged as the most just of all emperors of Rome before and after him.

“Your death will be soon on you: and you are not yet… convinced that justice of action is the only wisdom.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Mediations (4.37)

3. Temperance or Sôphrosynê: Balancing Desires And Needs

Being temperate means avoiding extremes and living a balanced life.

Sôphrosynê, also called moderation or temperance, is the Stoic virtue that includes self-restraint, self-discipline, and the mastery of one’s willpower.

It means being mindful of our desires and not letting them control us. And engaging only in what is necessary and essential, not more.

Temperance includes organization, orderliness, modesty, self-control, good discipline, and seemliness.

- This virtue teaches us not to be swayed by extreme emotions—whether it’s excessive joy or sorrow, love or disdain, or praises or grudges.

- Temperance champions the pursuit of long-term well-being over fleeting gratification, and aligns with the Epicurean way of a life of simple pleasures.

- It’s the balanced state that prevents us from overeating, overthinking, or overindulging in life’s temptations.

- Temperance involves thoughtful acquisition, urging us to consider carefully what we should acquire before deciding to acquire it.

Temperance, at the right time and to the right degree, can give us abundance and fulfillment. Let’s turn to the wisdom of Stoic philosophers to shed light on this virtue.

Marcus Aurelius, who was insistent on having temperance and wrote what sets humans apart from animals is their ability to control their impulses, says,

“Most of what we say and do is unnecessary: remove the superfluity, and you will have more time and less bother. So in every case one should prompt oneself: ‘Is this, or is it not, something necessary?’ And the removal of the unnecessary should apply not only to actions but to thoughts also: then no redundant actions either will follow.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 4.24

And Seneca sagely advised in his Letters From A Stoic,

“You ask what is the proper limit to a person’s wealth? First, having what is essential, and second, having what is enough.”

“People who know no self-restraint lead stormy and disordered lives, passing their time in a state of fear commensurate with the injuries they do to others, never able to relax.”

Donald Robertson, a cognitive-behaviorist and a leading Stoic thinker who authored the excellent How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, says,

“Stoics employed it to rise above their fears and desires and achieve apatheia or freedom from unhealthy passions and attachment to external things.”

Temperance or moderation guides us in making wise decisions (“smart choices”) about our desires and pleasures, without excess. It’s like having a personal moderator who lets us savor life’s delights, but never allows irresponsible overindulgence.

A Stoic exercises moderation in all aspects of life, be it wealth, power, hunger, or any form of indulgence. Today, there’s another: doomscrolling until the cows come home.

Temperance can help us moderate this information overload and dopamine addiction by handling our digital engagements with mindfulness and restraint.

“What needs to be taken care of is not let need become greed. Because needs can always be met, but greed can never be fulfilled.”

— Rajnikanth, a highly popular Indian actor

4. Courage or Andreia: Being Brave And Staying Strong Inside

Being courageous means facing our fears and persevering in the face of adversity.

Also called fortitude, the virtue of courage is the state of standing strong and thinking correctly in dangerous and fearful situations. It means standing up for what we believe in, even when it’s difficult.

Courage is not the elimination of fear, desire, or anxiety. Rather, it is deciding and acting despite your fear, passion, and anxiety.

So, being courageous is facing our fears and doing the right things even when shivering in fear.

Courage is subdivided into endurance, confidence, great-heartedness, stout-heartedness, high-mindedness, cheerfulness, and industriousness (love of work).

- Courage is like having an inner shield that keeps you battle-ready, no matter how tough things get. It’s the confidence a soldier feels in war, knowing what to do and how to stay calm.

- Courage means you don’t let fear make your decisions for you; instead, you listen to your inner wisdom. It’s about being brave, even when you might be facing something as scary as death.

- Courage guards your mind and protects your thoughts in tough situations. Its strength helps face danger without backing down, sticking to what you know is right.

- Courage is keeping your cool and holding on to your brave thoughts, even when things get as intense as they do in a battle, and it’s about sticking to the rules of being brave.

The Stoics warned us that courage without other virtues (especially justice and wisdom) stops being a virtue; instead, it becomes a vice. So, you can’t be truly courageous if you’re not also being just, wise, and temperate in your actions.

Courage also touches upon other emotions. Cicero, a skilled orator and politician in the late Roman Republic, said we need courage to deal with excessive desire (cupiditas), pain or grief (aegritudo), immoderate pleasure (voluptas), and anger (iracundia).

Courage is built on endurance and resilience in the face of fear. Once, a student asked Epictetus which words would help a person thrive, and he replied:

“Two words should be committed to memory and obeyed by alternately exhorting and restraining ourselves, words that ensure we lead a mainly blameless and untroubled life: persist and resist.”

Epictetus tells us that without persistence, we cannot endure hardships well, and may give in to sinful vices. And without restraint, we cannot resist the pleasures and give in to overindulgence.

Marcus Aurelius wrote of the virtue of courage,

“So remember this principle when something threatens to cause you pain: the thing itself was no misfortune at all; to endure it and prevail is great good fortune.”

Courage is also about showing indifference to external situations, such as being intrepid in the face of a death threat. (Find out what the Stoics thought of Death.)

This is what Seneca says of this cardinal virtue:

“[Courage] is neither rash bravado nor thrill-seeking nor love of danger. Rather it is a knowledge of how to distinguish between what is bad and what is not. Courage is very careful of its own safety, yet it is also very well able to endure things whose bad appearance is false.”

7 Ways To Practice Stoic Virtues For More Peace In Modern Life

With the four cardinal virtues, your life can be better than that of the “mob.” As Seneca said,

“Let our aim be a way of life not diametrically opposed to, but better than that of the mob.”

This is how you can practice the Stoic virtues for a peaceful life:

- Make Virtue Your Default Value: Embrace virtue (moral excellence) as your core value. Recognize it as the only true good in life and let it guide your decisions, thoughts, and actions consistently. Make it the default way you make decisions in your life.

• This helps you find inner peace, as you don’t have to fight inner battles when you face difficult decisions. You simply ask yourself, “Is it virtuous?” and choose whatever is wise, bold, fair, and temperate. - Control Only What You Can & Be Indifferent To The Rest: Focus on only what’s in your control. In every situation—pain, adversity, temptation, or threat—ask yourself how much of it you can control. Handle these controllable parts with Virtue as best you can. And be indifferent to the rest. As Ryan Holiday says, “A Stoic believes they don’t control the world around them, only how they respond—and that they must always respond with courage, temperance, wisdom, and justice.”

• Being indifferent to things outside your control, like wealth, praise, adversity, and others’ opinions, helps you avoid needless stresses. This focus allows you to direct your mental energy to your reactions to the controllables, which is what truly matters for keeping your peace. - Question Your Actions: Pause before acting or reacting. Use wisdom to answer these: “Is this the best that I am about to do?”, “Is this fair, sensible?”, “Am I maintaining self-control?”, “What would a Stoic like Marcus Aurelius do in my situation?” Then do what Marcus Aurelius suggested, “If it’s not right, do not do it. If it is not true, do not say it.”

• Pausing to reflect before you act helps you see the situation from all sides, giving you clarity, leading to better choices and fewer regrets later on. - Don’t Compromise Your Core Values: Never sell out your core values to wealth, fame, comforts, money, possessions, or expensive things. If you have to choose between virtue and material gain, choose virtue every time. Remember Cicero’s words: “If you possess virtue, you lack nothing necessary for living well. Virtue alone can lead to happiness, honor, and love, regardless of your material possessions.”

• Staying true to your values helps you find peace. You protect your self-respect and feel good about knowing you chose what’s right, not what’s easy. - Practice Temperance In Advance: Occasionally, practice strict moderation to prepare your spirit for life’s unpredictability, as the wealthy Stoics used to do on certain days every year. Eat simply, dress plainly, and speak less. This practice, called Premeditatio Malorum, teaches you that what you once feared isn’t so frightening after all.

• Growing your moderation ‘muscle’ ahead of time lets you see unexpected obstacles as less daunting, keeping you less stressed. You learn that what once seemed frightening isn’t so scary after all. - Be Courageous (Despite Shivering): Do the right thing, even when you are fearful, cold, weak, poor, or overpowered. Even when no one is keeping a watch, when no one can blame you, and when you can get away with it. A true Stoic does what is right simply because it is right. This is their default, and this is what keeps them calm and happy.

• Facing uncomfortable situations, and acting bravely despite feeling scared, builds inner strength and confidence. This gives you peace later, knowing you did what was right, no matter how hard it was. - Accept Fate, But Take Action: This is the concept of amor fati, which means loving your fate. This Stoic idea teaches us to accept everything that happens to us, good or bad, as necessary parts of our journey. Instead of wasting your time or thoughts resisting or resenting it, we are better off focusing on how you can respond positively. Ryan Holiday says, “If it happened, then it was meant to happen, and I am glad that it did when it did. I am meant to make the best of it.”

• By accepting fate, you release yourself from frustration and disappointment, allowing mental space for the growth mindset. This mindset removes the need to regret or worry over “spilt milk”, and nudges you to take meaningful action on the challenge, so you grow out of it.

How To Cultivate Each Stoic Virtue?

Virtuous behavior is indispensable and non-negotiable in a Stoic’s life. Stoics believe that being virtuous means living in harmony with reason and nature. To achieve this, they cultivate the four cardinal virtues in these ways:

- Wisdom: Seek Truth and Learn Continuously: Cultivate wisdom by actively seeking knowledge and understanding. Make sound judgments by learning from experiences and practicing introspection. This pursuit of truth will deepen your self-awareness and enhance your comprehension of the world.

- Courage: Stand Resolute Amidst Adversity: Embrace courage not just as physical bravery but as mental and emotional resilience. Face life’s challenges and fears with unwavering determination, using your rational understanding to guide you through tough times.

- Justice: Act Ethically and Contribute Positively: Be just by treating others with fairness and respect. Recognize your role in society and the interconnectedness of all. Uphold moral values in your actions and strive to make a positive impact on your community.

- Temperance: Balance Desires with Rational Restraint: Practice temperance by controlling impulses and desires. Find the middle ground between indulgence and restraint, and make decisions that reflect your true values. This balance will lead to rational choices that contribute to a well-ordered life.

To a Stoic, the moral sequence leading to happiness in life is this:

If you are virtuous, then you are good, and therefore you will be happy.

So, if a Stoic can be happy, how can we use their ways to be happy?

7 Key Facts About Stoic Virtues

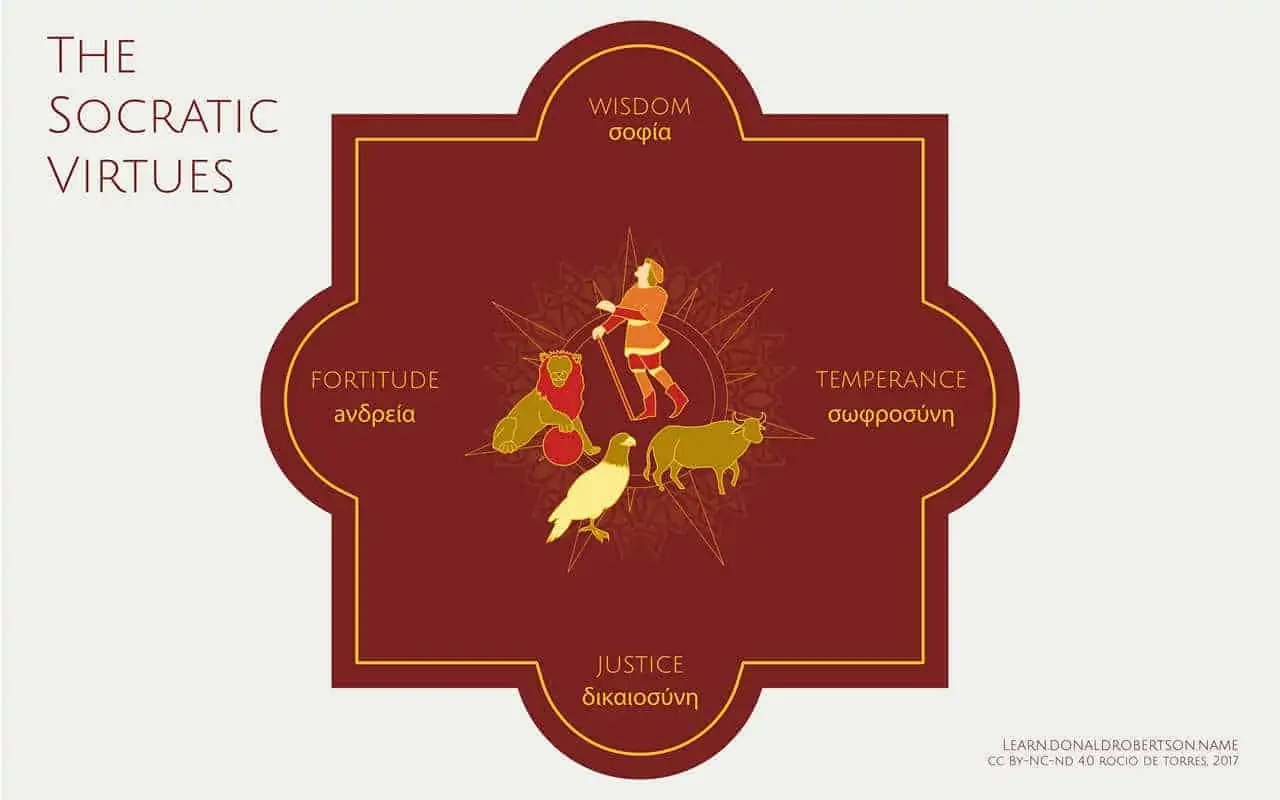

- Ancient Roots: The four virtues come from Socrates and Plato. The Stoics adopted these ideas and built their entire philosophy around them.

- The Highest Good: The ultimate aim in Stoicism is attaining the “highest good” in life, or summum bonum. This is living with moral and ethical excellence.

- Complete Happiness: They say Virtue is both essential and enough for true happiness (what the Greeks called “eudaimonia”). Nothing else, not money, fame, or pleasure, matters as much.

- Facing Problems: Stoics believe that moral excellence in all situations helps us handle any problem. With these four virtues, we can cope well with any challenge.

- Living Together: Practicing virtue creates harmony with others. It builds strong communities and helps us bounce back from hard times.

- Open to Everyone: Everyone can practice virtue. The Stoics taught that everyone has has the right and the capacity to become virtuous, regardless of wealth or status.

- A Learnable Skill: Virtue isn’t a static trait, but it works like a skill. Just like learning an instrument or sport, we can practice and improve our wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance every day.

Stoic Quotes on Virtue

Here are some beautiful quotes on Stoic virtue:

“The fundamental goal (of virtue ethics) is to live a life worth living, a eudaimonic existence, though what this means, precisely, varies from school to school. We achieve this goal by practicing a number of virtues, practical wisdom being the one that teaches us the crucial difference between what is and is not good for us, morally speaking.”

— Massimo Pigliucci

“If, at some point in your life, you should come across anything better than justice, prudence, self-control, courage—than a mind satisfied that it has succeeded in enabling you to act rationally, and satisfied to accept what’s beyond its control—if you find anything better than that, embrace it without reservations—it must be an extraordinary thing indeed—and enjoy it to the full.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 3.6

But if nothing presents itself that’s superior to the spirit that lives within—the one that has subordinated individual desires to itself, that discriminates among impressions, that has broken free of physical temptations, and subordinated itself to the gods, and looks out for human beings’ welfare—if you find that there’s nothing more important or valuable than that, then don’t make room for anything but it.”

Marcus Aurelius explains how to use Virtue to the best of our ability:

“They cannot admire you for intellect. Granted — but there are many other qualities of which you cannot say, ‘but that is not the way I am made’. So display those virtues which are wholly in your own power — integrity, dignity, hard work, self-denial, contentment, frugality, kindness, independence, simplicity, discretion, magnanimity. Do you not see how many virtues you can already display without any excuse of lack of talent or aptitude? And yet you are still content to lag behind.”

— Marcus Aurelius, (Meditations, 5.5)

FAQs

How did the Stoic virtues originate?

Socrates said wisdom is good because it is best if only human abilities are good, and not because wisdom is the only good thing. According to Aristotle, an action counts as virtuous when one chooses the action knowingly and for its own sake. In simple terms, it means virtue shows itself in action.

Aristotle was Plato’s student, and it was Socrates who taught Plato.

In a lighter vein, in Anscombe’s famous phrase, the Stoic virtues were “conjured up by Aristotle.”

How do the Stoics relate to the universe?

They believed that the universe is governed by a rational and benevolent force, which they called Logos. They also believed that each individual has a spark of the divine within them, and that we can all live in harmony with the Logos.

To live in harmony with the Logos, the Stoics believed that we must cultivate the four cardinal virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. And that we must accept what we cannot control, and focus on what we can control.

The Stoics believed that we could achieve eudaimonia (a state of inner peace and tranquility that is not disturbed by external circumstances) by practicing the four cardinal virtues.

“Constantly think of the universe as one living creature, embracing one being and soul; how all is absorbed into the one consciousness of this living creature; how it compasses all things with a single purpose, and how all things work together to cause all that comes to pass, and their wonderful web and texture.” — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 4.40

[Link to download the PDF of the four Stoic virtues]

Final Words

You can be a Stoic and still enjoy life, no matter where you are in life. Some of the most famous Stoics were slaves, senators, water bearers, and emperors who laughed, loved, and lived among us.

As a start, stop being biased in your opinions and outlook, be present while listening to others, treat all with fairness, and exercise discipline.

Let what you do to others be guided by Marcus Aurelius’ “What injures the hive, injures the bee.”

√ Also Read: “Death Smiles At Us”: A Fake Marcus Aurelius Quote With 5 Powerful Stoic Lessons

√ Please share it with someone if you found this helpful.