Reading time: 25 minutes

The ancient Stoics told the greatest story about remembering the shortness of life. Generations have retold that original story through art and culture. It is called memento mori, a call to embrace life fully and mindfully.Approach me, stranger. Nothing in my story

— Michael Coy

should startle you. Your flesh has always known it.

I just remind you. I’m Memento Mori.

In the Middle Ages, tombs and monuments often bore carvings of skulls and skeletons. These figures were memento mori motifs. They reminded the onlookers that they, too, were marked for death.

But the greatest story of memento mori is older, told by the Romans. It traversed time, from the generals, slaves, pharaohs, and philosophers to playwrights, painters, the Grim Reaper, and skull tattoos.

Memento Mori Meaning

“Memento mori” is a Latin phrase that means “Remember, you have to die.” It reminds us of the shortness of life and the randomness of death. The Stoic philosophers of ancient Rome popularized it, asking their followers to use their limited time on earth wisely and live virtuously and mindfully.

A “Memento” is a souvenir or object you keep as a reminder. And “Mori” is death.

[Please note it is “memento mori” — not “momento mori”.]

Memento Mori Origin & History

1. Origin Story of Memento Mori

Memento mori was held in high regard in ancient Rome. This is that origin story.

Rome in those days had the tradition of holding a ‘triumphus.’ It was a gala parade to honor a triumphant general who had just returned from the battlefield.

The victorious general would enter Rome riding a four-horse chariot.

The people he captured were held in chains, and the souvenirs he seized were laid on trolleys, both paraded ahead of his horses.

His troops would march beside and behind his chariot.

The procession would march through the streets to reach the temple of Jupiter, where the general was to offer a sacrifice.

People would throng in large numbers on the sides of the streets, shouting the deeds of their hero and rejoicing at the occasion.

A triumphal procession tended to fit a formula. First to come were the captive leaders, usually walking in chains. They were followed by their captured weapons and armor, along with the spoils of war and any exotic objects which might impress the citizens of Rome.

The ultimate bit of propaganda, a procession of painted posters and statues depicting the notable events of the campaign, came next, followed by Rome’s senators and magistrates, all on foot as a sign of humility before the great hero of the hour. The conquering general came towards the end in a four-horse chariot, dripping with gold leaf and animal furs, followed by his loyal soldiers wearing laurel leaves and togas and shouting in unison “io triumphe” — behold the triumph!

— John Welford, retired librarian, Leicestershire

The lofty triumphus, the most cherished ambition of every Roman general, was extremely hard to obtain.

The Roman senate did not grant every battle-winner this honor. Of the many conditions, one was that the general must have slain at least 5,000 of the enemy in a single battle.

The triumph parade was such a magnificent ceremony that it could make any general feel like a god.

Here comes the twist in that tale. In the chariot, as legend has it, a slave stood close behind the euphoric general.

This slave’s sole duty was to whisper into the ears of the commander every once in a while:

“Remember, you have to die.”

That repeated reminder of his mortality forced the general to take in the entire scene wisely and reasonably.

It told him to stay humble on this grand occasion, and not think he was the new god of Greece.

It warned him that when he dies, his heroic tales, fame, and luxury will be soon forgotten.

This custom was the origin story of the memento mori tradition.

But how could a piece of Stoic advice to keep death in mind be rational? And how could a reminder that you are going to die free you from your fears?

See these Memento Mori Bracelets: Wearable Symbols of Life’s Fragility.

2. Memento Mori In Stoicism

The concept of memento mori, or death remembrance, is a central tenet of Stoic philosophy.

Stoics believe that death is a part of life. So, instead of fearing it, we should use death awareness as a motivation to live our lives to the fullest.

However, memento mori was not a tradition of the Early Stoa (Zeno to Antipater), or the Middle Stoa (Panaetius and Posidonius). It was the philosophers of Late Stoa—the Roman Stoics—who took up the idea of memento mori.

These Roman Stoics extensively used memento mori to urge people to live virtuously. They taught that people had only a little time to do good since death could come at any moment.

In fact, people lived very short lives back then. The average life expectancy in the Roman Empire was just over 20 years. And 50% of infants born in Rome would die before they reached ten years old (Stoicism and death acceptance, Menzies & Whittle, 2022).

Memento mori told them to stop being arrogant or narcissistic, jealous or envious, or spiteful or mean.

Dead people cannot take their worldly possessions and recognition with them. When they die, everything stays behind, even if their graves are filled with riches.

They saw each day as a gift and stopped wasting time on trivial matters. It is a good reminder for us today, as we waste time scrolling social media for hours.

Ryan Holiday, who single-handedly brought Stoicism into modern social consciousness, is fond of saying,

“Live your life as if you’re not sure whether your time on this earth is ending or not. Get your s**t together. Handle what’s important. Take care of others. Enjoy yourself. Be at peace.”

But death is such a fearful thing, you may exclaim in horror.

The Stoics tell us that death, a natural part of life, is nothing to be afraid of.

Epictetus said, “If you’re fond of a jug, say, “This is a jug that I’m fond of,” and then, if it gets broken, you won’t be upset.” Think of that jug as your life, and you lose the fear of your own death.

The Stoic sages Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius extensively meditated on their own death. They gave us this mind-altering understanding of death:

Death is not waiting for us at the end of our lives, but it is already upon us. Death has already claimed each day that we have lived until now.

It opened my eyes to a profound realization when I first learned about it.

Seneca On The Shortness of Life

Seneca, the Roman philosopher, statesman, and dramatist, wrote about the importance of memento mori in his essay “On the Shortness of Life.”

He said, “It is a wise man who, when he looks upon the life of man, remembers that it is short and fleeting.”

Seneca believed that the awareness of death can help us to focus on what is truly important in life, and to live each day as if it were our last.

Seneca advised,

“Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life’s books each day. … The one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time.”

Marcus Aurelius On Being Like A Dying Person

The philosopher king of the Roman Empire (read his most famous quotes here) frequently reminded himself of his death:

- Once he was telling himself: “Do not act as if you were going to live ten thousand years. Death hangs over you. While you live, while it is in your power, be good.”

- Then he reminded himself thus: “Think of yourself as dead. You have lived your life. Now, take what’s left, and live it properly.”

- And once again, he warned himself: “Let each thing you would do, say, or intend, be like that of a dying person.”

The phrase “Yesterday, you said tomorrow” is thought to have originated in ancient Rome, where it was used as a reminder of the inevitability of death.

The idea was that if you put off something important until tomorrow, there is no guarantee that you will actually get to it tomorrow. You could die before then, and then you would have missed your chance.

It was used by the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, who said,

“Yesterday, you said tomorrow. Make today the day.”

Epictetus On Freedom From Fear of Death

Epictetus, the former slave who became a Stoic Philosopher, also stressed the importance of memento mori and often said, “Remember that you are mortal, and that you will die.”

Epictetus believed that awareness of death could help us to live a more virtuous life, by freeing us from the fear of death and allowing us to focus on the present moment.

He often reminded his students this way:

“If you kiss your child or your wife, say to yourself that it is a human being that you’re kissing; and then, if one of them should die, you won’t be upset.”

— Epictetus, Enchiridion, 3

That advice from Epictetus seems inhumanely cruel. William Irvine, the author of A Guide to The Good Life, tries to explain its import.

Irvine says that parents who remember the transience of life will never take their children for granted. They would instead pause each day to shower them with love and appreciation.

Epictetus’ more palatable advice on death was:

“Keep death and exile before your eyes each day, along with everything that seems terrible— by doing so, you’ll never have a base thought nor will you have excessive desire.”

3. Story of Diogenes And Memento Mori

Diogenes the Cynic was a rebel philosopher of ancient times who lived in a wooden cask and barely wore clothes. He stressed extreme self-sufficiency and the absolute rejection of luxury.

In his honor, behavioral scientists named Diogenes syndrome, a disorder of older men and women. Its main symptoms are excessive hoarding, dirty houses, and poor personal hygiene.

Once, Diogenes of Sinope was asked how he wished to be buried.

He replied that he wanted them to throw his body outside the city walls, unburied. They expressed concern that wild beasts would feast on him and asked if it would upset him.

Diogenes replied, “Not at all, as long as you give me a stick to chase the creatures away!”

They laughed and pointed out that since he would be dead and hence have no awareness, he couldn’t fend off the wolves with his stick.

To this, Diogenes replied,

“If I lack awareness, then why should I care what happens to me when I’m dead?”

He was unconcerned about what happened to his body after death. To him, how he practiced his philosophy of Cynicism while he lived was more important.

With memento mori, we also stop worrying about what would happen to the people we love, and who would take care of them, along with our pets and plants. Instead, we go ahead and love them more in our lifetime.

Memento mori reminds us that the great equalizer, death, awaits us.

4. Memento Mori And Egyptians

The Romans and the Egyptians were destined to share profound bonds in history.

- Julius Caesar fell in love with Cleopatra and helped her ascend to the throne of Egypt as its sole ruler.

- After Julius Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra began a romance with Marcus Antonius or Mark Antony, the Roman general.

- Then, when Mark Antony faced a violent defeat at the Battle of Actium, Cleopatra chose suicide by snake bite rather than being captured.

- The man coming after Cleopatra was Octavian or Augustus, the first emperor of Rome.

- Augustus took the whole of Egypt for himself, and the Nile-irrigated Egypt became the breadbasket of Rome.

The Egyptians had always celebrated the lore of memento mori in a way that was much grander than that of the Romans.

For them, death was merely a passage into an afterlife. They built magnificent pyramids as timeless shrines to the pharaohs resting in their graves.

The pyramids display the unique way the Egyptians remembered death. They show how the Egyptians had devised ingenious methods to mummify the corpses.

They fabricated exquisite face masks for their dead and were experts at designing intricate and luxuriant death chambers. All to show their many ways to honor life, even in death.

5. Memento Mori And Church

This idea of “keeping death in mind” spread with the growing influence of the Church.

In the 2nd century, the Christian writer Tertullian’s version of the triumphal parade described the slave as whispering,

“Respice post te. Hominem te memento.”

Translation: “Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you’re [only] a man.”

Ars Moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) was the first Medieval text on dying and preparing for death in European devotional literature. It was published around 1415 CE, probably at the request of the Council of Constance, Germany. It offered practical advice on the rites and procedures of a good death and how to “die well.”

Ars Moriendi was a much-needed response by the Roman Catholic Church to the horrific effects of the Black Death.

The first chapter of Ars Moriendi explains the good side of death and assures the dying person it is nothing to be afraid of.

The Book of Ecclesiasticus (Wisdom of Sirach), 7:40, reads as:

“In all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.”

Memento Mori In Popular Culture

The concept of memento mori has been important in Western culture throughout the centuries. Used in art, literature, and philosophy, it continues to be a reminder to us that we should live our lives to the fullest, knowing that death is inevitable.

1. Music & Dance

Memento mori was a genre of requiem and funeral music, and it had a rich traditional history in early European music. Jewelry like rings and pendants, pens, belts, skulls, and coffin motifs inspired by memento mori became popular towards the end of the 16th century.

Another notable genre of memento mori is Danse Macabre (Dance of Death). It is a species of dramatic play that spotlights the universality and inevitability of death.

The tradition traces back to the middle of the 14th century. The early plays featured a skeletal figure wearing a hooded robe and carrying a scythe: The Grim Reaper.

The Grim Reaper would ambush a powerful person, usually a king or a pope, and tell them their time is over. As he took him to his grave, he called on people from all walks of life to dance all the way to the cemetery.

The purpose was to remind them of the fragility of life and the futility of earthly glories. It was a memento mori, that death was coming for them, regardless of where they lived.

The Danse Macabre also found expression in fine art, and many murals, frescoes, and paintings celebrated it.

The “Triumph of Death” at Pisa’s cemetery, painted between 1360 and 1380, is one of the most famous paintings on the theme. The Cemetière des Innocents in Paris may have the oldest image of the Dance of Death (1425).

Hans Holbein the Younger was one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century. He crafted a series of the “most marvelous woodcuts ever made” on Dance of Death. The first book edition, containing forty-one of Holbein’s woodcuts, came out in 1538.

2. Books & Literature

Among the best-known literary meditations on death in English are Sir Thomas Browne’s The Urn of Burial and Jeremy Taylor’s The Holy Dying.

The Roman poet Horace used the Latin phrase “carpe diem” to exhort people to “seize the day.” It was to tell the people that they should enjoy life while they can since no one is promised a tomorrow.

In the eleventh poem of his Odes, published in 23 BCE, he wrote:

“carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero”

It translates as “pluck the day, trusting as little as possible in the next one.”

Epicurus, who lived around 300 years before Horace, philosophized on the idea of carpe diem.

The Epicureans believed living for today while enjoying the pleasures of life can help them attain a state of tranquility or ataraxia.

Epicurus believed pleasure is the greatest good, and one should live a life of pleasure, free from all fear. The Epicurean way to a happy life is something we can achieve today, once we are ready. Epicureanism later became the inspiration for Horace.

The man who has learned to die has unlearned how to be a slave; he is above all power, or at least beyond its reach. What do prison and guards and locked doors mean to him? He has a free way out. There is only one chain that keeps us bound, the love of life, and even if this should not be rejected, it should be reduced so that if circumstances require nothing will hold us back or prevent us from being ready instantly for whatever action is needed.

— Epicurus

Shakespeare wrote of death in many of his plays. Hamlet—Prince of Denmark explores death in its many aspects. The play begins with the appearance of the ghost and ends with several violent deaths.

In between, Hamlet contemplates suicide and develops an obsession with death.

In an iconic moment, Hamlet holds up the court jester Yorick’s skull and ponders its transition from life to death. Hamlet grieves on what becomes of even the most alive and vibrant of people after death—reduced to a hollow skull.

Hamlet finally accepts death, without fear or longing, and points out that “the readiness is all.”

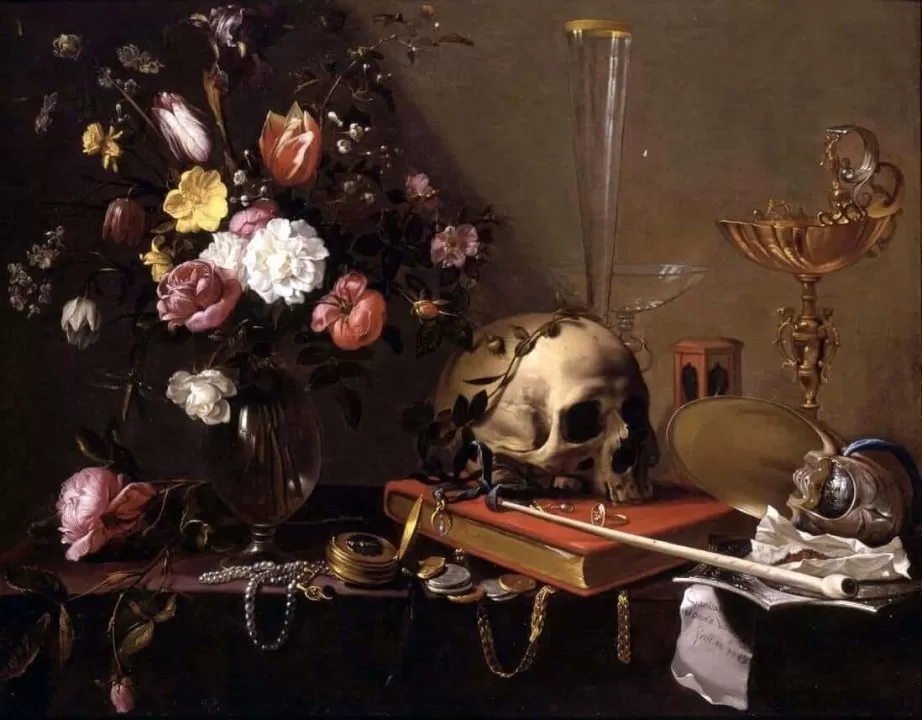

3. Art: Vanity, Vainglory, And Death

Perhaps the most notable art genre associated with memento mori is vanitas, which started emerging in the later years of the 15th century.

They showed both vanity (deep interest in appearance and achievements) and vainglory (excessive boastfulness and vulgar display), and their futility at death.

The painting above is inscribed with these Latin words: “ipsa adeo morti vel formosissima cedvnt.” Translated, it means “Even the most beautiful one gives in to death.”

The vanitas art form focused on still life and contained various symbols reminding the viewer of the worthlessness of worldly goods and vanities.

Mostly, they carry traditional memento mori symbols such as skulls, extinguished candles, withered flowers, books, hourglasses, sundials, and musical instruments.

Memento mori art: Some famous paintings centering on memento mori are:

- “Skull” by Albrecht Dürer, 1521

- “The Scream” by Edvard Munch, 1891

- “The Nightmare” by Henry Fuseli, 1781

- “Pyramid of Skulls” by Paul Cézanne, 1901

- “Young Man with a Skull” by Frans Hals, c. 1626

- “Bull Skull, Fruit, Pitcher” by Pablo Picasso, 1939

- “Skull with Burning Cigarette” by Vincent van Gogh, 1885

- “Still-Life with a Skull” by Philippe de Champaigne, c. 1671

- “Saturn Devouring His Son” by Francisco Goya, c. 1819-1823

- “Girl with Death Mask (She Plays Alone)” by Frida Kahlo, 1938

- “Judith Slaying Holofernes” by Artemisia Gentileschi 1614-1620

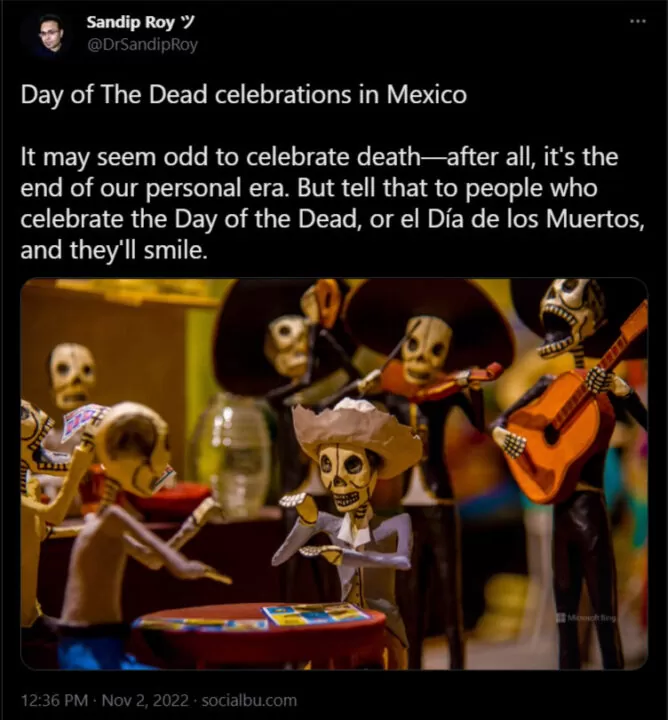

4. Day of The Dead

The Day of The Dead (Día de los Muertos) is celebrated all throughout Mexico, and other Latin American countries like Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Guatemala.

Every November 1st and 2nd, they build altars to honor their deceased family members, decorated with marigolds, candles, incense, food items, and toys.

It originated with the Mayans (250 to 900 CE) and the Aztecs (1345 to 1521 CE). They believed it was the way a person died that dictated where the soul would go in the afterlife.

The Mayans held that those who died by suicide, sacrifice, in battle, and during childbirth, had their souls go straight to heaven.

Similarly, the Aztecs held the souls of soldiers slain in battle, and the women who died giving birth traveled with the sun into the heavens. While the souls of those Aztecs, who died a normal death, had to pass through nine levels of the underworld.

Based on these beliefs, those ancient civilizations developed a rich ritual around the cult of ancestors and death.

In later days, they transformed into the current Mexican celebrations of the Day of the Dead. In 2008, UNESCO added it to its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Since 1994, the citizens of Aguascalientes, a city in central Mexico, have celebrated the Festival de Calaveras, or the “Festival of the Skulls.” It draws from the Day of the Dead tradition.

Why is memento mori important?

Memento mori is important because it helps us face death fearlessly. Remembering death makes us want to live for goodness, not for profit or glory.

Once we are ready for death, we no longer bother about who would claim our lands and goods, or what might happen to our legacy.

- It can help us to live in the present moment. When we are constantly aware of our own mortality, we are less likely to dwell on the past or worry about the future. We are more likely to focus on the present moment and appreciate the good things that we have in our lives.

- It can help us to let go of attachments. When we realize that death is inevitable, we are less likely to become attached to material possessions or worldly success. We are more likely to focus on what is truly important in life, such as our relationships with loved ones and our own personal development.

- It can help us to live a more virtuous life. When we are aware of our own mortality, we are more likely to act in a way that is consistent with our values. We are less likely to engage in harmful or destructive behaviors, and we are more likely to help others and make a positive contribution to the world.

Everyone dies. So, why remember it?

When we remember that we may die, we cherish our loved ones. We remember to talk to them, hold them close, and give them our presence. We leave them with good memories of us.

How can we benefit from practicing memento mori?

Memento mori is a powerful reminder to live a meaningful life. Here are some benefits of practicing memento mori: It helps us to:

- Appreciate our relationships

- Be mindful in everything we do

- Not delay carrying out our duties

- Disconnect from the future results

- Accept death as non-intimidating

- Be grateful for the things we have

- Let go of the grudges and regrets

- Work harder towards our life goals

- Avoid hubris, anger, egoism, vanity

- Focus on the processes and actions

- Try learning/experiencing new things

- See the transience of wealth and fame

- Accomplish more, live better, love deeper

How to practice the memento mori meditation?

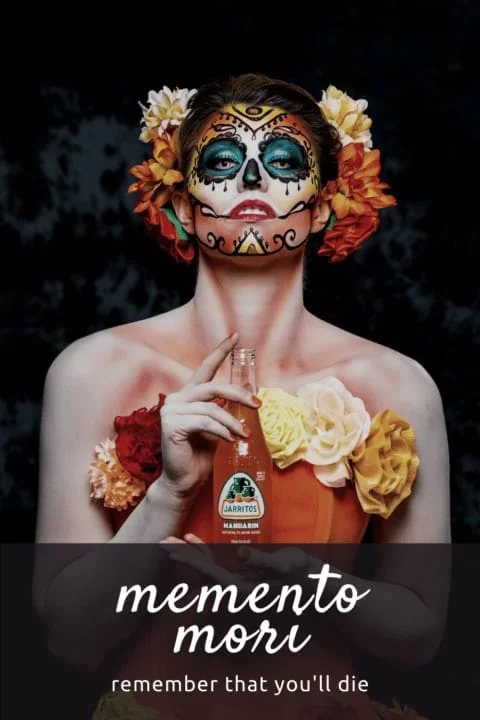

Those who practice memento mori often carry a personal symbol to embrace the impermanence of life.

A memento mori ring, memento mori jewelry, memento mori coin, or memento mori watch that urges them to finish their moral duties before “death smiles at us”.

It reminds them how useless are earthly riches, status symbols, and titles. And how short our time on Earth is.

Some people like to have a memento mori tattoo on them.

Here’s how to practice the memento mori meditation:

- Find a quiet place where you won’t be disturbed.

- Sit in a comfortable position and close your eyes.

- Take a few deep breaths and relax your body.

- Bring to mind the image of a skull. This can be a real skull, a picture of a skull, or even just a mental image of a skull.

- As you look at the skull, remind yourself that you will one day die.

- Think about what death means to you. What are your fears about death? What are your hopes for death?

- Spend some time sitting with these thoughts and feelings.

- When you’re ready, open your eyes and return to your normal awareness.

The memento mori meditation is a powerful tool, so be gentle, patient, and kind to yourself as you do it. If you find yourself getting scared or anxious, stop.

Try another method, like watching this Ryan Holiday TEDx talk:

Read my pick of the 10 Best Books On Stoicism.

FAQs

How does the concept of ‘memento mori’ influence Stoic philosophy?

The Stoics used memento mori to remember life’s shortness and to build priorities and meaning. They treated each day as a gift and reminded themselves constantly not to waste any time on trivial and vain things. It reminded the Stoic that the things of the world, such as the body, fashion, career, reputation, and wealth, should not be the primary focus because these things can be swept away by death in a moment. Today, thousands of modern Stoics carry memento mori coins or wear memento rings to keep the thought of death with them at all times. It inspires them to make the most of each day and to live a life of purpose and meaning.

What is the historical significance of ‘memento mori’ in ancient Rome?

“Memento mori” in ancient Rome served as a reminder to generals and leaders of their mortality. It aimed to keep them humble and grounded despite their successes. As a general’s victory parade rode through the streets, a slave who stood behind him whispered in his ear, “Memento mori.” This was a reminder that even the most powerful and victorious general was not immune to death.

How does memento mori connect with Halloween?

Halloween, also known as All Saints Eve, began to be observed around 1556. It heralds the arrival of winter and is celebrated as a day when the graves may open and “the dead awake and speak to many.” Today, it is tightly woven into popular culture all across the world. The true message behind Halloween is an ancient one: Memento mori.

In what ways can ‘memento mori’ impact our daily lives and decision-making?

Here are some ways memento mori can improve our daily lives and decision-making:

It can help us to appreciate the present moment. When we are constantly aware of our own mortality, we are less likely to dwell on the past or worry about the future. We are more likely to focus on the present moment and appreciate the good things that we already have in our lives.

It can help us to let go of attachments. When we realize death is inevitable, we are less likely to become attached to material possessions or worldly success. We are more likely to focus on what is truly important in life, such as our relationships with loved ones and our own personal development.

It can help us to live a more virtuous life. When we are aware of our own mortality, we are more likely to act in a way that is consistent with our values. We are less likely to engage in harmful or destructive behaviors, and we are more likely to help others and make a positive contribution to the world.

It can help us to make better decisions. When we are aware of our own mortality, we are more likely to make decisions that are aligned with our values and that will have a positive impact on our lives. We are less likely to make impulsive or reckless decisions that could have negative consequences.

Final Words

[Download the PDF – Memento Mori, Meaning, Origin, Culture, Importance]

Finally, here’s a brutal reality about memento mori.

People in Roman Stoic times lived in an extremely violent world. Wars, diseases, famines, and tyrants kept reminding them that the Grim Reaper lurked near.

Memento mori was a forced, cruel burden on their brief lives, as they were reminded every day that they may die today. They didn’t have to buy human skull jewelry.

Over the centuries, as health care and human lives improved, lifespans increased. That brutal version of the memento mori left our social consciousness. Today, we expect to live much longer. Yet, death remains just as unpredictable.

Death is something that I cannot escape, So whenever my time comes, I accept my fate. I’ll carry to the afterlife my heart and soul, But I accept the inevitable, And what I cannot control. So I will live in the moment, one day at a time, And each day I’ll show gratitude, For this life I call mine. I am not scared, since my life is a story, So I’ll live by these words, Memento Mori. — Matt Lillywhite, Sep 2020

Death has been following us our entire lives, and it can come in without knocking. So, carpe diem as you memento mori.

• • •

• • •

Author Bio: Researched and reviewed by Dr. Sandip Roy. His expertise is in mental well-being, positive psychology, narcissism, and Stoic philosophy.

√ If you liked it, please spread the word.