— Researched and written by Dr. Sandip Roy.

Imagine standing on a stage with a microphone stand, about to deliver a speech to a large crowd, heart pounding, hands trembling.

That’s called glossophobia, and it is the commonest human fear.

Fear can be explained as a chain reaction. It starts with a stressful event, activates our brain, and releases certain chemicals that make our body react.

Key Takeaways

- Humans couldn’t have survived or evolved without fear.

- Each bodily effect of the fear response system has a purpose.

- Understanding and confronting fears are key to overcoming them.

The Psychology of Fear

Fear formed the basis of human evolution

Fear is a primal emotion.

Our prehistoric forefathers ran first and checked later if the rustling sound was caused by wind in the leaves or a predator.

In the ancestral wilderness, fear helped instant recognition of and reaction to threats.

Those who ran, survived and reproduced. And passed this evolutionary fear response system to us.

A peril rarely makes the difference between life and death today.

Therefore, we often hate what fear makes our bodies and minds do. We don’t want ourselves to act as if we were still living in early jungles.

Fear can be helpful sometimes, like heightened awareness and safety instincts, but most fear responses are uncomfortable in modern life.

Decoding the brain’s fear response system

The amygdala is the brain’s epicenter for processing fear.

Threats, real or perceived, activate the amygdala. It “remembers” how an ancestor reacted to a danger and coordinates the other parts of the brain to send out signals.

The activated brain sets off the fight-or-flight response, a critical alarm system for survival that primes the body for action, much like how our ancestors reacted.

This triggers a cascade of bodily reactions — increased heart rate, rapid breathing, dilated pupils, and sweating.

Surprising ways our bodies handle fear

Fear triggers several physiological responses, each with its own useful purpose:

- Rapid Breathing (Hyperventilation): This increases oxygen intake and makes more oxygen available for the muscles. When we are well-oxygenated, we can either tackle the threat or run away from it.

- Increased Heart Rate: More beats per minute allow the heart to pump blood faster, which ensures that the vital organs and muscles receive more oxygen and nutrients. This readies the body for quick and vigorous action to confront the danger (fight) or to flee from it (flight).

- Sweating: Sweating helps to regulate the body’s temperature during the stress response. When your body prepares for action, it generates heat. Sweating cools the body down, preventing overheating. Moreover, sweating can also make the skin more slippery, potentially helping escape a predator’s grasp in a survival scenario.

- Pupil Dilation: Fear can cause the pupils to dilate (widen), allowing more light into the eyes. This improves vision, especially in low-light conditions, enhancing the ability to detect and respond to threats quickly.

- Hair Standing on End (Piloerection): Often experienced as ‘goosebumps,’ it has historically helped animals appear bigger and more intimidating to predators. In humans, it’s more of a vestigial reflex, but it can enhance sensory perception by making the skin more sensitive.

- Slowing Down of Non-Essential Bodily Functions: Digestion and immune responses may slow down or temporarily halt, allowing the body to conserve energy and redirect it towards a swift response to the immediate threat.

These mobilize us to either face our fears head-on or to quickly flee. Strangely, some people don’t flee or fight; they freeze.

Different people respond to fear differently.

People have unique ways of processing fear, and the same fear can be different for different people.

Our response to fear is vastly influenced by our temperament, traits, and life experiences.

- Some people are highly sensitive to fear, making them extra cautious and over-reactive to perceived threats. It is their natural temperament.

- Personality traits, such as neuroticism, can make some individuals more prone to anxiety and fearfulness.

- Of course, past traumatic experiences can shape and even heighten one’s fear response.

So, while fear can be complex, we can also handle it in more complex ways based on our personal history and character traits.

The Downsides of Fear

Fear can be limiting when it is excessive or when we cannot manage it well.

Excessive or irrational fear can lead to anxiety disorders, intense phobias, and a constant feeling of being in distress.

Such intense fear responses can limit your range of activities, make you avoid certain situations (avoidance behaviors), and obstruct personal and professional growth.

Irrational fears (phobias) can prevent you from trying unfamiliar and challenging activities, making life dull and tiresome.

A fear of failing can also stop you from going after your goals, lead to missed opportunities, obstruct your coping skills and growth, and make you have unnecessary regrets later on.

When faced with public speaking, our fight-or-flight response can be activated. This fear response is because of social and evolutionary factors:

- Socially, there is a fear of negative judgment or rejection from the audience, which can trigger feelings of embarrassment or shame. Moreover, public speaking can be seen as a high-stakes situation, increasing the pressure to perform well.

- Evolutionarily, humans are wired to be alert to the scrutiny of others, as historically, survival often depended on social standing within a group.

Fear’s Positive Role

Fear is a first instinct. It is our natural “guardian angel” that points out the dangers in our environment. This helps us take precautions.

However, beyond mere survival, fear can stimulate positive actions like:

- Practicing extensively before a public presentation

- Prompting us to drive safely in hazardous conditions

- Encouraging double-checking work for accuracy to avoid mistakes

- Leading to disciplined training for competitive events, like a test or a sports match

- Motivating meticulous planning or rehearsal before important meetings or interviews

- Taking additional education or training to improve job performance or career prospects

- Driving precautionary health and safety measures during travel or in high-risk environments

Examples of Fear’s Dual Nature

- Public Speaking: Fear of speaking in front of a crowd can drive you to prepare well, increasing your chances of delivering engaging and convincing talks. However, if this fear becomes a phobia, you could start avoiding public speaking opportunities, hindering your growth.

- Parenting: A parent’s fear for their child’s safety is vital, but some parents may adopt excessive protective measures and helicopter parenting. Such overprotectiveness can stifle the child’s ability to explore and become independent.

Learning and Conditioning in Fear Formation

Our fears are significantly shaped by learning and conditioning experiences.

Classical conditioning, a concept made famous by Pavlov’s dog experiment, illustrates how fear can be conditioned through association.

For instance, if a person experiences a traumatic event with a specific object or situation, they may develop a fear response to similar objects or situations in the future.

Observational learning also plays a role.

Witnessing others reacting fearfully to certain stimuli can instill similar fears in an observer, even without a direct negative experience. This form of learning highlights how fears can be transmitted socially and culturally.

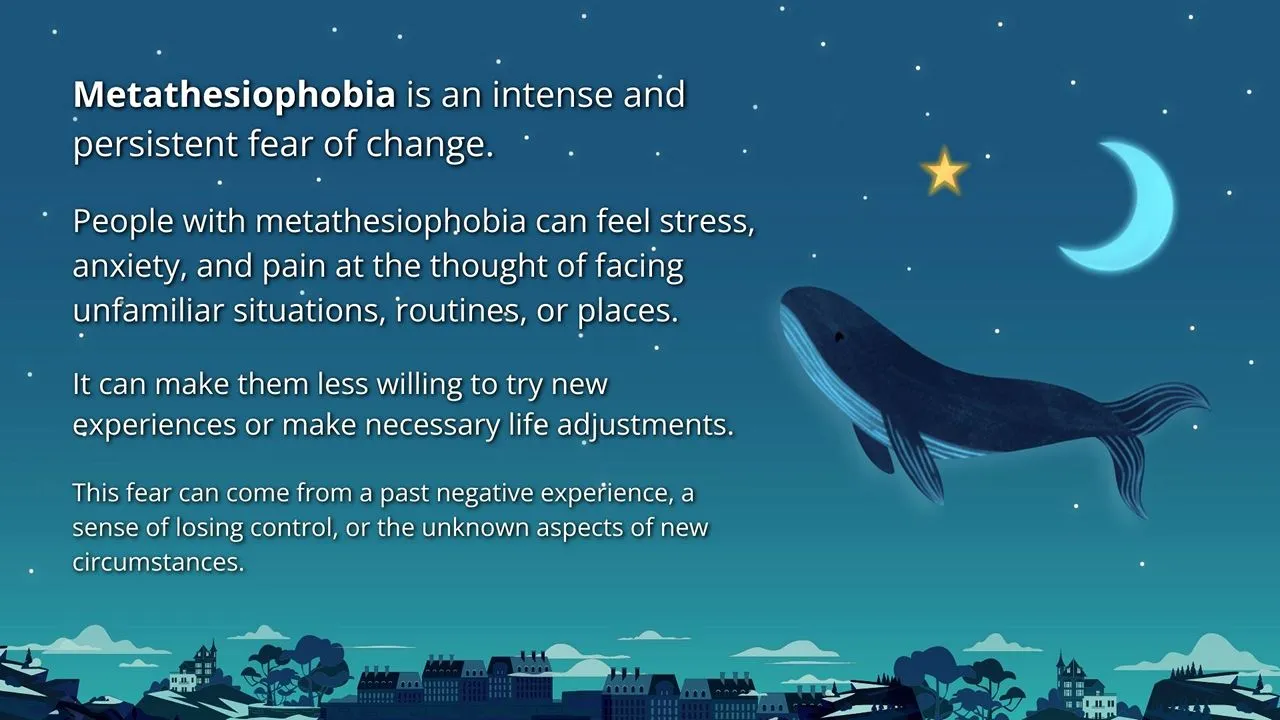

Innate Fears Versus Learned Fears

Innate fears are evolutionary fears, like acrophobia (fear of heights) or arachnophobia (fear of spiders), that are passed down through generations.

Learned fears, like fear of public speaking or flying, develop through personal or societal experiences. These are not universal, and are often complex.

| Aspect | Innate Fears | Learned Fears |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Evolutionary and instinctual, serving as survival mechanisms | Developed through personal experiences or societal influences |

| Examples | Fear of heights, spiders | Fear of public speaking, flying |

| Onset | Often immediate and instinctual | Gradually acquired over time |

| Universality | More universal, commonly shared across humans | Varies widely among individuals |

| Influences | Hardwired in human genetics | Influenced by cultural, environmental, and personal factors |

| Purpose | Primarily for immediate survival and avoidance of harm | Often related to complex social or specific situational anxieties |

| Changeability | Generally consistent throughout life | Can change or evolve based on new experiences or understanding |

Different Categories of Phobias

Phobias represent extreme or irrational fears of specific objects, situations, or environments.

These are 10 different categories of phobia:

- Agoraphobia: The fear of wide open spaces, crowds, or uncontrolled social conditions from where escape might be difficult or help wouldn’t be available. It can include fear of open spaces, public transportation, crowded places, or simply being outside alone.

- Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder): Fear of social situations due to worry about embarrassment or being judged negatively by others. It can lead to avoidance of social interactions, impacting one’s personal and professional life.

- Mysophobia: Fear of germs or dirt, often related to obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Trypophobia: Fear of clusters of small holes or bumps.

- Glossophobia: Fear of speaking in public.

- Thanatophobia: Fear of death or dying.

- Nyctophobia: Fear of darkness or night.

- Acrophobia: Fear of heights.

- Autophobia: Fear of being alone or isolated.

- Specific Phobias: Intense fear of specific objects or situations, such as Animals—Spiders (arachnophobia) and dogs (cynophobia); Natural Environments—Fear of lightning and thunder (astraphobia, brontophobia), sea (thalassophobia), sun (heliophobia), hydrophobia (water); Situations— Like enclosed spaces (claustrophobia) and flying (aerophobia); Other Phobias—Like fear of loud sounds or costumed characters.

Managing Fear Using Cognitive Science

In real danger, fear can be critical for self-preservation. However, many humans suffer from unrealistic and chronic fears, like phobias and obsessions.

Here are some ways to handle those fears:

Therapeutic Approaches for Handling Fear

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): Aims to help individuals recognize and modify distorted perceptions related to fear and anxiety-provoking situations.

- Exposure therapy: As a part of CBT, this method involves gradual, controlled exposure to the source of fear, aiding in confronting and overcoming fears.

- Mindfulness techniques: Focuses on being present and observing thoughts and feelings non-judgmentally, helping in reducing anxiety and enhancing relaxation.

- Social cognitive theory application: Used by therapists to treat fear and other psychological conditions.

- Psychological treatments: These treatments address the root cause of fear using a psychodynamic approach or tackle the fear directly through behavioral therapy.

- Cognitive restructuring: Cognitive restructuring can help individuals manage their fears.

Practical Tips for Managing Fear in Everyday Life

- Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation can help reduce physical symptoms of fear.

- Gradual exposure to fearful situations can build confidence and reduce avoidance behaviors.

- Confiding in friends and family can provide encouragement and guidance.

- Positive self-talk can challenge negative thoughts associated with fear.

Further Reading

- The Gift of Fear by Gavin de Becker: Examines intuition and how fear can serve as a protective guide.

- Wherever You Go, There You Are by Jon Kabat-Zinn: Explores mindfulness and its role in managing anxiety and fear.

- Research on Classical Conditioning by Ivan Pavlov: Provides foundational knowledge on how fears can be learned.

- Studies on Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety.

- Trypophobia — The Mysterious Holes-In-Hand Phobia.

FAQs

Is our fear response the same as the fight-or-flight response?

Yes, the fear response is closely related to the fight-or-flight-or-freeze response. This response is an automatic physiological reaction to a perceived harmful event, attack, or threat to survival.

Originally termed the “fight-or-flight” response by Walter Cannon, it describes how an animal or human mobilizes for defensive action — either to fight the threat or flee from it. The term has since been expanded to include “freeze,” recognizing that sometimes individuals become immobilized or unresponsive in the face of fear or trauma.

Final Words

Our lives are often blocked by fear. Yet, we can find our greatest strength within this challenge. We can make fear a guide to a fulfilling and balanced life rather than a barrier.

Start by asking: How can I transform my fears into stepping stones for growth and resilience?

√ Also Read: How To Make A Narcissist Fear You – 35 Ways To Outsmart Them

√ Please spread the word if you found this helpful.

• Our Story!