Today's Tuesday • 25 mins read

“There is no angry Stoic.”

— Donald Robertson, author & philosopher

Robertson means that Stoicism, properly understood and practiced, doesn’t leave room for sustained anger. So, even when Stoics may get feelings of anger, they do not carry their anger or act out of it.

Anger is a judgment-driven, reactive passion that conflicts with Stoic aims of rational assent, emotional resilience, and right living.

They know that anger is a natural emotion, so we may not always stop it from appearing. But we can respond to it by not blocking out our anger, but by limiting its virulent spread.

Most of us do not know how to control our anger. As a result, we are “very like a falling rock which breaks itself to pieces upon the very thing which it crushes,” as Seneca put it.

“While trying to ruin its target, anger ruins the one who holds it. That is the curse of anger.” — Seneca

The Stoics developed some highly helpful principles for managing anger. Seneca even wrote an essay that explains human anger and offers guidance on how to prevent and control it from a Stoic perspective.

How Stoics See Anger: Stoic Philosophy of Anger

- Anger is an unhelpful, excessive passion. Stoics, from Zeno through Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, classify anger as a diseased, excessive impulse. As an irrational overvaluation of some perceived wrong that disrupts our peace of mind and moral reason.

- Anger rests on false or exaggerated judgments. Stoic ethics aim for correct judgments. For Stoics, impressions (what we perceive) must be examined; assent is only given to what’s in our control and properly valued. Self-righteous anger is anger that someone’s action is a catastrophic insult to us, that justice requires our violent retribution, or that our dignity is destroyed. A rational Stoic will withhold assent to those impressions.

- Practical self-command replaces rage. Instead of anger’s heat, Stoicism prescribes measured responses: quiet indignation (prohairesis directed at duty), corrective action, or calm withdrawal. Anger’s aim, to punish, dominate, or vent, contradicts the Stoic commitment to wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation.

- Short-term vs. momentary reactions. Robertson’s phrasing can be read strictly (no Stoic ever feels any twinge of irritation) or more charitably: a true Stoic does not live in or act from anger. Stoics acknowledge natural impulses and can experience fleeting upset, but they discipline their impressions so anger does not govern action or character.

- Social and therapeutic rationale. Anger harms relationships and clouds judgment; eliminating it preserves community, effective action, and inner tranquility, which are central Stoic goods.

- Anger can also block kindness and compassion. Stoicism emphasizes cosmopolitan regard and oikeiōsis (recognizing our shared human nature). Anger narrows perspective, fosters contempt or withdrawal, and prevents the benevolent responses like forgiveness, patience, and constructive correction. That is another reason Stoics see anger as a vice incompatible with Stoic character.

“Mankind is born for mutual assistance, anger for mutual ruin.” — Seneca

By learning to control our anger, we can lead happier lives and contribute to a more peaceful world.

The ancient Stoics were not just philosophers but also physicians, teachers, and politicians who wanted to apply their philosophy in everyday life. They encountered anger in their daily lives and saw its ravages. They noted that actions taken in anger were almost always regrettable.

So, they devised a way to use Stoicism as a tool to manage and cope with anger.

And found it helped people reduce their anger and other related negative emotions like frustration, regret, and grief.

Our power to remain calm lies in controlling our angry responses.

The Stoics started with a root principle of Stoicism, that the only things we have control over are our thoughts and actions.

They felt that if we stopped trying to control the things that cause us anger, most of which are things we can’t change, we could achieve happiness in life.

Why do we feel anger?

We mostly get angry when people fail to meet our expectations, make us feel small, or betray our trust.

Norman Cotterell, Ph.D., feels, “Anger is built on expectations. We expect people to treat us fairly, and they don’t. Each time there is a gap between expectation and reality, anger is more than willing to fill in that gap.”

And Rosenberg says,

“Every criticism, judgment, diagnosis, and expression of anger is the tragic expression of an unmet need.”

— Marshall B. Rosenberg, American psychologist, Founder of The Center for Nonviolent Communication.

When we think others have failed to do as we expected, we become angered.

“We are more often frightened than hurt, and we suffer more from imagination than from reality.”

— Seneca

Most people behave scandalously when they are angry because they do not know how to manage this primal emotion.

“Anybody can become angry – that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way – that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.”

— Aristotle, pre-Stoic Greek philosopher and polymath

Some people have always believed that anger, when done in moderation, is helpful in certain situations, like:

- A burst of anger can spark greater creativity.

- It can establish a leader’s authority to get things done right and fast.

- It can be helpful or necessary in the face of perceived injustice (though the hardcore Stoics dispute it).

For most purposes, however, anger is destructive with far-reaching consequences. Unmanaged anger and hostility can be harmful to your heart’s health, shows research.

Studies suggest chronic anger leads to vascular damage over time. Short bursts of anger may temporarily hamper the ability of blood vessels to properly dilate, which may prevent arteries from hardening (Shimbo & Cohen, 2024)

“If you’re a person who gets angry all the time, you’re having chronic injuries to your blood vessels. It’s these chronic injuries over time that may eventually cause irreversible effects on vascular health and eventually increase your coronary heart disease risk.” — Dr. Daichi Shimbo

Two Principles of Anger Control In Stoicism

“How much more harmful are the consequences of anger…than the circumstances that aroused them in us?” — Marcus Aurelius

1. Maintain Peace by Releasing Control Impulses

The first principle of anger control in Stoicism is to stop being a control freak.

Separate what you control from what you do not by asking yourself, “Was it something I had control over?”

Your answer will make you see that you were expecting others to think and act in certain ways, while you had no control over their thoughts or actions.

And by getting angry, you were only trying to influence something in vain, which wasn’t yours to meddle with.

They may have been in situations where they could not meet your expectations or carry out your explicit instructions.

Your anger will subside once you grasp the nuances of their situation and respect their free will.

Then ask yourself, “What can I control right now?”

It will help you decide what to focus on, and work toward a solution for your problem.

2. Quick Damage Control by Stopping Angry Impulses

The second principle was to act fast to manage your anger.

The Stoics recognized that anger grows stronger the longer it clings to a person.

And the more intense the rage, the more damaging its repercussions are for both the target and the angry person.

To a Stoic, anger is like being bitten by a snake – the poison enters and takes hold of you, making you feel like you’re in pain; when in reality, the pain has not yet begun.

The key is to cut it while there is still time, long before our anger spirals out of control and makes us regret the consequences.

By the way, regrets are a sign that we must make better judgments in the future. They indicate we have not done what we should have, or done what we should not have.

Actually, living a life of “No Regrets” is such a terrible idea that you may not have realized.

6 Stoic Strategies to Control Anger

The Stoics were interested in how people’s emotions affect their behavior.

They felt that anger is a natural but unhealthy emotion. It hurts our behavior and may lead to destructive activities.

Here are some of the most prominent Stoic principles to control anger:

1. Anger Control Through Self-Awareness

Anger is a state of temporary insanity.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, a renowned Stoic philosopher who served as Emperor Nero’s counsel, said:

“Anger is a temporary madness and that even when justified, we should never act based on it because it affects our sanity.”

The quote “Anger is like a short madness” is attributed to Horace, a Greek philosopher who lived in the 4th century BCE.

Psychology shows when we are angry, we see things negatively and often irrationally. The longer we are angry, the more of this effect (called cognitive distortion) we experience.

So, being aware when we are starting to get angry is the first stage of anger control. The longer the anger, the harder it gets to control.

“The best plan is to reject straightway the first incentives to anger, to resist its very beginnings, and to take care not to be betrayed into it: for if once it begins to carry us away, it is hard to get back again into a healthy condition.”

— Seneca, in his essay On Anger

We all have different capacities of self-awareness. We can sense when someone is losing their calm. But it is hard to notice the anger that is originating and building within us. It takes a long time for us to become consciously aware of our rage.

There are indicators to help us detect anger early on. Rusticus, Stoic mentor to Marcus Aurelius, would spot his pupil’s latent angry impulses and tell him to take note.

Notice the physical cues, like stiff shoulders, tightness of the chest, rapid heartbeat, sweating, or shaking. Identify internal signs, like vengeful or baneful thoughts arising.

Pay attention to inner clues. For example, identify if your boredom or irritation in a situation is actually causing a wave of anger to rise inside.

2. Anger Control Through Contemplation

Anger is ugly. Seneca, quoting the Roman philosopher Quintus the Elder, observed:

It has often been useful for angry people to look in a mirror… its ugliness is so extreme, as it seeps through bones and flesh and so many things in its path; what would it look like if laid bare?

When angry, contemplating the possible consequences of your actions can help reduce your anger.

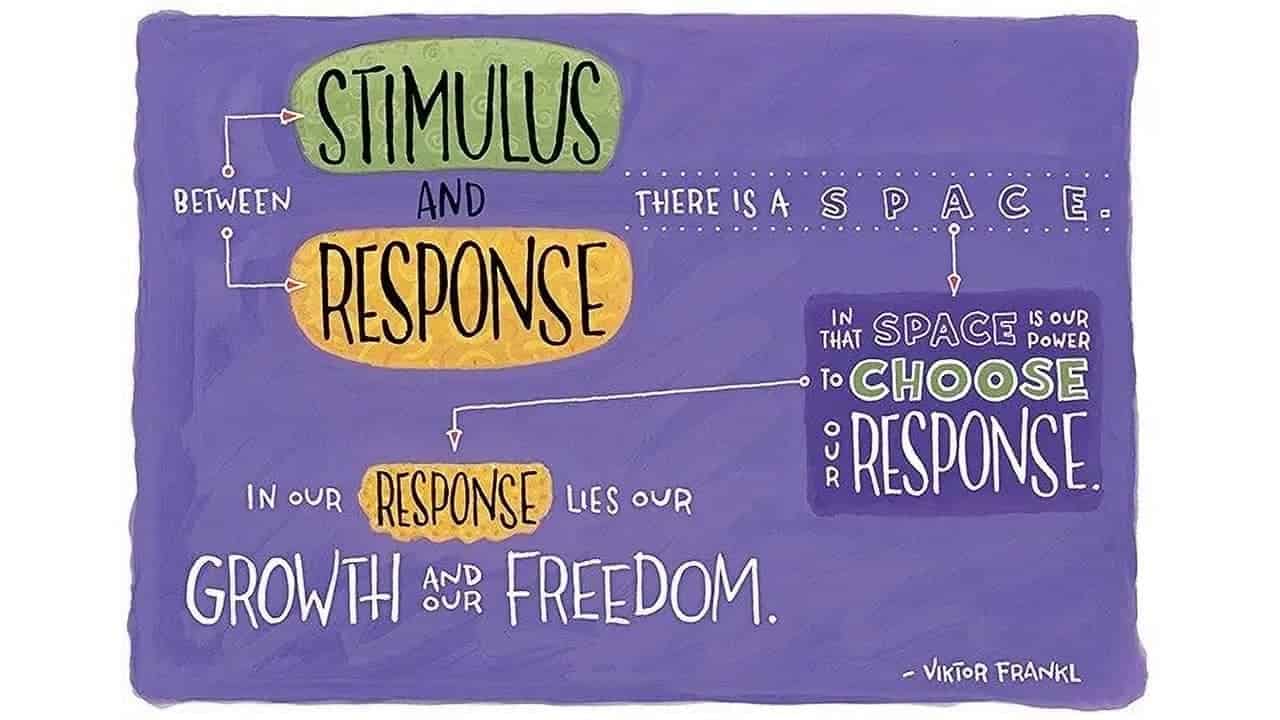

The simplest way to do it is to create a delay between an angry stimulus and your response to it. And use that delay to ponder the situation.

In contemplating our anger, we take a step back and look objectively at the anger-provoking situation. It makes us realize that nothing external is good or bad, but it is our beliefs and judgments that make them such.

Marcus Aurelius practiced the separation of thoughts from external reality. This helped him to avoid reacting with anger when people around him acted irrationally.

Epictetus said that when you’re having an angry thought, tell that thought:

“You’re just an impression. You’re not the thing you claim to represent.”

He asked you to speak to your angry thought as if it were a living person outside you.

The modern science of CBT calls it self-distancing or psychological distancing.

When you talk to yourself in the third person, like “Sandy is angry. Why is Sandy so angry?”, for example, it reduces your reactivity.

A recent study confirms that this strategy is indeed effective in reducing anger.

The … study supports the idea that self-distancing buffers negative affect and anger.

— Michel-Kröhler, Kaurin, et al., 2021

The Stoic response to insult is to pause and consider what has happened before anger overpowers your rational thinking.

Taking a pause when you get angry can help you to see whether your anger is justified or not.

- If you find that your anger is justified, then you should take steps to remedy the situation.

- If your anger isn’t justified, then you should try to put yourself in that other person’s shoes and understand where they’re coming from (develop empathy for them).

- If it isn’t, then you should try to let go of anger before it builds up and makes things worse for yourself or others.

The Stoics also had a way to contemplate seeing things from a distance, called The View From Above.

When we see ourselves from above, we regard ourselves as detached from the world around us.

This exercise also distances us from our worries and fears, letting us see our issues more clearly and less emotionally. It helps us understand the root causes of our problems and find their solutions.

The Stoics also contemplated the troubles that their oppressors were going through.

So, if you feel like someone is giving you a hard time, remember that everyone faces challenges, and it’s how we overcome these challenges that define us. Tell yourself that they owe you nothing, yet they are trying their best to please you.

When you are offended at any man’s fault, turn to yourself and study your own failings. Then you will forget your anger. — Epictetus

3. Anger Control Through Dichotomy of Control

Anger is a natural process that helps us understand and deal with unfair or undesirable situations.

But when anger is uncontrolled, it becomes unhealthy and destructive. Some people may even go into unconsciousness when they become highly enraged, and their heart rate rises to dangerously high levels.

The Dichotomy of Control is a Stoic principle that encourages us to focus on the things we can control and not worry about the things we cannot.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus said,

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. — Epictetus

If you focus on what you can control, the things you cannot control will take care of themselves. You cannot control other people’s words, thoughts, or behavior.

So, stop trying to control them, and you will find your calm.

Moreover, the Stoics thought that we are not so much disturbed by what happens to us as we are by our thoughts about what happens to us. It is the judgments about events that torment us, not the events themselves.

If a person gave your body to any stranger he met on his way, you would certainly be angry. And do you feel no shame in handing over your own mind to be confused and mystified? — Epictetus

4. Anger Control Through Negative Visualization

Premeditatio Malorum, or negative visualization, is a doctrine of Latin origin that translates as the “forethought of evils.”

Premeditatio Malorum is, in one way, the Stoic approach to risk management. Let’s see how.

The Stoics saw life as subject to unpredictable and uncontrollable events, both bad and good. They believed that it was impossible to tell if what has not yet happened will be good or bad.

They saw the human mind as so fragile that it would be better for the person to prevent a disaster, even if it cannot be known if that will lead to better or worse outcomes.

So, the Stoics imagined themselves in various states of adversity and practiced behaving justly in such situations. This premeditation of adversities reduced the mental load and negative impact of the actual adverse events when they were to occur.

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own — not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. And so none of them can hurt me. No one can implicate me in ugliness. Nor can I feel angry at my relative, or hate him. We were born to work together like feet, hands, and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower. To obstruct each other is unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are obstructions.”

— Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius understands he will face opposition from those he will meet later in the day. By mentally preparing ahead of time, he is better able to hold his angry reactions in check when the challenges arrive.

If you rehearse how you should respond to an insult, then when someone insults you, you will find it easier to react rationally rather than angrily. Seneca reminds us to be prepared for trouble even when things are going well.

“Everything might happen; anticipate everything. Even in good, there is something rather unsavory. Human nature contains treacherous thoughts, ungrateful ones, greedy and wicked ones. … Always suppose that something offensive to you is going to arise.”

— Seneca

5. Anger Control Through Mindfulness

Anger is a normal human emotion, but it should not be expressed aggressively or violently. Mindfulness can help people control their anger by visualizing their anger as a large wave that they can ride out, rather than trying to push it away or hold on to it.

Mindfulness is the practice of being aware of the present moment, without judgment. It is a way of letting go of unhelpful thoughts and judgments. [Get this 7-Step Guide To Mindfulness.]

The Stoics popularized the concept of mindfulness through the ancient Greek and Roman world, which they used to control their anger. Stoic mindfulness is explicitly analytical.

Be not swept off your feet, I beseech you, by the vividness of the impression, but say “Wait for me a little, O impression; allow me to see who you are, and what you are the impression of; allow me to put you to the test.”

And after that, do not suffer it to lead you on by picturing what will follow. Otherwise, it will take possession of you and go off with you wherever it will.

And if you form the habit of taking such exercises, you will see what mighty shoulders you develop, what sinews, what vigour. — Epictetus

With mindfulness, we can break our habit of reacting with anger, frustration, or resentment to any event that we judge as demeaning or humiliating to us.

The first step: Don’t be anxious. Nature controls it all. And before long you’ll be no one, nowhere—like Hadrian, like Augustus. The second step: Concentrate on what you have to do. Fix your eyes on it. Remind yourself that your task is to be a good human being; remind yourself what nature demands of people. Then do it, without hesitation, and speak the truth as you see it. But with kindness. With humility. Without hypocrisy. ― Marcus Aurelius

6. Anger Control Through Acceptance

Stoic acceptance implies we must enjoy and appreciate this journey called life, or else we shall be dragged along its crests and troughs.

Our fighting reality and resisting the things we can’t change only makes us angry with the universe and unhappy with our lives.

The Stoic masters felt that angry people blame others, wish that things were otherwise, resent life’s ups and downs, and despise the gods.

The way to inner peace is to accept external events and other people as things bound to happen.

Seneca puts it succinctly:

A wise man is content with his lot, whatever it may be, without wishing for what he has not. ― Seneca

The following exercise that Seneca suggests is negative visualization, but when practiced, it is also an exercise in acceptance of the present and the future unknown.

Set aside a certain number of days during which you shall be content with the scantiest and cheapest fare, with coarse and rough dress, saying to yourself the while, ‘Is this the condition that I feared? — Seneca

Marcus suggests that we accept whatever life we have left and spend our days doing good.

Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life’s books each day… The one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time. — Marcus Aurelius

FAQs

1. What do the Stoics believe about anger?

The Stoics hold that our anger is not because of another person’s behavior, but due to our opinion of their behavior.

They feel that anger is a justified offense rather than an impulsive action, and angry acts are driven by a desire to repay suffering. And that anger is a destructive emotion that we must control and eliminate.

“Anger, for the Stoics, is not an impulsive, instinctive reaction. It is, rather, the cognitive assent that such initial reactions to the offending action or words are, in fact, justified.”

— Massimo Pigliucci, Professor of Philosophy at the City College of New York, Author of many books on Stoicism

Anger is not something to be ashamed of. Everyone feels angry at some point in their lives, but the Stoics believed that it was important for people to control their anger and not let it control them.

2. What did Seneca say on anger?

Anger, if not restrained, is frequently more hurtful to us than the injury that provokes it. — Lucius Annaeus Seneca

Seneca hed that anger is a temporary state of madness. He believed that although “other vices affect our judgment, anger affects our sanity.”

So, he said, even when your anger seems justified, you should never act on it.

Anger is a destructive emotion that can harm not both the angry person and those around them. In Seneca’s words, anger “makes us deaf to reason.” He says anger blinds us from logic and can lead to violence if not controlled early.

The greatest remedy for anger is delay. — Seneca

3. What did Epictetus say on anger?

So, when someone arouses your anger, know that it’s really your own opinion fueling it. Instead, make it your first response not to be carried away by such impressions, for with time and distance self-mastery is more easily achieved. — Epictetus

Epictetus was a Stoic philosopher who was born as a slave and then freed by his master. As a philosopher, he believed that the only thing in our power to control is our thoughts.

Epictetus’s philosophy on anger can be summarized in his quote,

It is not the things themselves that trouble us, but our judgments about them. — Epictetus

In other words, it’s not the event that upsets us; it’s how we interpret it and label it.

Epictetus admonished his students this way:

Remember that it is we who torment, we who make difficulties for ourselves – that is, our opinions do. What, for instance, does it mean to be insulted? Stand by a rock and insult it, and what have you accomplished? If someone responds to insult like a rock, what has the abuser gained with his invective?

No one can hurt you without your permission. If we choose to disregard the insulting words and actions of others, we cannot get hurt.

When someone throws you an insult in a foreign language, do you feel hurt? No. You can similarly drop the meaning from the hurtful words thrown at you, and prevent yourself from getting hurt by them.

Another person will not hurt you without your cooperation. You are hurt the moment you believe yourself to be. — Epictetus

4. What did Marcus Aurelius say on anger?

Keep this thought handy when you feel a fit of rage coming on— it isn’t manly to be enraged. Rather, gentleness and civility are more human, and therefore manlier. A real man doesn’t give way to anger and discontent, and such a person has strength, courage, and endurance— unlike the angry and complaining. The nearer a man comes to a calm mind, the closer he is to strength. — Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius was a Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD. He is known as a philosopher-king, and his writings are still studied today.

Marcus Aurelius said that it is much more profitable to be patient than to be angry.

You shouldn’t give circumstances the power to rouse anger, for they don’t care at all. — Marcus Aurelius

And this,

How much more harmful are the consequences of anger and grief than the circumstances that aroused them in us! — Marcus Aurelius

5. What did Musonius Rufus say on anger?

If we were to measure what is good by how much pleasure it brings, nothing would be better than self-control- if we were to measure what is to be avoided by its pain, nothing would be more painful than lack of self-control. ― Musonius Rufus,

Musonius Rufus was a Stoic philosopher who believed that anger is a destructive and irrational emotion. It will lead to more problems and not solve anything.

He believed that anger would only cause more problems and wouldn’t solve anything.

To accept injury without a spirit of savage resentment-to show ourselves merciful toward those who wrong us-being a source of good hope to them-is characteristic of a benevolent and civilized way of life. ― Musonius Rufus

6. What did Zeno of Citium say on anger?

Man conquers the world by conquering himself. ― Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium was a well-known philosopher before he founded Stoicism. He saw anger as an irrational emotion with far-reaching consequences that we should eliminate from our lives.

Zeno gave the idea that we may avoid anger if we listen to the other person in silence.

The reason why we have two ears and only one mouth is that we may listen the more and talk the less. ― Zeno

A Modern Stoic’s Guide To Anger Control

Massimo Pigliucci, an academic philosopher, suggests the following on anger management:

- Preemptive meditation entails thinking about what situations make you angry and deciding how to deal with them ahead of time.

- Check for signs of anger as soon as you notice them. Don’t put it off much longer, or it will spiral out of control.

- As much as possible, associate with calm people; avoid irritable or angry people. Moods are contagious.

- Play a musical instrument or indulge in whatever activity you find relaxing. A calm mind does not become enraged.

- Seek situations with attractive, rather than irritating, colors. Manipulation of external circumstances can have an impact on our moods.

- Don’t engage in arguments when you’re weary because you’ll be more prone to irritability, which can quickly build into fury.

- For the same reason, don’t start a conversation when you’re thirsty or hungry.

- Use self-deprecating humor as our major defense against the Universe’s unpredictability and the predictable cruelty of certain of our fellow humans.

- Practice cognitive distancing – what Seneca refers to as ‘delaying’ your response – by going for a walk or retiring to the restroom, or doing anything else that will give you a break from a stressful situation.

- Change your body to change your mind: purposefully slow down your steps, lower the tone of your voice, and impose a calm demeanor on your body.

Origins of Stoicism

After Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, various philosophical schools emerged to help people handle the stress of constant geopolitical conflicts. These Hellenistic thinkers shifted the focus of philosophy from a general understanding of the universe to one of individual life and an “art of life”.

They aimed to figure out how to achieve eudaimonia, or happiness and satisfaction in life. Stoicism and Epicureanism were the two most well-known of these.

Around 300 BCE, Zeno of Citium founded Stoicism in Athens. Its central tenet was that Virtue is enough to make our lives happy and fulfilling. Virtue had four cardinal ideals: courage, justice, temperance, and wisdom.

Stoics believed people should live according to the natural world. They felt the universe is perfect, and so we should use it as a model for how we should behave.

Three of the most famous Stoics are Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius.

Final Words

Stoicism emphasizes self-control and living a life free of worldly vanity.

The Stoics forego emotional outbursts and life’s comforts in favor of a modest, virtuous, reason-based lifestyle. They aim to live a life of contentment with the things they own and with the way the universe works.

The Stoics knew that to calm down an angry mind, they must delay in reacting to an angry event, imagine the future consequences of their thoughts and actions, and recognize that their anger is irrational and unjustified.

“The nearer a man comes to a calm mind, the closer he is to strength.”

— Marcus Aurelius

One final counsel: when someone makes you angry, recognize that they are not all that different from you. Reflecting on their nature as humans may fill your heart with empathy and compassion, and melt away your anger.

√ Also Read: Stoicism In A Nutshell

√ If you liked it, please spread the word.

» You deserve happiness! Choosing therapy could be your best decision.

...

• Disclosure: Buying via our links earns us a small commission.