Reading time: 15 minutes

Trust is a choice. Breaking of trust is also a choice.Trust makes relationships work, though it has limits. You don’t need to share with your partner every office secret or personal password to prove your loyalty.

Even if your friends and coworkers rate you as trustworthy, you may still cheat on your partner.

When you cheat, the truth is, you made that choice.

Even if you blame it on your relationship discontent.

25% of the reasons why some people cheat can be traced back to low satisfaction or low intimacy in the relationship. (Thomson, 1983).

So before you can even start repairing the damage, you need to own up to it. Your infidelity is a trauma on your partner, own your role first.

With the internet, cheating is cheap and easy. Now it is also a business that makes money.

Cheating is when someone channels their sexual energy or emotional support to their non-partner (Gregory Kushnick, NYC Psychologist).

8 Ways To Rebuild Trust After Cheating: Clues From Research

Cheating is a violation of trust, often caused by unfulfilled needs. Rebuilding trust is about meeting those needs after saying sorry and promising not to repeat it.

Here are four short-term and four long-term strategies for rebuilding trust after cheating, backed by research:

1. Confess And Give A Verbal Explanation.

If you’re the cheater, tell them the details about the entire incident. Give them a full account and offer your explanations at each stage.

Acknowledge you have cheated on them and take ownership and responsibility for the act.

A survey of 441 Americans revealed the following data:

- 47% of respondents admitted to their infidelity within a week, 26% within a month, and 25.7% after six months or longer.

- Only 29.2% of married respondents admitted their infidelity within a week, and 22.9% opened up about it to their spouses within a month.

- 46.9% of men admitted their infidelity within a week, and 48% of women did the same.

Explanations that were more specific and detailed regarding the circumstances of the violation were more successful than those that were less specific but delivered in a more sincere manner.

These efforts address the cheating directly and make a silent plea to “move on” in the relationship.

Excuses: Often, explanations include excuses, which is unhelpful.

When you make an excuse, you give up ownership of a problem or solution. An excuse is a veiled justification for the vile act, and tries to absolve you of responsibility, and lets you avoid taking corrective action.

Don’t try to manipulate your partner by adding excuses to your accounts.

Beware what Benjamin Franklin said,

“Do not ruin an apology with an excuse.”

People often do things that turn out badly despite “good intentions” or “no such (bad) intentions,” but that is hardly a good argument supporting the act of cheating.

2. Offer A Sincere Apology.

An apology is a statement that explains the violation (like cheating) and also includes “emotional content” such as the intent behind the violation, regret, and promise of changed behavior.

A good apology has at least four parts:

- Expressing sincere regret. “I’m sorry.”

- Assuming personal responsibility for the act. “It was my fault/I was wrong.”

- Promise of corrective action to the current crisis. “This is what I’ll do as a remedy.”

- Requests a pardon for the act. “Please forgive me for the harm I caused.”

The third part above is possibly the most crucial part. If the cheater does not tell their partner how they are going to take steps to make things right, then the apology remains hollow.

Apologies are more successful when they are prompt and include an expression of regret, an explanation for the violation, an admission of responsibility, a declaration of repentance, an offer of repair, and a request for forgiveness.

However, according to Fehr and Gelfand (2010), one of the key drivers of whether an apology will work is how the particular recipient perceives, processes, and responds to that information.

For example, if a person is autonomous and independent, any form of apology is less effective than compensation.

3. Propose A Compensation.

Proposing compensation will often soften the victim-partner’s stance towards you and make them more willing to forgive.

Farrell & Rabin, 1996, argue that explanations and apologies are no more than “cheap talk” and that only direct compensation is effective.

In the case of cheating, for example, it could be a “symbolic” repayment. It could be giving direct compensation or tangible benefits to the victim as the cost of cheating, with or without any verbal confession or statement.

Some examples:

- I may not be able to undo the betrayal of your trust, but I commit to devoting two hours every weekend to any of your work.

- We can book a trip to your desired destination.

- We might go to an expensive dinner at your favorite restaurant.

- I’ll buy you that new phone.

Although this is debatable, the compensation could try to “match” the severity of the violation to be more effective. A new gadget may balance a one-night stand, while an extended affair might require a week-long vacation in an exotic place and unchecked shopping.

4. Deny The Act. Disown The Guilt.

Denial is a statement that explicitly declares an allegation to be untrue and hence admits no regret.

This strategy involves categorically denying that cheating ever happened. It allows the cheater to escape being accused or to suffer guilt.

A denial seeds the victim’s mind with the benefit of the doubt and is especially effective if the cause of the cheating cannot be proven. Like, “It never happened! Why do you even think I needed to do it?”

The moral drawback of denial is that it implies there is no need to correct one’s behavior, which may increase the cheater’s chances of future adulterous behavior. Denials can turn a minor offender into a major culprit.

One of the most widely quoted conclusions from studies is that when a violation is based on integrity, denial is more effective than an apology to repair the trust.

So, denial is often an effective strategy if the victim calls the cheater’s personal integrity, honesty, and character into question. In such cases, denial is more successful than apologies like “Sorry, I knew I was doing something wrong,” or “Sorry. I lied to you.”

5. Reframe The Incident

Reframing can be an effective trust repair tactic in cases of cheating. It attempts to shift the blame, explain away the unfaithfulness, and minimize the perception of damage.

Reframing can convince our victim-partner to tone down and readjust their expectations from us. This downplays their perception that a trust violation happened in the first place, because the expectations were so low.

Like, “You always knew how wild I was in my younger days,” or “You now know what I was missing in our relationship.”

Since unmet expectations are often the root of trust violation, reframing might include reframing the offender’s and victim’s expectations, connection, context, or acts and cause attributions.

Empathy can heal fractured trust and broken relationships. Reframing a problem can help with perspective-taking—a form of empathy in which we imagine another person’s ideas or feelings from that person’s point of view. It can help with trust rebuilding (Williams, 2012).

An example of empathetic reframing could be,

“Let’s handle this as we two against this disaster, not as we two against each other.”

6. Ask For Forgiveness

Forgiveness is a key aspect of the trust-rebuilding process. It saves a committed relationship and encourages the cheater to break out of his illicit affair, and not repeat the offense.

Forgiveness does not include pardoning, condoning, justifying, excusing, self-denial, or forgetting (Butler et al. 2002).

Most experts consider forgiveness as a personal “coming to terms with” or gaining inner peace over an offense, paired with adopting a kind stance toward the offender and probably (but not necessarily) starting efforts toward relational restoration (Butler et al. 2013).

Some factors that help the victim forgive the cheater:

- apology based on shame or guilt,

- feeling of remorse,

- empathy – perspective-taking and compassion,

- ability to recognize the harm done to the victim-partner

- the determination of both partners to keep the relationship going

According to Maio et al. (2008), forgiveness involves consciously shifting from “negative ideas, feelings, and behaviors toward the transgressor to more positive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.”

Forgiveness indicates that the victim-partner accepts the violation and wishes to start rebuilding the relationship with the offender. It also implies that the wrongdoer has expressed regret and has committed to not repeating their offense (Kramer & Lewicki 2010).

Read this absorbing article on How To Forgive A Cheater And Move On.

7. Be Silent. Maintain Your Silence.

Silence seems to tell the victim-partner we do not care about either the relationship or the consequences of our infidelity to them.

Silent offenders stonewall and do not respond to accusations of violations.

Anecdotally, silence is a common technique used to regain trust after an offense. Silence seems to wait for the storm to pass.

Silence is worse than apologies but better than excuses.

Silence might also let the cheater radiate an impression of hurtfulness or self-righteousness, like “I’m so hurt by the allegations that I am at a loss of words,” or “I will not dignify it with a response.”

For example, the comedian Bill Cosby was accused of many instances of sexual assault, but he remained silent and refused to even address the claims for several months.

In fact, a 2014 NPR headline was Bill Cosby’s Silence On Rape Allegations Makes Huge Media Noise. The Washington Post called it “perhaps the most significant dead air in the history of National Public Radio.”

Silence is helpful when an offender realizes they have broken trust, but they do not want to acknowledge it or deny it.

If they were to confess verbally or compensate for their offense, they will have to face the consequences. And if they were to deny it, then they will have it worse when their denial gets exposed as a lie.

8. Plan And Put In Place New Arrangements

Researchers Lewicki and Brinsfield suggest,

“One longer-term trust repair strategy has been to create new and different structural arrangements between the parties so that the parties bound and limit their future possibilities for subsequent violation.”

Their intended purpose is to change the situation that led to the breach of trust in the first place.

These strategies may include:

- taking a break from each other,

- controlling how they interact,

- creating treaties or contracts that specify the actual consequences in case of a future violation,

- proposing self-imposed penalties if the cheater repeats the offense are examples of these strategies.

Rearrangements help set up relationship boundaries and reduce the likelihood of the repetition of cheating. According to the data, only 10% of affairs are longer than 6 months.

Cheating can be defined as a behavior that violates an implicit or explicit pact or understanding between a couple in a relationship about what activity is and is not permitted.

What classifies as cheating depends on what a couple jointly defines as a deviation from their mutually set boundaries, as it is unique to every couple. Cheating can be carried out through physical, emotional, or digital means.

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) For Marital Infidelity

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) is a type of couples therapy. It holds that healthy relationships are based on strong, secure emotional bonds.

Infidelity can severely damage the attachment bonds between partners. EFT provides a structured approach to help couples through this difficult situation. The key aspects are:

- Acknowledging the pain: Both partners openly express their feelings of hurt, betrayal, and grief caused by the infidelity. This allows the couple to validate each other’s emotions.

- Expressing remorse and regret: The partner who was unfaithful is guided to take responsibility and sincerely apologize, expressing remorse and regret for their actions.

- Repairing the attachment bond: Focus on rebuilding trust and repairing the emotional connection. This involves creating a safe space for vulnerable conversations, understanding each other’s attachment needs, and developing new, healthier patterns of interaction.

The goal of EFT is to help the couple move from a place of disconnection and distrust to one of renewed closeness, empathy, and commitment.

How Frequent Is Cheating

Roughly 26% to 50% of all married couples in America experience infidelity at some point (The Evolution Of Desire, David M. Buss, 2016).

Interestingly, there is some truth to this saying: ‘Once A Cheater, Always A Cheater.’

Studies show people who cheat in a new relationship often have a history of doing so with a previous partner:

- A study published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior found that those who cheated once are 3 times more likely to engage in infidelity again (serial infidelity).

- An estimate from the journal Marriage and Divorce concludes that 70% of married Americans cheat at least once in their marriage.

- According to LA Intelligence Detective Agency, 30 to 60% of married couples will cheat at least once in the marriage. 74% of men and 68% of women admit they would cheat if they were sure that they would never get caught. 60% of affairs start with close friends or coworkers.

- 33% to 40% of affairs happen with a friend, and 29% to 31% happen with a coworker. This 2021 study of over 2,000 employees revealed that 66 percent of respondents reported that they either witnessed cheating or cheated personally on work trips.

- Both women and men cheat more during their middle ages, with the 30-39 age group having the highest rate of infidelity.

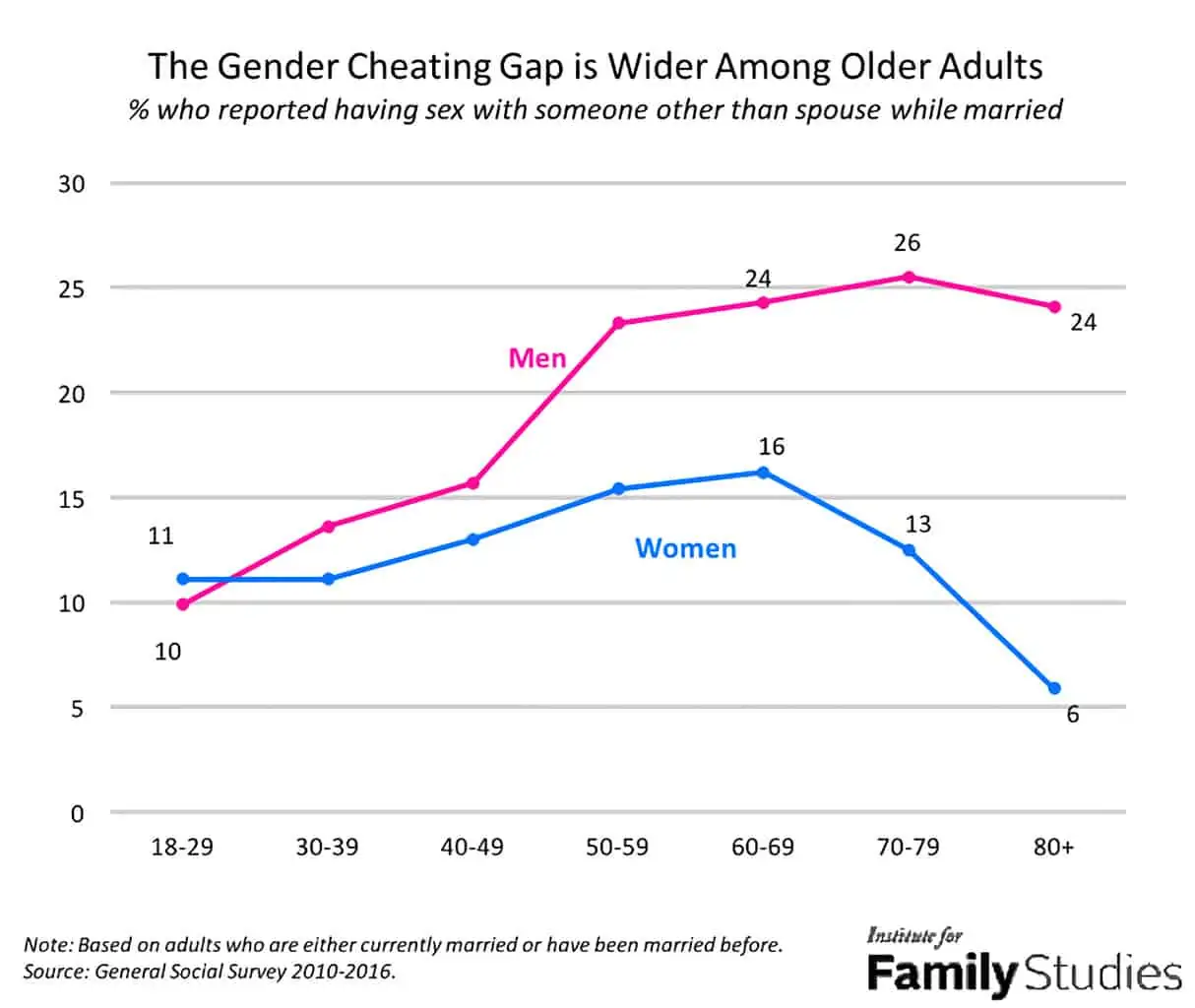

- The rate of infidelity among men steadily increases with age, peaking in the 70-79 age group. Infidelity rates among women rise with age until the 60-69 age group, then decline sharply.

Who Cheats More

Men tend to cheat more.

That said, the infidelity gap between the genders is closing.

According to the United States General Social Survey, 20% of men cheat, compared to 13% of women. The same survey threw the following interesting data:

- Over 90% of Americans consider infidelity immoral.

- Around 30% to 40% of Americans cheat on their partners.

- Less than 3% of American adults believe it is not wrong to engage in extramarital sex.

Why People Cheat

Four key motivations for cheating are:

- low self-esteem,

- a lack of love in the primary relationship,

- unhappiness, and

- sexual dissatisfaction.

Other reported reasons are — anger, low commitment to one’s partner, need for variety, neglect, high sexual desire, and situation.

- Of men, 40% said they cheated because they wanted more variety in sex; 44% said they cheated because they wanted more sex.

- Among women, 33% said they cheated because they wanted to feel desired; 50% said they wanted to feel an emotional connection; 11% did it out of revenge.

The Kinsey Institute found that “lower relationship happiness” accounted for 72% of men cheaters and 62% of women cheaters. And “lower sexual satisfaction” accounted for 69% of men cheaters and 40% of women cheaters.

A 2020 survey by Gleeden found almost 77% of Indian women who cheated on their spouses said they did so because their marriage had become monotonous.

Men and women also cheat in different ways:

- Men more likely engage in one-night stands

- Women more often seek emotional connections

How People React To Cheating

The Infidelity Imagination hypothesis says:

- Men are more upset by sexual infidelity, but

- Women elicit a stronger reaction to emotional infidelity.

- Women are more distressed than men when their partners are unfaithful with a highly attractive paramour.

Evolutionary psychologist Buss, 2018, feels jealousy is an evolved defense against relationship threats (infidelity) for women and men.

- Men are more likely to imagine explicit sexual details than women (Rupp & Wallen, 2008)

- Women are more likely to imagine emotional or romantic stories (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995)

What Helps Trust-Building After Cheating

Trust is a “social glue.” When broken, rebuilding it will need, besides apologizing, negotiating the unmet needs in the relationship.

Still, repaired trust may not be as good as an unbroken one.

Researchers assume “repaired” trust never reverts to its original “pristine” level, and some damage remains after betrayal (Lewicki, 1998).

- From the victim’s point, there is an enormous shift in the way the victim thinks about the relationship and feels toward the offender.

- From the violator’s point, it might predict that one instance of opportunistic cheating may lead to an increased frequency of further violations.

Trust has three components, as research suggests (Rousseau et al., 1998):

- Cognitive — beliefs and expectations

- Affective — emotional connectivity

- Behavioral — actual behavior

All three play their roles in building trust again after cheating.

- “Sorry, I made a mistake” is more easily accepted than “Sorry, I knew that I was doing wrong.”

- The first one shows a failure of competence. The second one shows a breakage of integrity.

- We seem to repair relationships less easily with the willful violator.

If the cheated-upon person believes a lack of the ability to resist temptation drove the adultery, and she has had a good past relationship with the cheater, she is more willing to reconcile.

But if the victim believes the cheating was intentional and the cheater was proactive, and she remembers their tiffs about his “roving eyes,” she is less ready to patch up.

Further Reading:

- The Repair of Trust, Academy of Management Review, Peter H. Kim, Kurt T. Dirks and Cecily D. Cooper, Vol. 34, No. 3 (July 2009).

- Trust Repair, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, Roy J. Lewicki and Chad Brinsfield, Vol. 4:287-313 (March 2017).

- A cognitive process model of trust repair, International Journal of Conflict Management, Edward C. Tomlinson , Christopher A. Nelson , Luke A. Langlinais, Vol. 32 No. 2 (Oct 2020).

Final Words

By definition, trust is “the extent to which a person is confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the words, actions and decisions of another” (McAllister 1995).

After cheating, we can rebuild trust if we return to the original principles we built it on.

√ Also Read: How To Set These Six Boundaries In Every Relationship

√ Please spread the word if you found this helpful.

• Our Story!